When you’re a young person in the care system, your few possessions become treasures. That’s part of the reasoning behind a programme distributing pounamu to tamariki and rangatahi in state care – all 6,000 of them.

There are more than 6,000 children in state care in Aotearoa, and a new initiative led in part by care-experienced tamariki aims to give them all a taonga of their own.

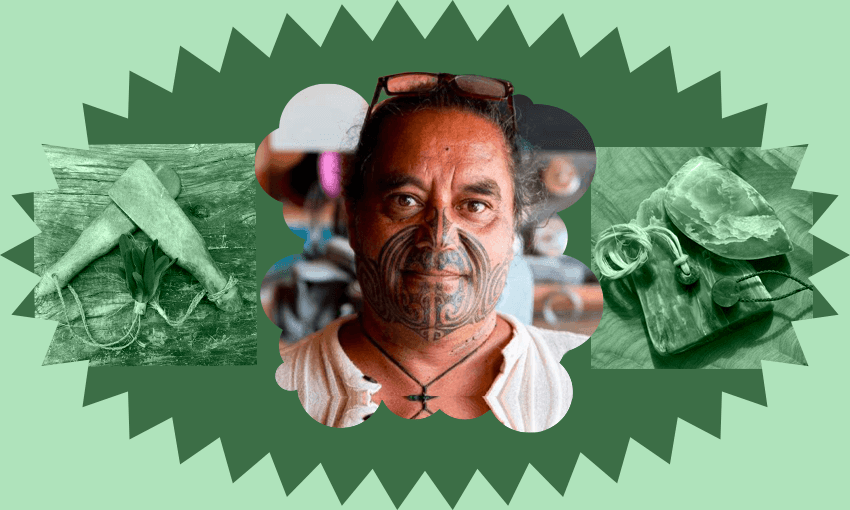

Tū Māia is a partnership between the whānau of Nelson-based carver Timoti Moran (Tainui/Ngāti Porou/Ngāpuhi/Ngāi Tūhoe) and independent NGO Voices of the Young and Care Experienced (VOYCE) Whakarongo Mai. After an initial gifting of almost 60 pounamu pendants, they have set their sights on an ambitious 6000 more, at a rate of 100 a month, uplifting the mauri of some of Aotearoa’s most vulnerable tamariki and rangatahi through a reconnection with Māoritanga.

The seed of the idea was planted when Moran attended a keynote address given by VOYCE’s national care-experienced lead Tupua Urlich (Ngāti Kahungunu), who was a witness in the Māori hearings for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care.

“He had just come out of state care and when he told his kōrero, nobody out of the 450 or so people in the audience had dry eyes,” says Moran. “His honesty, and the way that he spoke – when he finished his kōrero I went up to him and I took my pendant off and put it around his neck.”

Moran saw echoes of his own past in Urlich’s experiences. When Moran was young his own father went away to prison, leaving behind 14 dependents. The welfare system moved in to uplift the kids, taking one sister, with the remainder spending time with whānau across the motu.

“During that time, my mum had a pounamu hei tiki, and we all just revered it. I don’t think I ever even picked it up. So between that and Tupua’s reaction when I gave him a taonga, which was the same reaction I felt towards my first piece, that made me think that if we could give every child in care a pendant, this is how they will feel.”

Urlich, who was uplifted at six years old, left care at 16 and initially struggled to process his experiences, which included violent abuse by a state-appointed caregiver.

After running into trouble with the law for “drunken disorderlies on the daily – that sort of thing”, Urlich found himself in a youth offending programme which provided opportunities for wraparound support during his transition out of the system.

“I got linked in with this organisation and the director was talking a lot about the importance of advocacy. I had many opportunities to advocate on behalf of my own experience and one of those opportunities was a position working alongside an expert advisory panel chaired by Dame Paula Rebstock looking at the review and overhaul of CYF to Oranga Tamariki. In that process they saw the need to actually understand what is going on from a young person’s perspective in the system.”

But while the eventual rebrand was intended to demonstrate the state’s increasing focus on rangatahi, Urlich says the system remains overwhelmingly Pākehā and misaligned with the needs of Māori.

“My honest opinion is that they don’t deserve the name Oranga Tamariki, I think it’s an abuse of our reo. Maybe they thought it was a way of showing the direction they’re heading but, you know, get your waka right before you rebrand it. As Māori we are removed from our culture and forced into a system that does not value that. They might say they’re tika and pono but that is just words on their wall, it’s not reflected in their day to day practice.”

Urlich’s rediscovery and reclamation of Māoritanga outside of the system was a critical tool in overcoming the trauma he experienced within it, he says.

“For me, culture really pulled me through the trauma and the negative experiences of care. When you’re in care you’re constantly moving towns and moving schools so what’s the point of trying to fit in? The moment I was introduced to tikanga Māori I realised I belonged to something bigger and better than the care system.”

Moran, who recently received his mataora, says the process has created an increased sense of responsibility in his own life. Wearing his whakapapa, which Moran traces back to the Kingitanga movement, has meant inheriting the role of a matua.

“It made me grow up. Gone are the days of being an idiot. I really had to watch my words because, being the youngest in my whānau, I was always pretty cheeky. I had to really curb how I speak and get used to the role of being an older man. I was always the baby and so I always had that mentality of being the youngest.”

“Having my mataora in a public space means that everything we do has to be tika. When we say something, we mean it. With Tū Māia, if I can’t stand straight, then I felt I couldn’t do the programme. It’s been a great thing for Tū Māia, to be pono, which it really has pushed me to. The mataora itself links me to pounamu.”

The whakapapa of pounamu itself connects rangatahi to a lineage, says Urlich. A lack of possessions can be psychologically damaging to children in care, Urlich says, particularly things that come from outside of the system. It contributes to a lack of grounding, stability and self-worth, leaving the care-experienced in the role of the outsider.

“The gifting of pounamu is an opportunity to connect to our culture and even for non-Māori, a lot of tamariki and rangatahi in care don’t have many things that belong to them,” says Urlich. “Having possessions is really important and especially pounamu, which is incredibly healing. I just love the whakaaro around pounamu – we’re not owners, we’re guardians, and we’re just guiding it along on its journey. It’s that connection that you can make with something in your own life that is yours and it doesn’t include the system or any of that stuff. It’s pride. And it comes with a sense of responsibility, too.

“When I received that pounamu and even years later, when I put it on I have a sense of pride in the knowledge that I come from greatness and that I’m not just a product of the system. I’m far more than that. And often that’s all you need, is pounamu to remind you of that.”

The programme aims to change the narrative of state-experienced children, says Urlich. Those who go through the system are pigeonholed as either survivors or victims, a paradigm emblematic of the state’s assumptions of the futures open to rangatahi.

“After care, you’re a victim if you don’t manage to turn your life around and a survivor if you do. Pounamu reminded me I was a survivor but I was also more than that. Yes I made it out the other side of traumatic experiences, but I have proven people wrong and I’ve done my people proud by not falling into the future that the state had determined I would have.

“The state failed as a modern-day coloniser because it didn’t detach me from my culture forever and in fact it made me more hungry to embed my whānau and those of our care-experienced tamariki in those values and this way of life.”

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.

Follow our te ao Māori podcast Nē? on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.