The new member’s bill misdirects attention from the systemic drivers of online harm and places the burden of online safety on young people themselves, while the systems that foster harm continue unchecked.

A National MP’s proposal to ban under-16s from social media is being pitched as a bold move to protect young people. But the reality is more complicated and far more concerning. If the National Party is serious about addressing the real harms young people face online, banning users is not the solution. Regulating platforms is.

The Social Media Age-Appropriate Users Bill, a proposed member’s bill led by backbencher Catherine Wedd, would require social media platforms to take “all reasonable steps” to prevent under-16s from creating accounts. Although only a member’s bill yet to be drawn from the biscuit tin, the bill was announced by prime minister Christopher Luxon via X and thereby has the PM’s obvious stamp of approval. The bill echoes Australia’s recently passed Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Act 2024, which imposes significant penalties on platforms that fail to keep children under 16 off their services.

Wedd, like many who support these measures, points to concerns about online bullying, addiction and other inappropriate content. These are real issues. But the bill misdirects attention from the systemic drivers of online harm and places the burden of online safety on young people themselves.

A popular move, but a flawed premise

This policy will likely have the support of parents, similar to the school phone ban – it is a visible, straightforward response to something that feels out of control. And it offers the comfort of doing something in the face of real concern.

However, this kind of ban performs accountability but does not address where the real power lies. Instead, if the aim of the policy is to reduce online harm and increase online safety, then they should consider holding social media companies responsible for the design choices that expose young people to harm.

For instance, according to Netsafe, the phone ban has not eliminated cyberbullying, harassment or image-based sexual abuse for our young people.

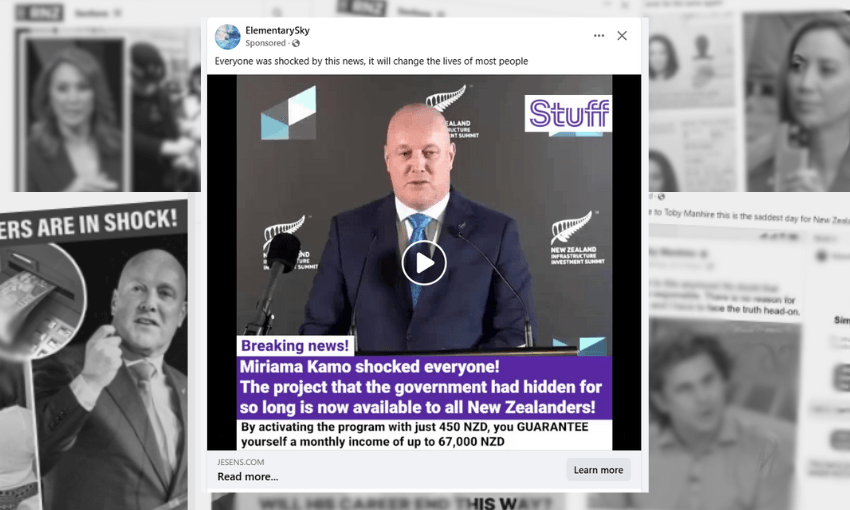

At the heart of the proposal is the assumption that banning teens from social media will protect them. But age-based restrictions are easily circumvented. Young people already know how to create fake birthdates, or create secondary accounts, or use a VPN to bypass restrictions. And even if the verification process becomes more robust through facial recognition, ID uploads, or other forms of intrusive surveillance, it raises significant privacy concerns, especially for minors. Without additional regulatory safeguards, such measures may introduce further ways to harm users’ rights by, for example, normalising digital surveillance.

In practice, this kind of policy will not keep young people off social media. It will just push them into less visible, less regulated corners of the internet and into the very spaces where the risk of harm is often higher.

Furthermore, there is a growing body of research – including my own – showing that online harm is not simply a function of age or access. It is shaped by the design of platforms, the content that is amplified, and the failures of tech companies to moderate harmful material effectively.

Misdiagnosing the problem

Online harm is real. But banning access is a blunt instrument. It does not address the algorithms that push disinformation, misogyny and extremism into users’ feeds. And it does not fix the fact that social media companies are not accountable to New Zealand law or to the communities they serve.

In contrast, the UK’s Online Safety Act 2023 holds platforms legally responsible for systemic harm. It shifts the burden of online safety away from individual users and onto the tech companies who design and profit from these systems.

New Zealand once had the opportunity to move in that direction. Under the previous government, the Department of Internal Affairs proposed an independent regulator and a new code-based system to oversee digital platforms. That work was shelved by the coalition government. Now, we’re offered a ban instead.

Some may argue that regulating big tech companies is too complex and difficult — that it is easier to restrict access. But that narrative lets platforms off the hook. Countries like the UK and those in the European Union have already taken meaningful steps to regulate social media, requiring companies to assess and reduce risks, improve transparency, and prioritise user safety. While these laws are imperfect, they prove regulation is possible when there is political will. Pretending otherwise leaves the burden on parents and young people, while the systems that foster harm continue unchecked.

What real online safety could look like

If the National Party, or the government, truly wants to protect young people online, it should start with the platforms, not the users.

That means requiring social media companies to ensure user safety, from design to implementation and use. It may also require ensuring digital literacy is a core part of our education system, equipping rangatahi with the tools to critically navigate online spaces.

We also need to address the systemic nature of online harm, including the rising tide of online misogyny, racism and extremism. Abuse does not just happen, it is intensified by platforms designed to maximise engagement, often at the expense of safety.

Any serious policy must regulate these systems and not just user behaviour. That means independent audits, transparency about how content is promoted, and real consequences for platforms that fail to act.

Harms are also unevenly distributed. Māori, Pasifika, disabled and gender-diverse young people are disproportionately targeted. A meaningful response must be grounded in te Tiriti and human rights and not just age limits.

There’s a certain political appeal to a policy that promises to “protect kids”, especially one that appears to follow global trends. But that does not mean it is the right approach. Young people deserve better. They deserve a digital environment that is safe, inclusive, and empowering.