Nadine Millar writes a love letter to her beloved Porirua, and asks ‘What’s in a name?’

A few years ago, in 1994, a local businessman started an unsuccessful campaign to change the name of Porirua. Chris Gollins, a real estate consultant and media personality, felt that businesses were put off coming to the city because they baulked at the name Porirua. He reckoned ‘Mana City’ had a better ring to it.

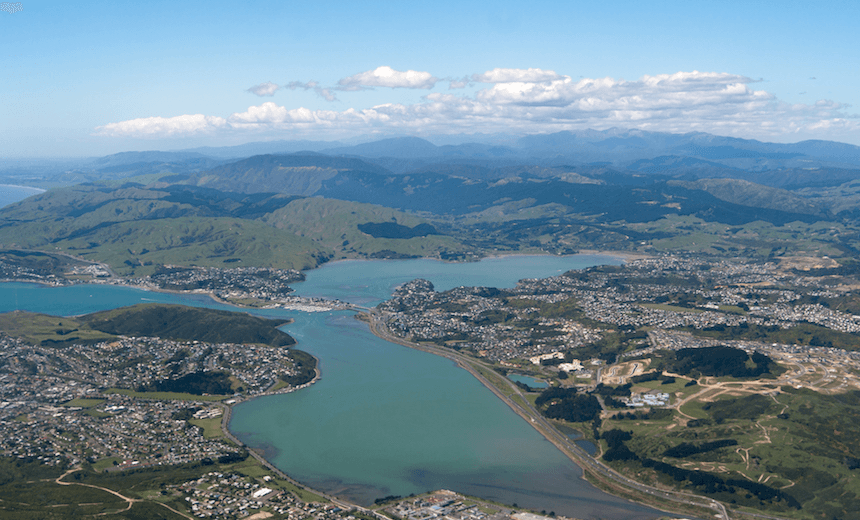

I wonder what the great explorer, Kupe, would think of that. A few hundred or so years ago, he entered the harbour we now know as Porirua, dropped anchor near Paremata, and took it all in. He must have been impressed. Here was a basin wrapped in a cloak of dense forest. Twin harbours bountiful with kaimoana.

To the east, Pauatahanui, brimming with oysters, paua, pipis, fish and eels. Stretching south, Onepoto, similarly overflowing. Surrounding both harbours, birdlife in abundance. Huia, kākā, kiwi, takahe, tuī. On a still day, the shallow waters reflect the sky.

So one kōrero goes, Kupe called this place ‘Pari e Rua’ – the meeting of two tides.

All these centuries later, I walk the steep pinch that is Whitireia at the southern end of Titahi Bay, and look out over this sprawling city. No doubt things look a little different, now. The dense native forests are gone. The tōtara, rimu, mātai and kahikatea felled, stripped for their timber and sent to the mill. Cloak removed, the knotted hills stand bare, green in winter, golden in summer.

The destruction of the forest sent silt sliding down the mountain into the inlet, filling it up and choking the sea life. Sedimentation put an end to plans to commercialise the now dwindling resources, and the birdlife disappeared. Today, houses and farmland are reflected in the shallow inlet.

Night after night, congested traffic crawls across on the bridge at Paremata, right at the place where the arms of Onepoto and Pauatahanui meet and flow out to sea. At the entrance to the harbour, hidden from view much of the time, Mana stands guard. The island’s long name, Te Mana o Kupe ki te Moana Nui a Kiwa, remembers Kupe’s great voyage across the Pacific.

These names don’t have negative connotations. They’re not a hindrance to progress. They’re part of our history. They describe the landscape and place us in it.

By comparison, the names that settlers and city councils have given our land are much more fickle. Names change with the wind. Their meanings and connotations, often, a mystery.

In Pukerua Bay, Marama Place was renamed Donlin Road after a civil engineer employed by the Hutt County Council. There’s no record of why that achievement earned him a street name, but he’s not the only council worker to have had a street named after him. Maybe chucking a street name in was part of a performance bonus.

In Papakōwhai, the street names derive almost entirely from rivers, waterways and lochs in Scotland. Why? Because one of the big bosses of the timber company in the area hailed from there. Streets in Cannons Creek remember ships, English counties and Greek gods. Ascot Park, named after one of the world’s great racecourses, celebrate the names of prize-winning horses.

Overwhelmingly, though, a street name in Porirua is most likely to commemorate an English settler, a governor general, an army captain, or a chairman. Were they worthy of the honour? It’s hard to know. The history books rarely tell us.

In a debate earlier in the year about the nearby Kapiti Expressway, some people complained that political correctness had gone mad when the council announced the road would have not one, but seven names.

The names Hurumutu, Rauoterangi, Kākākura, Unaiki, Katu, Matene Te Whiwhi and Hokowhitu were a mouthful, some said, which I thought was pretty ironic alongside other street names in the area – Ixion, Caduceus, Leicester, Azimuth, Furneaux and Molyneux hardly roll off the tongue.

As for PC gone mad, how about the time a group of council members were gifted a case of single malt after naming a bunch of Porirua streets after popular brands of whisky. Conflict of interest, anyone?

I laughed, too, when I heard one punter on the radio say that seven names was too many to remember. Back in the day, before television, the English would regularly entertain each other reciting long passages of poetry by rote. In Arabic, the word ‘Hafiz’ describes a person who has memorised the entire Koran. A similar skill set is highly valued in te ao Māori, with the handing down of mōteatea from one generation to another.

Seven names too hard to remember, really?

While Pākehā place names come and go, Māori names endure. Ours is an oral culture, so it doesn’t matter what name is recorded in a council directory because our stories will outlive all those books anyway. That’s why the survival of our classical language, or te reo o nehe, is just as important as our everyday, conversational reo and kīwaha/sayings.

That’s not to say Māori always agree about names and meanings. Kōrero will often vary depending on who you talk to. Likewise, simply breaking down a compound word does not always reveal the answers. Sometimes, you have to look deeper.

Marama Fox recently said she’d always wondered about the meaning of the South Auckland suburb of Māngere, which means ‘lazy’ in Māori. She later found out the name has been abbreviated from ‘Ngā hau māngere’ meaning the gentle winds.

This is why pronunciation matters. Place names are not just bunch a of syllables randomly slapped together, they’re pieces of a puzzle that tell stories about the past and shape our collective identity.

But frankly, just aiming for correct pronunciation is a pretty low bar. The names suggested for the Kāpiti Expressway aren’t perfunctory labels applied to inconvenience some and placate others. They’re an invitation to those of us who live here to actually engage with the history of the land we live in, the people who came before us, and the scenery we drive through every single day.

Two decades ago Chris Gollins thought he could reinvent Porirua by changing its name. He didn’t stand a chance. With only 15% of the community in support, the council shelved the idea and moved on.

It’s just as well. Every morning when I walk up Whitireia and look out across the water towards Mana, guarding the entrance to this twin-inlet harbour, I reckon Kupe got the name just right.