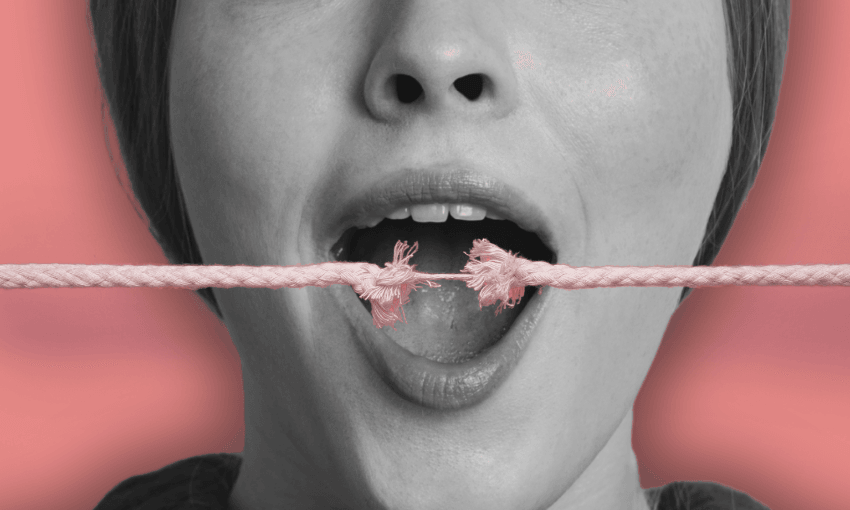

It’s a whole-of-politics problem – but is more vexing for the left, because it is progressives who seek change most profoundly. Duncan Greive attempts to persuade you all.

There’s a clear and present danger in contemporary politics – which is conducted on global platforms and accessible from anywhere – to find yourself drawn to and deeply invested in races which occur thousands of miles away and can only obliquely impact your life. For many of us it’s US politics, a subject so transfixing that a former National leader has a podcast devoted to it, and one in which the recent result of a single city’s Democratic primary – not even the actual mayoral race – felt more gripping than our own political drama.

Zohran Mamdani’s victory in the New York Democratic primary felt important, a shifting of the bounds of acceptable policy. It has transfixed people all over the world, with its promise of a new style of leftist populism that is manifestly very popular, particularly when set against the tainted establishment approach of Andrew Cuomo. Simon Wilson at the NZ Herald wrote observantly about the lessons Mamdani’s victory might contain for Labour here.

But in the context of the US, New York is Wellington Central – the most liberal 3% of a much more ideologically diverse country. I found another US politician more persuasive, one with a powerful theory about change and how to achieve it. Sarah McBride is a first-term congressional representative from Delaware, and notable as the first openly trans person to serve in that institution.

On a recent podcast appearance she tabled an argument she summarised as “we’ve lost the art of persuasion” – we meaning the Democrats. It presents an explanation for why the progressive left has had trouble convincing people of its positions in recent years. Essentially, McBride’s theory is that the left has stopped trying – whether they’re aware of that or not.

How to change a mind

It boils down to the way complex issues are increasingly framed in absolutist versus nuanced terms, and the way that seems to be having the opposite effect of what you presume is intended. Instead of bringing moderates over to a side, the absolutist style chases them away; effectively saying that unless you buy the whole of an argument, you’re unwelcome. I’m talking less about our political leaders than their partisans – who might target a slower-moving or more uncertain middle, versus the near-hopeless task of persuading the persuaded.

This can be framed in terms of compulsion (“you must believe this”) versus persuasion (“let me make my case”). As with so much of our current culture, it was trending a particular way, then supercharged during Covid. It exists in many issues which have high salience to a group along with relevance to wider society – climate change, education reform, crime and policing, trans rights.

It often starts with an entrenched and emotive position – say, that trans women should be allowed to compete in elite sports – which polling suggests (we have too little done here, but can extrapolate from international results) gets less popular the more it is discussed. McBride spoke directly to this, noting that in the last few years, during which trans issues have been more present in the public conversation than ever before, “by every objective metric, support for trans rights is worse now than it was six or seven years ago.”

She took care to make clear that is partly the result of a deliberate campaign from opponents. But she also believes that the style of argument – passionate but frequently dismissive of even good faith questions – has not helped achieve its stated aims. That the making of the case (from trans people, but more often their allies) has often hurt more than helped.

“I think some of the cultural mores and norms that started to develop around inclusion of trans people were probably premature for a lot of people,” she said. “We became absolutist – not just on trans rights but across the progressive movement – and we forgot that in a democracy we have to grapple with where the public authentically is and actually engage with it.

“We decided that we now have to say and fight for and push for every single perfect policy and cultural norm right now, regardless of whether the public is ready. And I think it misunderstands the role that politicians and, frankly, social movements have in maintaining proximity to public opinion, of walking people to a place,” she said. Compromising, in other words. She was talking about trans issues in America, but you could substitute the fight and the location for dozens of others the world over.

The rights and wrongs of a particular issue have become less material than the crucial question: is the approach, that style of argument, working? That seems to be the most important element, but one which is not considered nearly so crucial as the moral integrity of the position. It’s often about where you spend your energy; in progressive circles it can appear to be scrutinising your supposed allies for ideological purity, then issuing infractions or ostracising those found wanting.

It leads to a more ideologically aligned tent, sure, but one smaller than it was before. And because these arguments play out in public, mostly on social platforms, they have the effect of making any quiet observer with private questions or doubts feel like they too are unwelcome.

This is an all-of-politics problem, but it is strikingly more prevalent on the left. For example, the level of disagreement between Act and NZ First, our two minor parties of the right, is vast, whereas Te Pāti Māori and The Greens can feel like one movement, such is the level of agreement. NZ First and Act seem to almost enjoy disagreeing disagreeably, whereas even relatively minor differences between leftist parties and supporters can feel anguished to the point of being unresolvable.

What might a different technique look like?

Instead of policing your own side, the alternative is trying to persuade an open but cautious middle. To do the latter requires a very different approach and perhaps a more strategic theory of change. One which necessarily involves taking a position some distance from where you might seek to ultimately end up.

We live in a democracy, and even if you, like Te Pāti Māori’s Rawiri Waititi, believe it represents the “tyranny of the majority”, that is unlikely to change. As McBride says, movements which progress incrementally and in lockstep with public opinion – ahead of but not out of reach – are more likely to be durable, and far less likely to see a harsh over-correction in response. Civil rights in the 60s and gay rights more recently were games of inches, she says, with legislation and public support walked forward, with an eye on perfection but not a demand that we achieve it immediately.

What’s hard is that so many of these issues are highly charged, feel urgent, and really do impact people unequally. The planet is heating now. If you consider the police a racist institution, why would you reform it piecemeal and not wholesale? How many generations must wait for a true honouring of Te Tiriti? Trans rights really are backsliding in many places.

To give up on that perfect solution can feel like a form of betrayal. But only if understood in those terms. If it’s instead framed as a negotiation with a longer time horizon, one which might take years but will more likely endure, then it might be more palatable. To many passionate activists, such compromise might be unacceptable. Also, sometimes fury seems the only appropriate response to reality, and you’re less concerned with the outcome than a gut howl. But the question needs to be asked: have the 10 years or so in which this has been the dominant style of argument felt like progress to you?

The dangers of the coalition

Adjacent to the style of argument is the notion of a coalition. As well as the coalition governments of MMP, all parties are coalitions to some extent – National is famously a mix of farmers and businesspeople. But on the progressive left there is also a kind of moral coalition. How that manifests is a sense that to be a true ally you must believe in a very specific view on a broad basket of issues.

That can feel like it goes for everything from charter schools to climate change obligations to LGBTQ rights to tax reform. Each is of consuming interest to various people; yet if you hold a contrary (or even unsure) view on any topic – especially if you’re crazy enough to air it – you’re at risk of being tossed from the group.

To be clear, there is a proportion of the online right which is gleefully encouraging this dynamic, beckoning with open arms to anyone who might feel unwelcome on the left despite agreeing with the majority of its stances. They’re beyond activists’ control, however – unlike the current progressive approach to persuasion.

In his conversation with McBride, podcast host Ezra Klein argued that the absolutist approach to argument has come from “the movement of politics to these very unusually designed platforms of speech, where what you do really is not talk to people you disagree with but talk about people you disagree with to people you do agree with.” Platforms like Facebook, X and Instagram incentivise the production of content which stakes out increasingly extreme positions, because a more moderate (and often popular to general audiences, according to polling) stance is unlikely to provoke the engagement that expands the reach of any given post.

It leads to a paradox, whereby extremely online coalitional activists of both sides draw their parties to ever more fringe positions. The reason it seems to be more damaging to the left’s intentions is that even quiet observers of these hard lines can be made to feel rejected. Those on the right are harangued and insulted, but there is less intimation from their peers that they are no longer welcome – just that they’re an idiot.

There might be good reasons for a high threshold to acceptance: solidarity among different causes is a fundamental tenet of many reforming organisations, from unions to NGOs. But it does have a troublesome interaction with democracy, in that demanding agreement with every joined up position inevitably means losing some small but meaningful support. It’s hard to win an election that way, particularly on a national rather than citywide scale.

It’s a more vexing problem for the left, because it is progressives who seek change most profoundly. The conservative part of the right is about the status quo, seeking to defend an existing position, or return to an imagined vision of the past. The left seeks progress – to change the future. In this way, persuasion matters more, which is why it’s strange that it is often practised less, and exists within a framework which allows for little dissent.

Is there a better way?

There is a deep disdain for moderates or incrementalism today across all sides – big centrist parties have either been hauled to the fringes or seen more radical parties make big gains, if not usurp them entirely. It’s easier to describe another approach than perform it, and would require a major change in the philosophy and style of our current politics, and it’s made far harder by social platforms which are so resistant to that approach.

Yet it’s worth at least considering. Activists of many stripes might believe that their goals are sufficiently important as to justify staking out positions well away from public opinion, and sometimes seem indifferent to the fact their actions seem to make their causes less popular. Think of Extinction Rebellion protestors gluing themselves to motorways or splashing paint on artworks, even as the politics of climate change regress, in near lockstep with the more disruptive demonstrations.

It’s deeply unfashionable (I look forward to the comments lol), but maybe the best way to achieve small yet lasting gains is step back from expectation of perfect policy – at least for now. Holding out for them feels crucial, but if the way you’re going about it makes the position less popular, maybe it’s worth arguing for something more achievable, to take that first step. In the hope it might actually change a mind, and get you incrementally closer to what you really want, rather than ever further away.