Auckland Transport wants a rail line from the CBD to the airport. Council does too. So why does a start date seem further away than ever? Simon Wilson examines what’s gone wrong and how to make it right in the dispute over rail to the airport.

Light rail is trams and heavy rail is trains

Before we go anywhere with this, let’s get one thing clear: we’re talking about trams and trains.

The politicians and planners alike bog the conversation down with their talk of light rail, also called LRT, which is light rail transit; and heavy rail, also called HRT; and also “advanced buses”, also called BRT, which is bus rapid transit, which is buses on a dedicated bus-only roadway like the Northern Busway. And all of it makes up rapid transit, or mass transit. AAARGH.

Let’s just say trams, trains and buses. Fast buses if you like, because ordinary bus services share the road with everyone else and are not rapid transit.

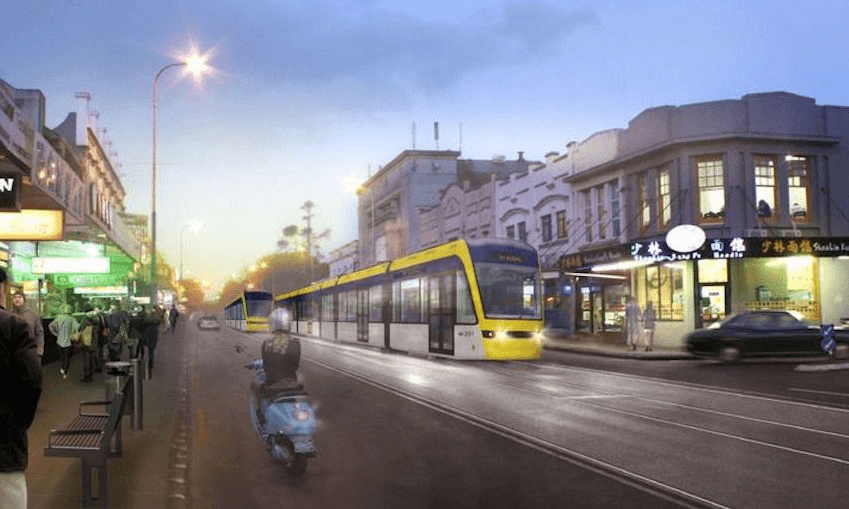

Trams: not those old tourist-attraction trams, but sleek fast modern machines. Trams are not what trams used to be, in exactly the same way that cars are no longer Model T Fords.

And trains: not the old diesel engines now used only for freight and parts of the main trunk line. The “heavy rail” trains that move people around Auckland are the smart new electric units now running on all the commuter lines.

We need to build rail to the airport now

There are now 33,000 people working in and around the airport and by 2044, say the planners, that will rise to 90,000. The number of passengers using the airport grew by 10 percent last year, to 17.3 million. It will hit 20 million by 2020 – or 55,000 a day – and 40 million by 2044 (all these figures are from a joint position paper prepared by Auckland Council, Auckland Transport and the NZ Transport Agency).

Even if we build triple-decker motorways, it will simply not be practical for most of those people to drive to and from the airport in private vehicles.

We need trams and/or trains, and the process of planning, consenting and construction for them will take a good 10 years. We need to get started now.

The economic case doesn’t exist

And yet. The shocking fact is that there is no compelling business case to build a rapid transit system of any kind to the airport.

An “interim business case” prepared in 2015 found that trains to the airport would cost about $2.3 billion and have a benefit cost ratio (BCR) of 0.49 to 0.89. That’s unacceptably low, and it’s the principal reason AT has rejected the trains option.

For trams, design and construction would cost about $1.2 billion and the BCR would be between 1.11 and 1.72. Actually, that’s unacceptably low too.

This is because while any BCR greater than 1 might seem like a worthwhile investment, in reality BCRs should be well above that. For various technical reasons the planning experts say they should be more like 3 or 4.

The economic case has changed

The costings have since been reviewed. A recent workshop involving councillors and staff from council, AT and NZTA was presented with new figures that showed the likely cost of trams had ballooned and was now the same as for trains: around $2.5 to $3 billion.

The reason? The initial BCR assumed trams would be introduced anyway and would run from the central city all the way down Dominion Rd. So the BCR considered only the extra cost of extending them to the airport. The new costs correctly include the entire project.

But despite that, the new analysis showed the BCRs had not fundamentally changed: for trains it was 0.37-0.64; for trams, something a bit over 1.0.

BCRs are not much help

What’s going on? How is it the prospect of interminable traffic snarl-ups doesn’t create more favourable BCRs? Even when that traffic is full of trucks trying to get goods to market? And air passengers trying to catch a plane? Something wrong with BCRs, you’d have to say.

The government itself believes this – it’s made several transport project decisions that are not supported by a good BCR. The Puhoi-to-Wellsford highway and the East-West Link from Penrose to Onehunga both spring to mind. Both of them have a weak financial case, according to their BCRs, but despite that are considered so important to the economy they’ve been designated Roads of National Significance.

Clearly, there’s a reality gap. On the one hand, a transportation system headed for collapse. On the other, a system of economic analysis that cannot produce a viable solution.

If anyone’s got a better way to do the economic analysis, let’s hear it. Because clearly, we need it.

Fast, frequent public transport is an essential feature of large modern cities

Let’s remember this: cities all over the world are growing, many of them very fast. That growth causes systems failures and social disarray when it is not planned for, but provides tremendous economic, social and cultural opportunities when it is. Which one do we want to be?

It’s the second, obviously. But that’s not us, not yet. Every city that has retained its capacity to function well while growing has a strong public transport network based on key rapid transit routes. Auckland’s public transport is vastly better than it was even 10 years ago, but we don’t have the network strength we need and despite the progress we’re not building it nearly fast enough.

Instead, we’re still focused on adding motorways and motorway lanes. It’s expensive, counterproductive because it encourages cars, environmentally ruinous, and neverending. But once the tracks are laid in a well-designed system, boosting the rail capacity (whether with trams or trains) is far easier: you add more trams and trains and more carriages to the trams and trains.

The need for this exists all over the city, but nowhere is it more obvious than with the problem of getting to and from the airport.

Why aren’t we building tram or train lines to the airport already?

Auckland Transport is keen. The council is keen.

But the government, while agreeing to “secure the route” (although there is more than one route: see below), has put off a decision to fund, let alone build, until someone can prove there are unicorns wandering the Bombay Hills.

It’s politics. It’s election year. The government strategy is twofold: to blame council for the problem because it is not spending enough of its $4 billion budget on transport; and to allow extra funding requests from the mayor, Phil Goff, to be characterised as Jafa greed.

Prime minister Bill English, finance minister Steven Joyce and transport minister Simon Bridges all put on their serious faces and talk about how much they are spending already to deal with Auckland traffic congestion. But English and Joyce also say the council is actually reducing the amount it spends on transport.

Their argument rests on the “interim transport levy”, which is part of the rates bill but is due to expire soon. The government essentially wants it to remain in place: why forego the revenue you’re already getting?

The council fights back

Goff and the council respond with three arguments. First, that it’s a massive breach of faith with ratepayers to make a temporary levy permanent. Second, that targeted funding is much preferred – getting road users to pay rather than all ratepayers. Yet the council doesn’t have the authority to do that: it needs the government to pass a law allowing it and that’s been ruled out.

Joyce has explicitly rejected Goff’s request for a regional fuel tax, which would add perhaps five cents to each litre of fuel. (Matt Lowrie at Greater Auckland reckons a fuel tax in Auckland would contribute $80 million a year; the Green Party and Labour both say more.)

Goff’s third argument is that if this wasn’t Auckland, the transport infrastructure we need would be 100 percent funded from government. That’s what’s usually happened in other parts of the country, he says. Which is true.

The government clearly believes there are votes to be won. Auckland votes, from those who don’t like Goff and the council, and/or still define public transport as a service for poor people rather than a core strategy for unblocking the roads. And non-Auckland votes, among all those who think we complain too much and are horrible people anyway.

Commentators everywhere are fond of saying Auckland has 35 percent of the population and therefore will be critical in the election. The government strategy suggests they think they can win by pandering to the remaining 65 percent.

Just think about that for a moment. The government is jeopardising the economic wellbeing of the city, on which the economic wellbeing of the country also rests, because it thinks there are votes in it.

Even if you think the council is also being selfish and irresponsible, who are the grownups here?

For the record, if a five cents/litre fuel tax (with a similar rise in the road user charges paid by diesel vehicles) had been in place from 2009, as Labour legislated for but National scrapped, Matt Lowrie estimates it probably would have raised $640 million by now. The Greens say it could have been over $1 billion.

Council and the government do agree on one thing: there’s a shortfall of around $4 billion in transport funding over the next 10 years, just for the plans they agree on – which do not include any kind of rail to the airport or to the Shore.

That’s an enormous gap – and it makes the government’s refusal to engage meaningfully with council seem outrageously cynical. What madness would stop anyone from introducing road-user charges, of one sort or another, as soon as possible? As Tim Murphy at Newsroom has commented, “If ever there was a tax Aucklanders should be willing to pay, it is a surcharge on petrol to help free the roads.”

Where would they go?

The route of a tramline from central city to the airport is broadly agreed on: from upper Queen St it would connect to the once-was-almost-a-motorway at the top of Dominion Rd, head south to Mt Roskill and Three Kings, then to Onehunga and across the Manukau harbour to the airport.

The route of a train line is not so clear. One option is to extend the Onehunga Line, which is a spur on the Southern Line, across the Manukau harbour to the airport. Another is to run the line from Otahuhu. A third is to extend from Puhinui, near Papatoetoe on the Southern and Eastern Lines, to the airport.

Or would it be better to run a tramline through Puhinui, all the way from Botany, down through Ormiston and the other new eastern suburbs? Or a busway (see below)?

How good are trains?

Trains should make sense. They can carry 750 passengers in a six-car set and they’re popular. We already have lines running quite close to the airport – those Onehunga and Puhinui connections. If you’ve been to Sydney (or almost anywhere, really), you probably already know that if you get off a plane and there’s a train to take you where you want to go, you’ll use it.

And we now know a train connection would not be more expensive than a tramline. But it still has that wretched BCR. Is it as bad as it seems?

In June last year AT received an analysis by Jacobs Consultancy, titled “South-western Multi-modal Airport Rapid Transit”, or SMART. Yes, what a clever name.

In the SMART analysis, trams had the advantage because construction would be easier and because the Dominion Rd tram route had a far bigger “catchment” than any train route: more people living or working nearby means more people likely to use the service.

But SMART also made a recommendation of critical importance: it said the project should not be considered in isolation but has to function well within the overall Auckland public transport network.

Cameron Pitches from the lobby group Campaign for Better Transport (CBT) picked up on that in a follow-up submission to the AT board. Pitches is an advocate for a train link. He said SMART had ignored its own advice because it had not allowed that trains on other lines would intersect with an airport line.

This was because SMART followed a “single seat” philosophy. This is the idea that when you get on a service you sit down once and ride all the way. You don’t transfer.

Pitches said it was wrong to expect that people living out along the western line, say, would not use the train. In his view, people will be prepared to transfer.

He made several other points. SMART had included costs that would be incurred anyway, like those for upgrading the level crossings. SMART also overlooked the fact that a rail line to the airport through Otahuhu would allow passengers wanting to go south to transfer at that point.

Importantly, he said SMART had exaggerated the likely travel times on Dominion Rd: 80km/hour? He didn’t think so. Pitches wants a tramline built on Dominion Rd, but he doesn’t see it as justification for a service to the airport: in his view, Dominion Rd trams will be slow and primarily have a local function.

Airport passengers, he believes, will be more likely to take a train to Onehunga or Puhinui, if a fast connection from either is developed. He says building that fast connection on a grade separated route is the key.

Ben Ross, from the group Talking Southern Auckland, argues that while the general catchment for a tramline on Dominion Rd is bigger, the catchment of people who work in and around the airport is bigger to the south and east, in the areas of Otahuhu and Manukau, currently served by rail, and out to Botany, which is currently served by no rapid transit at all.

For all these reasons, the Campaign for Better Transport and others believe the case against trains is still far from clear.

Nevertheless, AT has adopted the reasoning in the SMART report and strongly supports trams.

How good are trams?

The lobby group Greater Auckland, meanwhile, is with AT on this. GA is the organisation formerly known as the Transport Blog and as far as they are concerned, trams are the future.

We’re not talking about those stately wooden glories tootling around with 30 or 40 people on board. AT anticipates two-unit trams with each unit carrying 225 people, and Matt Lowrie at GA says three-unit trams are also possible. Modern trams can go faster than 100km/hour, which will be helped by “grade separation” on much of the line: the trams will be completely separate from pedestrians and other vehicles.

GA is the outfit behind the Congestion Free Network (CFN 2.0) which I wrote about here.

They propose two tram routes for the city, one from Orewa in the north all the way to the airport; the other from the northwest into the centre and then up to Takapuna. With trams running on both routes, both ways, every five minutes at peak times, they will have a combined capacity of 32,000 people per hour.

It’s nearly as many as the 36,000 per hour capacity of the rail tunnels (city rail link, or CRL). “Each of the two lines,” says Lowrie, “would be capable of carrying more people every day than our entire rail network does right now.”

This is important because the CRL isn’t an endless tunnel into which AT can just throw passengers. It will be at capacity not long after it opens. Trams have the virtue of adding capacity to the current network, because they have their own tracks. Whereas trains to the airport would extend the network but would not allow it to carry more people – at least, not through the middle of town and out the other side.

The map of the CFN shows how important this is: the orange and blue lines are trams, converging in the central city and running on the road surface up Queen St. The red and green routes are trains using the CRL tunnels.

As for Pitches’ comments about the connectivity of trains, they apply just as much to trams and trains.

Get used to the transfer

As SMART correctly noted, an essential feature of transport planning is to ask how each part fits the whole. Getting people from downtown to the airport is one thing, but what about people in Takapuna and Titirangi? St Heliers and Silverdale? How does the airport line function as part of the larger network?

A key feature of the CFN is that it accepts many passengers will have to transfer, so it offers a system where most people will need to do that only once. This is achieved by establishing that central north-south tramline as a spine (Orewa to airport), with all other routes linking to it or crossing it at least once.

There are some big station hubs: Britomart and Aotea/Queen St both have five routes passing through; Karangahape Rd and Ellerslie have four. Stations at Newmarket, Panmure, Otahuhu, Puhinui, Onehunga, Onewa and Constellation all have three.

And most of those have a mixture of trams and trains. The trams, says the CFN, represent “a 90-kilometre light-rail system… across two main lines that extends rail-based congestion-free transport to the northwest, the North Shore, the central isthmus and the airport. These are not ‘dinky trams’, but rather a grunty core part of the overall network.”

The CFN also says that with the proposed growth in new greenfields areas to the north and northwest, “ensuring a strong commitment to early investment in these areas is critical to their future urban form, creating transit-oriented developments that avoid the growth mistakes Auckland has made in the past”.

In other words, for the city to grow in a well-planned way, trams offer greater capacity and opportunity.

What are the key differences?

There’s no real cost difference. There’s no real time difference, either. Most analysts believe both trams and trains will take around 40-45 minutes to run between Britomart and the airport. Mind you, the Campaign for Better Transport doesn’t accept this. They believe the Dominion Rd route for trams will take about an hour.

The big difference is in the degree of future proofing offered by each option. Because rail tracks through the inner city will be at capacity soon after the CRL tunnels are opened, they’re not big on this. Those tunnels will allow trains to run more frequently on all the existing lines, which will double their capacity. And double is great.

But only double? It’s not great enough. Capacity on the CRL will be 36,000 people an hour – but we gained that many new Aucklanders last year alone. The CRL is vital to meet existing needs but it won’t future proof transport into and through the city. Trains to the airport, therefore, are not likely to be part of a future-oriented solution for Auckland’s traffic woes.

As Matt Lowrie says, we will soon need another “corridor” through the centre. Trams up Queen St provide that corridor.

As for the catchment issue, Ben Ross is right that the workers of the south and east need to be catered for. While he favours the train lines doing most of the work, he’s keen on trams from the airport to Manukau, intersecting with the Southern and Eastern Lines at Puhinui to form an interchange, and up to Botany, where they would eventually connect to trams heading for Panmure Station via Pakuranga.

Ross would like to see the Botany Line built as a Sky Train as it passes through Manukau City Centre.

What about buses?

Transport minister Simon Bridges and the NZ Transport Agency reckon an “advanced bus solution” could well do the trick for now. There’s a superficial appeal: with a pricetag of $1.4 billion it’s cheaper than trams or trains, and as with the Northern Busway, dedicated busways can be converted to tramlines later.

But in terms of getting from the city centre to the airport, the advanced bus “solution” has limited value. Building it necessarily means delaying the trams, so its benefits longer-term are compromised. When it does come time to upgrade, all the extra costs will kick in anyway.

Building a tramline from the city centre to the airport will take years, and crossing to the shore and heading further north will take even longer. It will be done in stages, so why not start stage one now?

That would be the city centre to Dominion Rd. As Matt Lowrie says, if AT can get trams running efficiently down Dominion Rd, a lot of the worries about how good a tram service could be will fade away.

Further complicating matters, the SMART report proposed ordinary “bus lanes” starting at the Wellesley St underpass beneath Symonds St, running up Symonds St, down Khyber Pass and then along Manukau Rd to Onehunga, before converting to a dedicated busway on SH20/20A. It noted, apparently without irony, that there would probably be major problems gaining the necessary consents. It’s hard to think of anything good about that proposal.

NZTA has commissioned an independent report on the bus option but it’s not available yet. Already, though, the well-connected political commentator Richard Harman has reported that officials in Wellington are “not so convinced” the busway can be built for the quoted figure.

Not that buses should be out of the picture. Patrick Reynolds of the Congestion Free Network, Cameron Pitches of the Campaign for Better Transport and Ben Ross of Talking Southern Auckland all suggest that a dedicated busway from Manukau through Puhinui to the airport will work as a good self-contained early step.

They say this would make it easy to get to the airport by catching a train from Britomart to Puhinui, which is on both the Southern and Eastern Lines, and transferring there to the fast bus to the airport. Pitches: “40-45 minutes for the airport run at peak should be an easy goal here.”

He suggests that anyone wanting to win the Botany or Pakuranga electorates in the September election would be stupid not to endorse this.

The CFN itself contains four advanced bus routes, including that one mentioned by Reynolds, although in the plan it extends all the way to Botany. In all cases the CFN allows that a future upgrade might be warranted, but for the next few decades at least, it suggests those upgrades will be less important than its other proposals.

A vital element of the CFN’s bus routes is that none of them end in the city centre. In fact, none of the CFN’s routes, for any mode, end in town: they all travel through and on to somewhere else.

Who supports what?

As it announced in the Mt Roskill by-election, the Labour Party wants trams to run down Dominion Rd to Mt Roskill. Onwards to the airport would follow. The Green Party wants the same. The lobby group Greater Auckland definitely wants trams.

The Campaign for Better Transport, on the other hand, does not think the case against trains has yet been convincingly made. Cr Mike Lee has long been an advocate for trains.

Auckland Transport wants trams: its soon-to-retire CEO David Warburton is a staunch supporter, as is the board chair, Lester Levy. The mayor wants trams. The council hasn’t decided. The government wants buses that could one day give way to trams.

What’s next?

Transport planning feels like a dam that’s about to break, and the water, when it floods through, is nothing less than evidence-driven good sense. It’s been known since 1990 that building roads creates more traffic. There’s even a name for it: the Lewis-Mogridge Position, named for the people who discovered it.

It goes like this: traffic expands to fill the available road space.

Three things should happen now.

- AT threw down the gauntlet to the governing body of council at the end of 2015 when it declared itself in favour of trams. The council has still not adopted a position. It needs to do that soon.

- The government has to rethink its transport priorities. Auckland traffic congestion will continue to get worse until it drops the roads focus and makes a serious commitment to using trams and/or trains to take the pressure off the roads.

- The government has to rethink its approach to funding. Certainly they should negotiate hard with council: both parties have a duty to act wisely with the public money they are in charge of. But Auckland’s ability to function is being undermined by cheap election politicking and that is unconscionable. Finance minister Steven Joyce’s first budget is due on May 25. He has already signalled he will reveal the general extent of the government’s financial commitment to the City Rail Link, but he needs to do more than that. Will he reinvent himself as the Champion of Trams? That doesn’t seem likely, but stranger things have happened.

Trams or trains? Trams offer better future proofing because they will build better network capacity, which is especially critical for all the routes running through the central city. They also have a stronger business case.

Those are the critical issues that make them the better option. The design and build process will go in stages but it needs to start now.

Maybe we should call them super trams. Fit for a super city.

The Spinoff Auckland is sponsored by Heart of the City, the business association dedicated to the growth of downtown Auckland as a vibrant centre for entertainment, retail, hospitality and business.