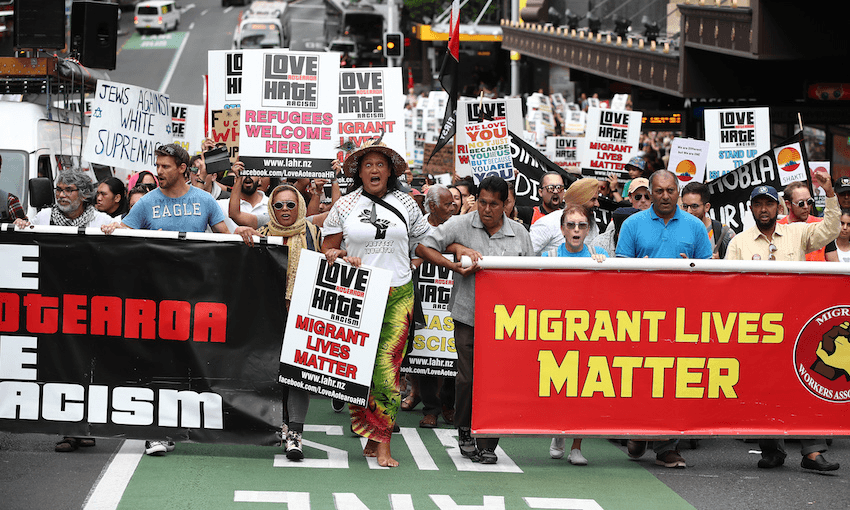

Samuel Te Kani attended Sunday’s Love Aotearoa Hate Racism march in central Auckland, and found a confusing mix of love, solidarity, conspiracy theory and violent rhetoric.

I’ve never been especially drawn to activism, not in any conventional sense. In an era when criticality recognises the innate politics of everything, what is the function of ‘classical’ activism anyway? This is probably a wrong opinion in the minds of my fellow self-identified liberals, the ones who participate in sit-ins, rallies, marches, the whole 1968-esque shebang. They might say that mine is the opinion of a self-satisfied capitalist who has little interest in helping others because their lot in life is relatively good compared to the reality for the actually marginalised and oppressed. Maybe there’s some truth in this. But we all know how difficult it is to be truly objective about ourselves.

With that as a personal disclaimer, I want to talk about the anti-racist rally on Sunday in Aotea Square. I attended at the behest of my partner and best friend even though, for whatever reason, my energy levels have been harrowingly low of late, and I knew I wouldn’t ‘enjoy’ myself.

And I did find the rally hard yakka, but it wasn’t because I was tired. It was the tone of the rally itself. This was the second Auckland event of the weekend commemorating the Christchurch attacks. I couldn’t attend the vigil at the Domain on Friday so don’t know exactly how that played out, but I’ve read some comments that the tone there was overly political. This is both a valid and problematic complaint. It’s valid in that a vigil is traditionally affective, a site of semi-sacred commemorative hush. But what good is this imposed silence if it replaces what could otherwise be a platform for critical discussion of a period that, for most of us, has been marked by confusion and terror?

Back to Sunday. Of all the things I expected to find grating that day – moving at a glacial pace alongside white girls with dreads and hipster families, the awkward lulls in group chanting, being told not to smoke for the sake of the children – the critical aptitude of guest speakers (or lack thereof) was not one of them.

It’s probably a distasteful call to vigilantism to proclaim, as one speaker did, to a crowd still recovering from the trauma of one of this country’s most vicious instances of gun violence, that a certain notion within tikanga Māori suggests sending those who hurt you to the cemetery. It’s also a horrendously reductive framing of Māori as warrior-people, which I rub up against in my daily life with more frustration than anger. We are not warriors, cannibals, mystics, and we are not here to salve your urban malaise and existential angst with ancient remedies. Save that for your yoga teacher. We are people and that is that – though if someone Māori wants to play with this Pākehā idea that we are animist-aboriginals with flesh-memories of using spear and arrow, then here’s hoping their performance is used to grab some resources to help empower Māori communities.

That said, I appreciated the solidarity hidden in the violent sentiment, and was warmed by the Muslim speakers who seemed genuinely humbled and moved by their reception from the crowd. What a shame it required the path it did.

The Muslim speakers themselves were as astonished as you’d imagine, overwhelmed still with both the horror of the event itself (as we all are) and the outpourings thereafter from a New Zealand which, up to that point, can’t be said to have embraced multiculturalism much beyond the necessities of trade. But even before we all set off on the march I had a sour taste in my mouth, induced by the dangerous suggestion by one of the speakers that Mossad was a silent backer of the Christchurch mosque attacks. After that, I saw one attendee remove his yarmulke, and I don’t blame him.

Whatever the suspicions currently circulating regarding the convoluted thread of culpability for Christchurch, these speculations are best left to either to authorities or internet forums, and were definitely out of place at a march whose objective was to stand against fascism and white supremacy. That said, the anxieties of the Muslim community are of course unfathomable to anyone else right now – even more reason for such allegations to be made through proper channels where they can be evaluated and investigated, if necessary.

Another thing I found hard to stomach: a crowd that was still emotionally raw being egged on during a pro-union speech to jump and shout at the prospect of a ‘war’ on racism. Again, poor tone and lazy rhetoric. Dangerous even. Reactionary, to say the least. And also entirely understandable, up to a point.

Of course everyone’s initial reaction is to want swift retribution on responsible parties. But such a discourse of Us and Them (We will root out all racists in the workplace! Cue righteous cheering) neglects the culpability of systemic racism, something which this country has allowed to flourish in silence. Clearly, racism in the workplace is a particular issue, but a call to fight racism is not the same as challenging systemic racism, for starters because it fixates on generic examples and in doing so fosters blindness to more insidious instances (like thinking that all Māori are warrior-people is a compliment and not systemic othering) – and also because it leaves ‘racists’ as a remainder, somehow outside the scope of society.

I don’t have a plan for re-education of racists in the workplace, but I do know that deploying a rhetoric against them already loaded with clear winners and losers will only create an underclass of the disenfranchised with an even bigger chip on its shoulder. And surely the Christchurch attack should warn us that those can be key ingredients in the radicalisation of bigots (just add firearms). Absolutely, purge the workplace of racism, but perhaps also structure contingencies to offer reparations? Maybe these things already exist (compulsory sensitivity training et cetera), and if they do then that’s marvelous. But maybe we should be more aware of ourselves, seeing ourselves not just in the victims but also in the perpetrators. Let’s replace the route of indignation with one of mourning for the loss, and then motivation for the remaining work to be done, the gaps to be bridged, the cultural blind spots to be filled, lest we continue deriving our self-image from wounds and not from ideals. Yes, I feel anger and resentment towards those responsible, but I also don’t want to let this feeling blot out the painful fact that this is not an anomaly. The was allowed to happen through a logical sequence of events, insidiously quiet allowances coded into a system we all share and contribute to. This is not mystical holism. This is fact.

Aside from all this, the rally’s turnout was heartening. But motivations have to be questioned, personal premises adjusted and readjusted so that they triangulate with more openness, more agility round the shifting configurations of our society and the many disparate threads running through it. I got the clear impression around me of a desire to be seen at this event – that might be cynical of me, but I couldn’t shake it. What use is solidarity if its motivations are that hollow?

I don’t know where we go to from here, but if we’re going together then that togetherness has to be more than a posture. Agreed?