Nadine Anne Hura reflects on four years covering climate change from a Māori perspective, and why sometimes the best lessons emerge from the most unexpected places.

Four years ago, back in the pre-Covid era of 2019, I went to Pawarenga on the southern shores of the Whangapē harbour in Hokianga. I’d been awarded a small grant to write a feature about sea level rise based on credentials I’d mostly overstated and a grandiose pitch about presenting “a Māori perspective”.

I arrived in the dark and nearly drove straight into the sea. There was a single light on the mahau framing the marae in the distance, but it appeared to be suspended, solitary, between the sea and the sky. I opened the door of my two-wheel drive rental and leaned out. The road had vanished. All I could see was the reflection of the moon and the shape of my own, stupid face.

I shoved the car into reverse and prayed for traction. From a safe distance, I got out and squinted. Could it really be a marae floating out there in the middle of the ocean?

I looked at my phone. Google displayed a useless green dot scanning a vacant universe. I folded myself into the driver’s seat and blew on my hands. I tried not to panic. It was hard to believe I once wanted to be a war correspondent in a foreign country. I might not even survive an overnight trip to the Hokianga.

My assignment had begun several weeks earlier, at a near-impenetrable climate change conference at the Viaduct Harbour in Auckland. The language was strange, dominated by data and graphs, and frankly, boring as hell. During the breaks, I gravitated towards a man called Hank Dunn who vaguely resembled my dad. With calloused hands, thick white hair and a wry grin, Hank looked like he was about to crack up any minute. Every time he slipped out of the stale room for a puff of fresh air and a ciggy, I followed.

If I was an imposter, Hank was fully undercover. The conference agenda listed his credentials as a community researcher specialising in the field of water quality, which I soon worked out meant someone who knew their own whenua like the back of their hand. By trade, Hank was a fisherman, and he buoyed me through the yawning afternoon with stories of adventures on the high seas in which he had survived not one, but five shipwrecks.

When the conference concluded, I went home and turned my attention to the serious task of writing a climate change feature article. Alarmingly, all I had was a series of verbatim quotes from Pākehā scientists that sounded like a poor attempt at a spoken word poem:

Stranded assets, inundation, elevation

Revelation! said the scientist:

“We must review our reservations in regards to our observations.”

With the deadline looming, I accepted Hank’s last minute invitation to visit Pawarenga. I thought it might be easier to write a story about the rising sea if I was physically closer to it.

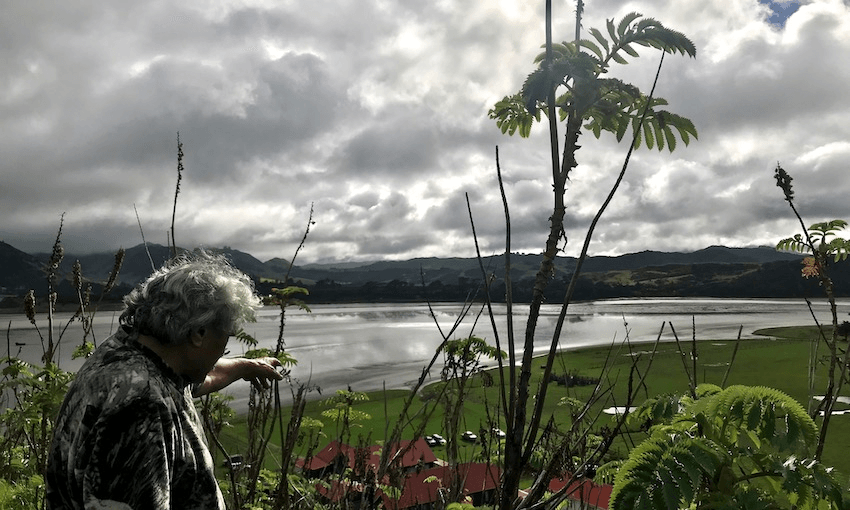

And Pawarenga is critically close. I found Hank’s place at first light, exactly where he said it would be: down the long driveway on the left, beside the creek after the second marae but before the last bridge. We spent the day walking the places of his pepeha. I learned how Te Rarawa and Te Aupōuri were named. I stood on maunga Taiao and looked down to the place where the road dissolves into the sea, giving the marae its mythical appearance by moonlight.

I took notes, just as I did at the climate change conference. But when I sat down to write, there seemed to be no clear link between Hank’s reality at ground zero, and the data and graphs presented by the Pākehā scientists at the conference in Auckland. The two worlds seemed to exist in parallel, but never intersect.

In the end, I wrote the only story I had. It read like a modern allegory: the science of climate change through the lens of five shipwrecks and five priceless Hank punchlines. Four years and several climate articles later, I realise that writing ‘How to Survive a Shipwreck’ taught me all I needed to know about the science of climate change storytelling.

Navigating doom and despondency

Over the years, I’ve come to accept that stories about climate change are a hard sell. If you’re aiming for wide readership you should probably avoid the words “climate change” at all. Unsurprisingly, none of the the most-read stories on the Spinoff last year referenced the climate crisis even in passing. I’m not salty. I get it. I’d rather be entertained than depressed too, and for most people, facing the trial of the next day is hard enough, let alone the doom of the next decade as well.

It’s disappointing, because if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the past four years, it’s that there is a direct link between the pressures and pace of our lives, and the pollution and stagnation of the rivers we live next to. Ko au te whenua, ko te whenua ko au.

Trying to pinpoint the precise links between the struggle to make ends meet and the harms to Papatūānuku driven by corporate greed is like the Rubik’s cube of climate communication. Done poorly, it’s an eye-glazing overload of information. Done well, it can scare the bejesus out of people. It can also have a counterproductive, polarising effect: some become despondent and throw up their hands and walk away. At the other end of the spectrum there are those prepping for end times.

In a podcast about climate adaptation solutions, Sasha McMeeking, a researcher with expertise in the predictors of social change, explains why fear isn’t a great motivator. “To create an autonomous sense of motivation, you can either scare people into acting or inspire them out of notions of love and aspiration and yearning. If you scare people into acting, they’ll do it for a little while but then stop. But if you inspire people through love or positivity, the motivation is more likely to endure.”

This is a critical piece of the storytelling puzzle. I remember the intimidation and overwhelm I felt at that first climate change conference. If it weren’t for Hank, I might have left. What stuck with me all this time is not the projections, but the image of Hank floating towards Aussie on an upturned fish bin. I will never forget his advice, delivered with a belly-full of raspy laughter: “The last thing you wanna do when you go overboard is panic. Panic is what kills ya!”

The point is, people might not always remember facts and details, but they will never forget critical information wrapped up inside a good yarn (see also: all the Māui creation stories).

Pre-empting distrust and denial

Taking care not to spread fear and panic is important. But it needs to be balanced with the weight of evidence that climate catastrophe is imminent and action is urgent. This presents a particular set of challenges for anyone working in the media.

The rise of mis- and disinformation in the wake of Covid-19 has contributed to scepticism and distrust of authority, especially mainstream media. This is winding us back decades in the struggle against climate denial (longer, if we start the clock from when indigenous communities first began opposing mining) and it makes the task of interrogating, condensing and translating complex information for the public, who have a right and a need to know, more difficult than ever. It carries with it a responsibility to detect corporate greenwashing and hold ministers and governments to account when they fail to uphold commitments or knowingly mislead the public.

In this light, the challenge to the legitimacy of the media is rife for manipulation, especially by those who stand to lose the most from the dismantling of hierarchies responsible for global warming. Lee Donoghue, Shorty Street actor turned NZ First candidate, exemplified this manipulation in the Young Leaders’ debate last year, describing the climate emergency as “scaremongering alarmist hysteria” in a performance that wouldn’t have won him an Oscar.

By and large, journalists are doing hard yards in incredibly challenging conditions, but the responsibility to communicate about climate is too big and too important for the media alone. We also need to advocate for better resourcing of a diversity of storytellers from across the arts – including even spoken word poetry! Look again at The Spinoff’s most popular content last year. There’s a whole raft of untapped potential in musicians, composers, comedians, podcasters, filmmakers and let’s not forget Shortland Street script writers.

Most importantly, we need to ensure that the local knowledge and expertise of the plain-speaking, straight-talking Hanks of this world is validated alongside those of Pākehā scientists. It can’t always be Māori feeling like fish out of water. And because not all trusted messengers look like journalists.

Some, like Hank, look like people we know.

A single light on the mahau

When I set out four years ago to tell stories about climate change centring Māori perspectives, I had zero climate literacy and was an ihu hupe in the world of mātauranga Māori. I’m still a snot nose, but I’ve gotten better at navigating between the parallel worlds.

One of the most interesting observations I’ve made is the contrast in mood. There is an acceptance, determination and positivity on the marae that isn’t typically found in conference rooms or government departments in major cities. The message that dominates mainstream news headlines is that people can no longer have it all. The solutions to the climate crisis read like a series of sacrifices and cost-benefit trade-offs. To read from Lee Donoghue’s script: “Going green is going to cost a lot of money.”

But under the Westminster system of rule, Māori have never had it all. Living and working and surviving in conditions of material lack and political deficit is normal. Long term, intergenerational planning for collective benefit, at deep personal sacrifice, is culturally ingrained. The rising cost of living may only now be gaining recognition as the social precipice of the impacts of climate change, but Māori have been dealing with these impacts for yonks.

In this light, the positivity and energy and laughter on display at the Hui aa Motu in Tūrangawaewae, in spite of the drastic forecast, makes sense. Change is on the horizon. It is not a political choice but an environmental inevitability. The truth of this intersects both worlds. For many Māori, it’s not all negative. The skills, way of life and collective mentality that the climate crisis is forcing upon us are those that tūpuna Māori always had, and their descendants today are fit for and ready to reclaim. In conference lingo this kind of adaptability in a crisis would be described as “climate resilience”. Hank would probably just call it having a sense of humour.

It’s easy to feel despondent when presented with data and projections that remind us of our individual insignificance. But it also misses a much more crucial point: the decisions and actions we take as individuals to positively impact the environment, also benefit us. Often, these enduring changes are fueled by simple but highly underrated things like shared belly laughs. It’s certified behavioural science.

Even writing about it is regenerative. Over the past four years I have met people everywhere, in small but growing numbers, reconnecting to a source that is brimming with potential and promise. It’s like swimming in a freezing river and suddenly coming across a ribbon of warm, life-saving, thermal water.

Or to use an analogy from the story that taught me the most: it’s like looking up to the horizon and seeing a single light on the mahau, suspended impossibly, mythical, like a beacon between sea and sky.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.