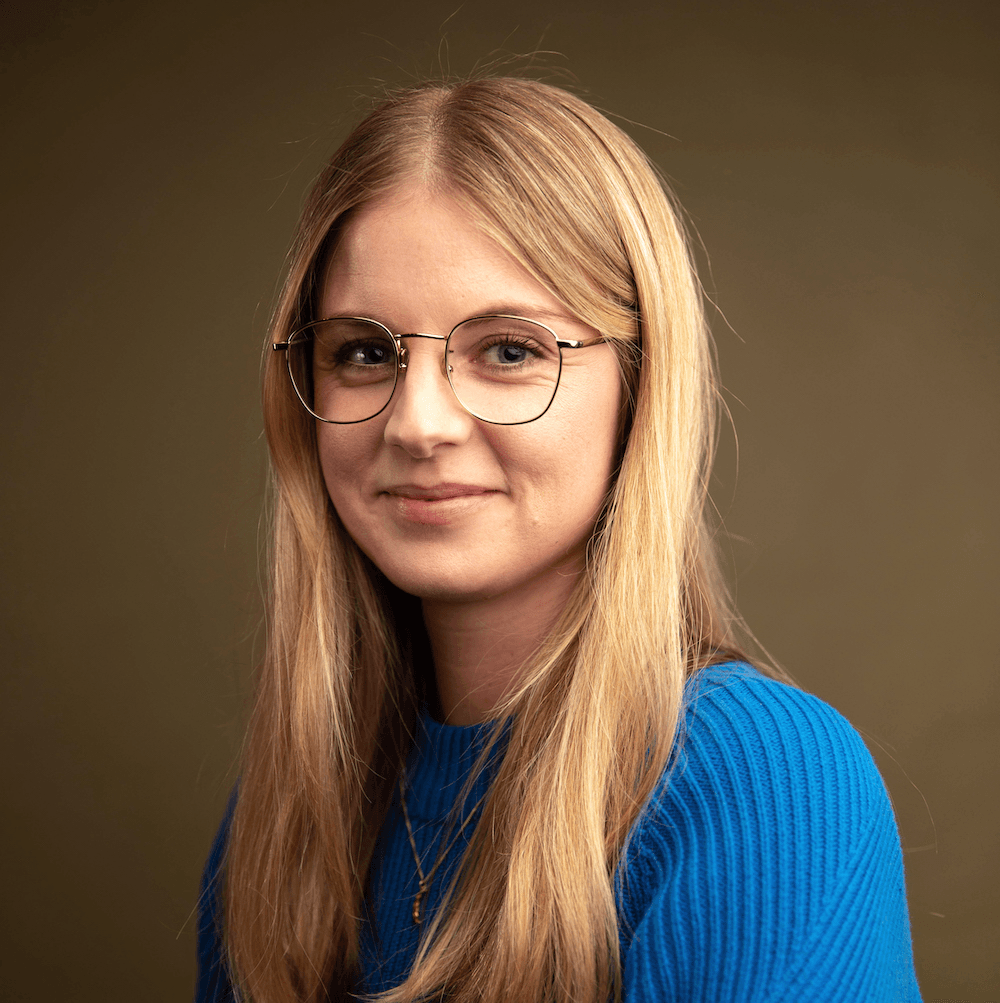

Alex Casey talks to Ōtautahi musician Lukas Mayo, aka Pickle Darling, about channelling their album anxieties into a video game.

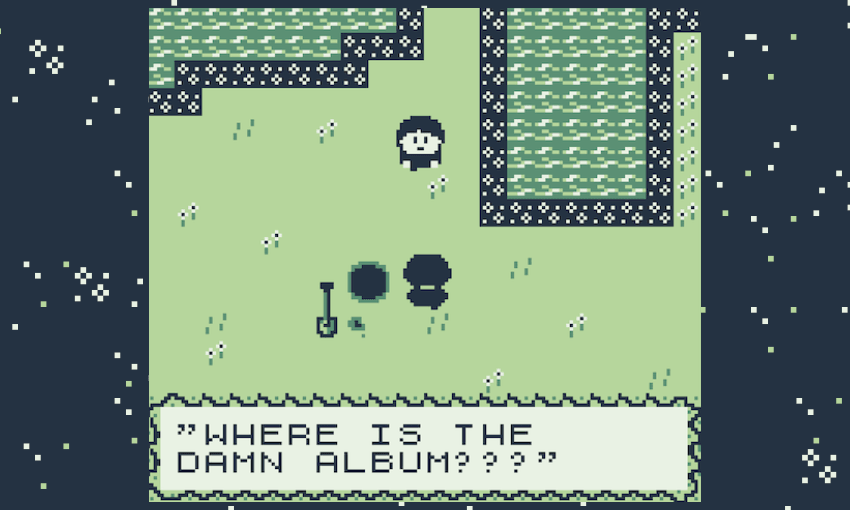

It’s not long into Pickle Darling: The Game that you are confronted by a curious shapeshifting figure, one cycling through various faces at warp speed and flanked by two ominous burning torches. “I am the New Zealand music industry,” the pixelated spectre announces. “Do you have any burning questions?” Pickle Darling, aka you, has prepared one earlier. “Why do you hate me?” The music industry, still flickering between sunglasses, a frown and a smile, responds.

“We don’t hate you. Why does every Christchurch band ask the same thing?”

This is but one of the many tongue-in-cheek obstacles encountered while playing the new video game created by the Ōtautahi bedroom pop artist also known as Lukas Mayo. “For me, I’ve always used Pickle Darling as an excuse to make things I want to make and just do what I think is fun,” said Mayo. “I’m a big fan of doing something in an accessible, achievable way and not necessarily worrying about if it’s good or not. I’m not a very good game maker, but I think it’s fun starting again at something as an amateur.”

Mayo first became interested in making a game after working with Fnife Games, the Ōtautahi indie studio behind Small Town Emo and Shelflife: Art School Detective, on the soundtrack for an upcoming demo. Created entirely on GB Studio, which allows people to make Gameboy games without any coding experience, Mayo saw a lot of parallels with the lo-fi bedroom pop community in which Pickle Darling was born. “It’s mostly online and embracing amateurish-ness,” they explained. “The GB Studio Community felt like that and very accessible to me.”

While trying to get started on their next project off the back of their critically acclaimed 2023 album Laundromat, Mayo started to feel a familiar creeping sense of drudgery when it came to making music. “As soon as something starts to do well and you have momentum, it no longer feels like a hobby, it feels like work” they said. “There’s pressures that come with other people’s money being in it, and it becomes less low stakes. As it gets harder to make music, you’ve got to think of ways to make it fun for yourself.”

So arrived the idea to make a video game about the “mission” of making an album. “I started it without a plan, which is the way I do music – writing without an end goal in mind,” said Mayo. “I wanted it to be quite meta and self-referential, quite silly, but also quite honest.” That meant addressing some of the perceived “obstacles” that get in the way of the process. “But what are those obstacles? Who are these gatekeepers? Or who do you think are the gatekeepers? And are they actually the gatekeepers at all?”

As described earlier, the first of these imagined roadblocks is encountering a character representing the New Zealand music industry, who sparks some deep philosophical questions about the north/south divide. “I think a lot of Christchurch musicians feel like they have to scream three times louder for anyone in the New Zealand music industry to notice you or get any sort of recognition,” said Mayo. “I don’t know how actually true that is, but it is a real feeling.”

The game also visits an imagined New Zealand music hall of fame, lined with pixelated album covers charmingly rendered by artist Christiane Shortal that create a thrilling guessing game within the game. More distinct album art like Marlon Williams’ ‘Make Way For Love’ and Lorde’s ‘Solar Power’ will be immediately recognisable, but the eyes might need time to decipher Aldous Harding’s ‘Party’ or Vera Ellen’s ‘Ideal Home Noise’ among more abstract offerings. “The Hans Pucket cover was the hardest one.”

In another instance, you meet a forlorn music writer lamenting the death of print journalism. “I grew up reading music magazines like Q and NME, and remember watching them slowly disappear,” said Mayo. “So many musicians talk about critics as if we’re pitted against each other, but that’s not the case at all. No music journalist is making big dollars or gatekeeping anything. The Spotify algorithm is the real gatekeeper. Anyone that is actually a human being is on the same side as us.”

In externalising some of their reflections and anxieties around making music in Aotearoa, Mayo found making the game to be quite therapeutic. “Part of the story of the game is getting to your real motivation, or the real thing that’s holding you back,” they said. “I have a natural tendency to be quite cautious and I could easily move through my life in quite a fearful way and blame everything else apart from myself for why I don’t do something. This was a bit about trying to recognise that in myself.”

Where characters like the music industry, critics and label executives could have easily been rendered as evil boss figures, Mayo found it was much more interesting to make them more nuanced, understanding types. “Then they are not actually your enemies any more, and I’m more ripping into myself for the frustrations I feel for being an idiot.” It’s a level of vulnerability that will likely resonate with others in the industry. “I hope other musicians play it and feel like I’ve tapped into something that no one talks about.”

And for all these imagined hurdles and gatekeepers, frustrations and procrastinations, is there actually a new Pickle Darling album coming at the end of the tunnel? Mayo paused for a moment, searching for the right words.

“All the answers are in the game.”