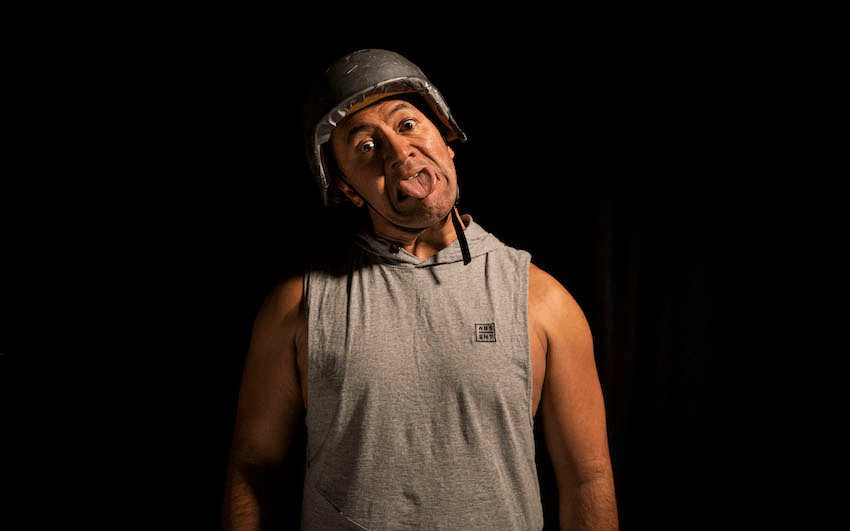

With his play Shot Bro: Confessions of a Depressed Bullet, actor Rob Mokaraka has been helping people from all over New Zealand to open up about mental health struggles. A new documentary explores his journey.

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of suicide, violence and abuse, which may be triggering to survivors.

In late July, 2009, actor Rob Mokaraka, dealing with years of depression and on a suicidal mission, called the police on himself. He told them someone had broken into his house, described his own build, and when the police showed up, ran onto the street armed with a meat cleaver and a ladle wrapped in a teatowel, and stepped towards them.

He was shot in his chest. The bullet just missed crucial organs, leaving him alive and gasping for breath and forgiveness in the middle of his quiet, residential street. Eleven years later, the scars from surgery to remove the bullet are still clear but Mokaraka’s journey of healing has been just as long, as explored in his one-man play, Shot Bro: Confessions of a Depressed Bullet.

Now a new documentary Shot Bro, based on his life and the play, gives a glimpse into the world of someone still recovering from the physical and mental scars of his attempt at death.

In the ten years from 2009 until 2019, two thirds of people shot by police in New Zealand were Māori or Pacific. Mokaraka is one of them. He says no planning went into the decision of how he chose to die that day, but after years of watching Māori men being shot by police, it seemed like an easy way to go.

“I saw young Māori people, men, being shot by police when I was growing up so I just thought ‘I’m the prime candidate’,” he says.

Now, after years of healing himself, he is trying to heal the system that puts Māori lives so disproportionately in danger from police. The Armed Response Teams that were trialed in New Zealand at the start of this year are a prime example of how the system continues to put disproportionate pressure on Māori and Pacific communities. Mokaraka says the trial showed that the systemic biases in the police are still very much in play.

“Those laws about arming police were done after the Christchurch shooting, which was done by white people, but they arm the police to go into brown neighbourhoods, so what’s going on there? There’s just inequity and inequality and bias.”

Over the six-month trial period, nearly half of all those apprehended by the Armed Response Teams were Māori. Mokaraka says the racial problem lies with the lack of training and a system stemming from colonial laws.

“I have friends who used to be in the police and I have friends who are still in it and they’re good people but you have a whole system that is archaic. It’s archaic and it needs to be revised, especially because racial profiling and armed police officers are ill-equipped, ill-trained and it’s just a cocktail for volatility.”

He doesn’t think efforts to “diversify” the force will somehow reduce the bias within it.

“It’s the system. You can put heaps of new great costumes on everybody but it’s still the same system, and that’s across the board with mental health and across the board with the Department of Corrections, because they’re from the same archaic laws that we adopted from the British.”

Having performed his play up and down the country, Mokaraka has become much more aware of the forces that led to his poor mental health in the late 2000s, but he’s not claiming to be an expert in anything other than his own experiences. Still, he says he learns something new through the responses he receives after each performance of his play.

“By sharing I’m learning from other communities and also professionals in the mental health sector so it’s very validating that you’re not alone, because all these people I talk to are also hurting.”

After every performance, Mokaraka leads a panel discussion about mental health and depression. It’s a raw conversation, and people are encouraged to open up as they feel comfortable. The reactions are different with every group he visits, but he says he continues to be moved by those who use their strength to stand up in front of the crowd and speak their pain.

“When someone has held onto something for 30 years, it’s like they’ve been trapped in a dark room and they step into the light for the first time… To see that and feel that in a room is incredibly humbling because that means there’s a lot of trust that they have put into me to provide the space of safety, and they don’t have to.”

One of Shot Bro’s most poignant moments comes when Mokaraka speaks to his sister for the first time about that night in 2009. Talking through your pain is a vital step in recovery, he says now, and he’s committed to creating a space at home where his two daughters feel comfortable sharing their problems with him. He encourages other parents to not shy away from conversations about emotions with their kids.

“Kids only think from the heart, adults, overly complicate things, over analyse and over think things… My daughters know dad was shot, and I say ‘I’m going around and helping people so that they don’t get hurt’. They understand that. My little one checks up and says ‘that’s not going to happen again is it Dad?’ I say ‘no my darling, Dad knows now.’

“When you’re talking about parental figures, it’s the parent who has to be brave. The child is already the bravest.”

In Mokaraka’s experience, Māori men in particular often hide from their feelings of depression and anxiety, and that’s behaviour that’s been passed down for generations. He says there’s a common misconception that men need to be staunch, unforgiving and brave, and this often overtakes the human need for connection that’s beyond physical.

“‘Be soft, not weak, be strong, not violent’. I think people have it confused when they’re looking at those things. If I’m not strong then what am I? You’re in control. It’s about learning how to become the warrior and the poet and the healer and the gentle father and the husband.”

After changing his own future through writing, performing and learning to speak out about mental illness, Mokaraka has just one goal for his work: to encourage others on the same path.

“I want the documentary to hopefully save a life.”

Shot Bro is presented by The Spinoff and Māori Television. Made with the support of NZ On Air. Watch it here.

Content warning: This documentary contains themes of suicide, violence and abuse, which may be distressing to viewers.

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor.

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP).

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat.

Samaritans – 0800 726 666.