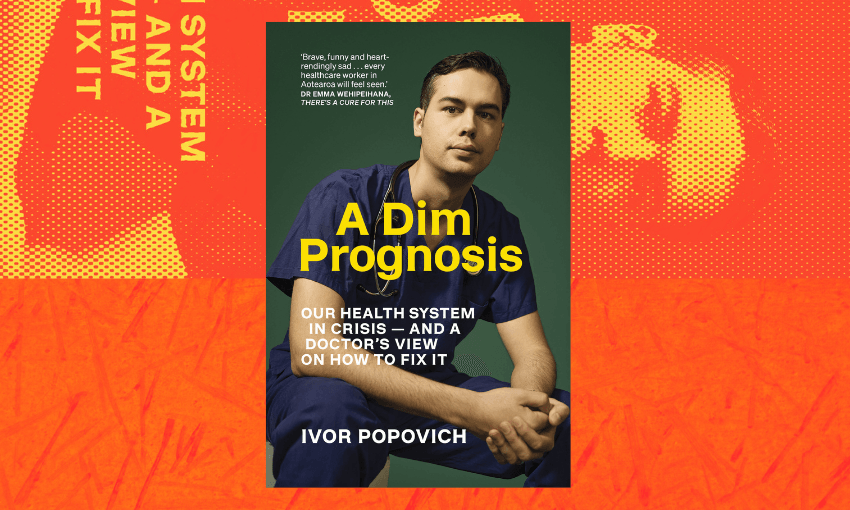

In this excerpt from his memoir, A Dim Prognosis: Why our health system is on its knees, Ivor Popovich gives an example of why we need more nurses; and why their working conditions are less than ideal.

Some years ago I was on a night shift looking after a patient who had just had open heart surgery. Having someone stop then restart your heart is a big deal, and patients can get really sick before they get better. As a result, these patients often end up with tubes and lines sticking out of every orifice.

One of these is a catheter that runs through the jugular vein in your neck and sits inside your heart, where it measures the amount of blood your heart pumps around your body per minute. This is your cardiac output. In an average healthy human it is about 5 litres per minute but it varies a lot, depending on how much blood flow your body needs. When you exercise, your heart can pump more than 20 litres per minute.

Halfway through my shift I was walking around, checking up on patients. The ICU can be strangely peaceful at night, the gentle rhythmic hiss of a roomful of ventilators pushing air in and out soothing your nerves. The patients were all sedated and asleep, which meant there was no chance of a confused patient running around butt-naked (which was not uncommon in the ICU at night). One of my friends once told me that the first time he questioned his career choice was when he was about to inject a sedative into the butt cheek of a naked man who was pinned down by four security guards after spending half an hour being chased around the hospital.

Ms Jones was doing well after her surgery. Her numbers all seemed satisfactory, except her cardiac out-put was a little low, at 3.5 litres per minute. I frowned. This wasn’t quite good enough, and the supervising specialist wouldn’t be happy with me if I let it stay at that all night. I prescribed her half a litre of intravenous fluids. Hopefully this would fill up the heart more, allowing it to pump more blood around. I came back half an hour later, expecting the problem to have gone away. Instead, the cardiac output now read 3.4 litres per minute. I prescribed another half-litre of fluid. The patient’s blood pressure went up, but still the cardiac output wouldn’t budge. Now I was getting irritated. Why wasn’t my therapy doing what it was supposed to do? Time for something more heavy-hitting. I prescribed a drug infusion to stimulate the heart muscle to squeeze harder.

Within minutes the cardiac output had increased to 4.5 litres per minute. Quite pleased with myself, I went for a rest. In the morning the specialist came around, and tore me a new one.

“What the fuck did you prescribe that for?”

“Well, the . . . the car . . . cardiac output was low,” I stammered.

“Are you a doctor or just someone who reads numbers?”

I didn’t understand. I had just wanted to make the patient better. Why was I in trouble?

He looked at me and shook his head like a disappointed dad. “It doesn’t matter what the cardiac output is, only whether it is enough for the needs of the patient. Whatever cardiac output you have right now is enough for you, but it wouldn’t be enough for someone running a marathon. Did Ms Jones, a sedated patient not doing any activity, have any signs that 3.5 was too low for her? Cold arms and legs, low urine output, was she unstable?”

“No.”

The lesson: absolute numbers are not the full picture. And so it is with numbers of nurses. It matters not how many we’ve employed; it only matters whether we have enough to meet the needs of the system. The answer, for anyone who has eyes and ears and has set foot in a hospital lately, is no.

In 2024 a multimillion-dollar extension was built in a major hospital, designed to increase elective surgery capacity, with thousands of extra surgeries promised. It opened six months late, and for even longer was bereft of patients — there were not enough nurses to staff it. Operating theatre staff as well as nurses were simply transplanted from the old building to the new. So much for extra capacity.

Nurses go on maternity leave, they retire, they resign, and the gaps they leave go unfilled. Local hospital managers no longer have the power to advertise or fill gaps. They have to go up the chain for approval. But of course we are “over-budget”, so nothing happens. Numbers alone do not reflect experience. There is a huge difference between a pool of battle-hardened veterans and a pool of rookies. The loss of experienced and skilled nurses over the years has not gone unnoticed by the medical profession. One contributing problem, aside from overwork, is the erosion of nursing independence.

On another of those fateful house officer night shifts early in my career, I had just lain down for a little rest when I got a message on the on-call phone app. “Hi, Doctor, patient’s chest drain suction has been prescribed in mmHg [millimetres of mercury], protocol says it needs to be prescribed in cmH2O [centimetres of water].”

I stared at the message through droopy eyelids, daring it to be a joke. After a few minutes, with no follow-up message of “Haha, gotcha!”, I fired back: “You can google the conversion factor.” It was 1.36. As soon as I shut my eyes, another beep wrenched them open.

“OK, have googled. Is 600 cmH2O of suction correct?”

I tore out of bed so fast I practically teleported down to the ward. In the nurses’ station a nurse was standing waiting for me.

“600 cmH2O of suction?” I said as I filled out the correct prescription on the chest drain protocol. “Are you trying to suck his lungs out of his body? It’s 25!”

He just smiled calmly at me. “OK doc, thanks for coming.”

He took the paper protocol and walked off. I stared after him in incredulity, then started to laugh and shake my head as I realised I’d been played. He knew full well how to convert between the two units. At the end of the day, though, if it wasn’t prescribed on the protocol, it would be him that got in trouble for using his initiative, and the fastest way to get me down there was to seem incompetent.

This is the punitive and suffocating environment that nurses have to work in. The protocols and guidelines and forms that were designed to help, now enslave us all. People worry that not following a protocol to the letter means putting the patient at risk. There are always cases where the standard protocol is not appropriate, and you will not learn to recognise these situations and use your initiative if you always blindly follow the protocol. Nurses’ experience and judgement are being told to take a hike — the mighty protocol rules all.

When the Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner publishes its periodic case findings, nurses are always getting into trouble for this, regardless of whether or not their actions actually made a difference to the outcome of the case. Instead of encouraging independent thinking and problem-solving, our system punishes it. The result is enormous “time rot”, because now the nurse will page me when the patient complains of an itchy bum, because they are afraid to use their own judgement.

A Dim Prognosis: Our health system in crisis – and a doctor’s view on how to fix it by Ivor Popovich (Allen & Unwin NZ) can be purchased from Unity Books.