With a new cause to support, the ice bucket challenge is back. But what are the pitfalls of attempting to raise money through social media?

I was waiting for a friend when I first heard about the ice bucket challenge. “Can you help me with this?” her younger brother asked. I followed him outside, holding a camera while two others poured water over his head. None of us had anything else to do, because we were 14. The year was 2014.

Soon enough, it was my turn. A friend from our cross-country running club posted a video to Facebook of water being poured over her head. She tagged my sister and me. We duly traipsed out to the courtyard carrying a bucket of water filled with ice cubes, and came back inside dripping. I had the faint notion that this challenge was being done by celebrities, and an even vaguer idea that it was to raise money for ALS, a type of motor neuron disease (MND). I had no money to give – I didn’t even have a debit card – and it seemed like all my friends had been tagged already. I never put the video online, and can say with confidence that my efforts made absolutely no impact on people with motor neuron disease.

My vague notion of there being a link between asking people to saturate themselves in frigid water and raising money for a degenerative neurological condition was at least correct. “Started by someone with MND, it’s supposed to give a momentary feeling of what living with MND is like,” says Myrddin Gwynedd, a communications specialist at MND New Zealand. While I personally had no way to give money to the cause in 2014, millions of dollars of donations have been made to the American charity behind the challenge, and the foundation was given US$50m last year, an all-time high.

The social media phenomenon was great for fundraising, Gwynnedd says. “In New Zealand, the ice bucket challenge and the awareness it created have contributed to raising at least $2 million over the past decade. Yet there’s an enduring need for money and research. MND still has no cure and no meaningful treatments. It remains a progressive and fatal condition, and the need for support, awareness and research is as urgent as ever.”

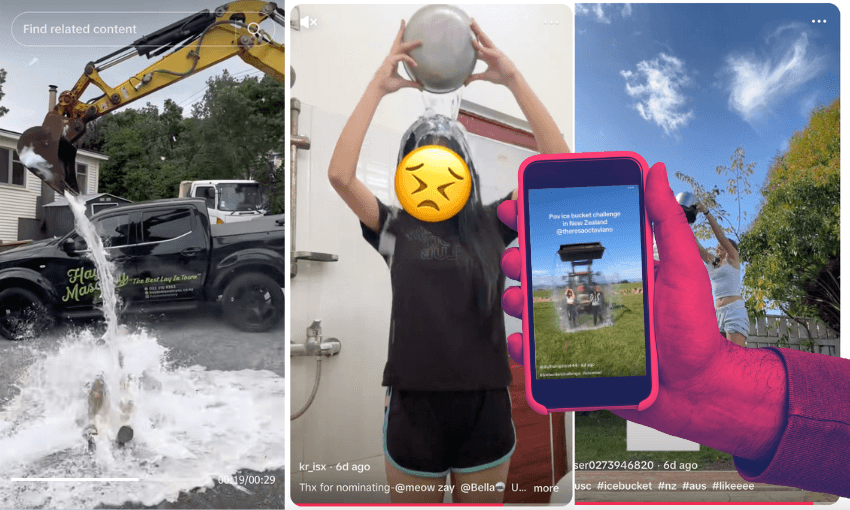

But while it was initially for MND awareness and fundraising – and has been used as a tool by MND organisations around the world since – the challenge has now been repurposed. A group of University of Southern Carolina students in the US are using the challenge to raise money for American mental health charity Active Minds, which has reportedly seen a 922% increase in traffic to its website in recent weeks. No longer focused on the out-of-vogue Facebook, as was the case in 2014, the gushes of cold water are being documented on TikTok instead.

On that platform, it’s easy to find New Zealanders participating in the trend. A person holding the camera squeals as their friend nominates them for the challenge. The Wellington coffee shop/TikTok skit group Kosmos are inundated next to a parked ute. Two young women have a torrent poured on them from a tractor. An AI-generated version of Whangaparāoa College’s principal is swept away in a digital wave.

There are several key elements that made the ice bucket challenge go viral, whether in 2025 or 2014, says Philippa Smith, a digital media consultant who has used the original version as a teaching example for students at AUT. It’s simple to participate in, requiring minimal equipment or expense. It’s pretty fast – compared to, say, raising money by running a half marathon or participating in World Vision’s 40 Hour Challenge. “It answers a need to participate, and a need [for charities] to raise money,” Smith says. That phone cameras and social media accounts were widespread by 2014 helped, too: the challenge became popular because it could be documented, surely contributing to social media companies’ profit margins along the way.

“People like a challenge – particularly when celebrities are involved,” Smith says. In its spectacle, the ice bucket challenge reminds her of the Telethon days of old. “People would ring up and say ‘I’ll donate money if a celebrity does 50 push-ups’, or something like that,” she says. Perhaps tagging a celebrity is its modern equivalent, taking place on the formless expanse of the internet rather than the regimented shapes of a TV studio.

The aspects of the ice bucket challenge that make it appealing can also make it superficial, not engaging substantially with the issues it claims to address – whether that be mental illness or motor neuron disease. Jazz Thornton, a New Zealand mental health advocate, has chosen not to participate in the ice bucket challenge. While the original version of the challenge “created a global conversation about what it was to live with ALS”, she said in a video posted to TikTok this week, “there are other ways I can advocate for mental health.” Instead of tagging people in a video, she suggested something more substantial. “If we’re nominating people, why not check in on three friends, see how they are?”

Smith says the challenge is also imported from the US, and might not be suitable for the New Zealand context. “The message is, if you donate to this organisation, they’ll do more for mental health – but is there a real benefit for New Zealand youth?” Awareness can only go so far: for many people, it’s not awareness of mental illness that is lacking, but access to specialist mental health services.

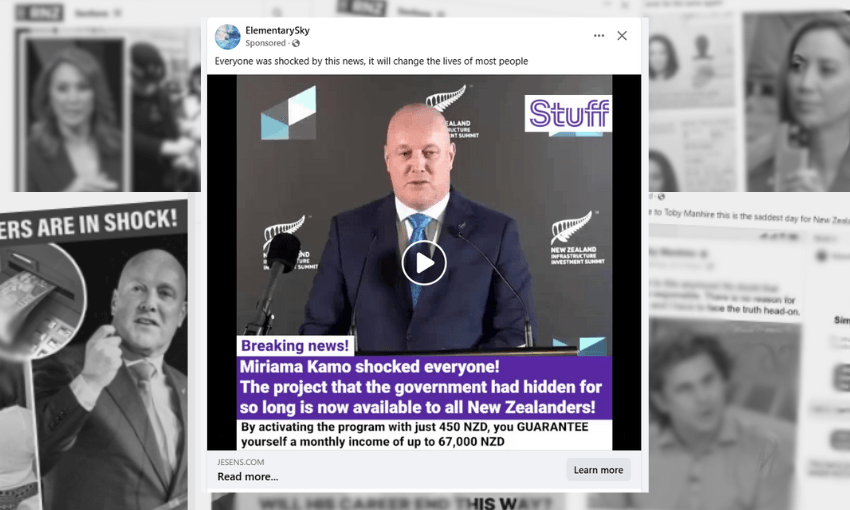

A similar digital effort in 2019 saw Kiwibank offering to give $50,000 to Mike King’s charity Gumboot Friday for every person who added a frame reading “I Am Hope” to their Facebook profile picture – a way for people to give money to charity without having to open their wallets themselves. While many of the frames remain on unused Facebook accounts to this day, the effort is arguably minimal compared to, say, convincing the government to give your charity millions of dollars.

Pouring a bucket of water over yourself or a friend is a pretty harmless activity, Smith points out. Off camera, certainly, wet clothes can be exchanged for dry ones, and the American MND charity has said it has no issue with the original ice bucket challenge being used for a new cause.

“There’s a lot of good intentions – but when it comes to social media, you have to be aware of the bigger context,” Smith says.