Twenty-one years after Steph Martin’s mother was killed in a road crash, she reflects on what’s been happening on New Zealand’s roads.

Last year, 378 people died in road crashes – more than one life lost per day.

Of those, 53 were under 20, and 16 hadn’t even reached the age of 15 – too young to even get their learner licence.

Steph Martin was 18 when her mother Gaynor died. She shakes her head as she describes the deep heartache associated with those raw statistics.

“For the families involved in that, it’s a lifelong trauma. It’s permanent and it’s intergenerational – my kids are raised with a story of a dead grandmother who was killed by someone,” she says.

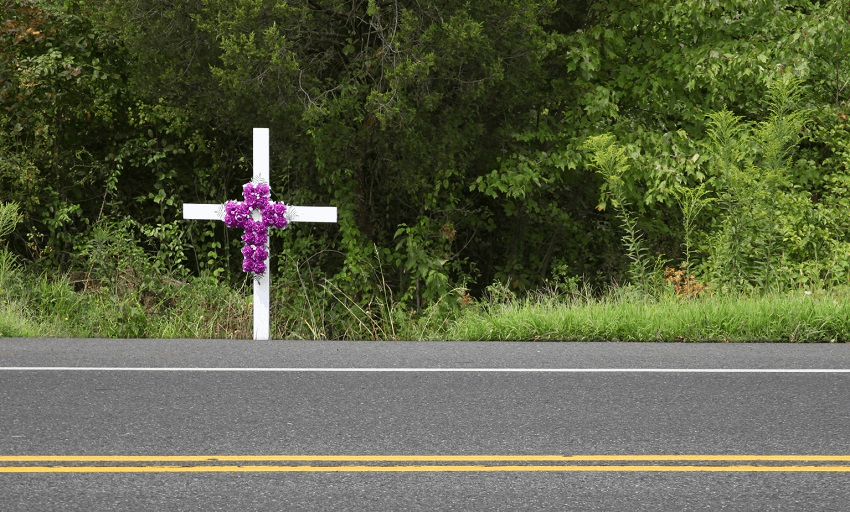

Gaynor, Martin’s mother, was with her partner Max Corkill on his motorcycle when the pair were hit and killed by a speeding car that had crossed the centreline outside of New Plymouth on January 20, 1998. Corkill was one half of the much-loved cat and rider duo ‘Max and Rastus’ made famous through Bell Tea television commercials and their advocacy work for animal rights.

For Martin, the memory and impact of that day have informed her decisions around driving, and safer road habits ever since. She’s now watching her 17-year-old daughter learn how to drive, and she’s a strong advocate for measures which can lower the road toll and prevent further harm and trauma caused by road crashes. One of those measures includes reducing the speed limit on dangerous roads – an Auckland Transport proposal currently up for public consultation in the city.

“As far as I can recall, my mum died instantly and Max died within some period of time – I would say less than half an hour,” she says of the crash.

They were heading north from New Plymouth. As they went around a right-hand bend a car coming from the other direction, travelling too fast, crossed the centre line.

“The driver was already disqualified from previous offences. He also had passengers, which he shouldn’t have had. He also had a child in the car, which he definitely shouldn’t have had. He had this massive driving history of harm, he was also under the influence,” Martin recalls.

“They really had no chance.”

Over the years, she’s observed how the trauma from her mother’s death has impacted her in different ways. She didn’t start driving until she was in her mid-20s.

“I didn’t want a licence after my mum died,” Martin says. “I didn’t want the responsibility. I thought it could happen to anyone and you need to know that you’re a good asset on the road, not a bad one.”

“And when I did get it I took it very seriously. I still take it very seriously. I take it as a complete honour that I get to get in behind the wheel of a car and that I’m sharing the road with other humans who are important. You can’t take that lightly.”

Martin, a Pukekohe local who runs the Goodness Grocer with her husband, smiles when she describes how vigilant she is on the roads. With her own daughter, Olivia, she’s particularly “vocal” in her message around driving responsibly.

“I just don’t want to ever be in a position where somebody has died because I’ve just checked my phone, or that I was in too much of a rush or that I didn’t sleep enough. I consciously don’t want to be that person.”

As part of reinforcing positive driving behaviour, Martin teamed up with local police over the summer to reward people driving well when they passed through roadside alcohol stops. To facilitate the summer stops, she contacted suppliers of her store asking whether they would want to contribute products towards a project which rewarded positive driving habits, like zero alcohol consumption and wearing safety belts.

“Every single company I asked said yes, and almost every single company wrote back with a personal story that they had actually suffered from a car crash or that [someone they knew] died, which is just so sad.

“I had the idea of writing a thank you note to good drivers, about how grateful I was they were taking their responsibility seriously… and we gave out all these free gifts. We handed out stuff out to about 500 people – it was great.”

For Martin, her attitude to road safety is clear: “It’s the idea that if everybody is going a little bit slower – even if it doesn’t bring the crash rate down – it brings the severity and deaths down, [and] that’s a win.”

In her mother’s death, speed was one of the factors, and perhaps if the driver hadn’t been going so fast, things may have been different.

“It’s a powerful thing to kill a person. You can’t take a life and then walk away from that. If the road toll can be lower by people driving a little bit less fast, and I could have my mother, of course, I would take that.”

Alanna Howard, service coordinator at Victim’s Support Counties Manukau, has more than 10 years experience dealing with families whose loved ones have been killed in road crashes. Like Martin, she sees many of them repeatedly question the circumstances that led to the death of their loved one.

“The ‘what ifs’ are huge,” she says. “They’ll go through questions like, what if we’d left half an hour earlier, what if we hadn’t gone that way – it’s just a multitude of what ifs.”

After dealing with 140 mainly rural fatal crashes, Howard believes a lower speed limit on rural roads would be especially useful. She notes that while there are often multiple factors involved (including driver intoxication), any change that could lessen the “hundreds dead” at the end of the year would be welcome.

She’s seen the devastating long term consequences of our road toll and the effects it has on survivors beyond emotional trauma. In addition to dealing with grief and trauma, she’s observed many people suddenly having to make arrangements to manage the loss of an income from their household and the ongoing psychological support required.

“Often, after the funeral, it’s usually at that point when family members start going back home, that support is needed quite intensely. That may involve facilitating grief counselling, or dealing with ACC.”

Further north in Auckland, cyclist Bruce Jarvis has a slightly different story to tell and explains why he is currently in a cast.

Jarvis was hit by a car coming off the north-western motorway on Great North Rd in Grey Lynn on January 28. At the time, he was about four minutes into a morning ride with his partner. The pair were heading towards the north-western cycleway from their home.

Footage from a street camera shows a white station wagon failing to stop at a give way sign. Jarvis is then knocked off his bike as the car passes him. His right-hand takes most of the impact and he’s lucky to get off without major injury.

“Luckily, I was going a certain speed and they were going a certain speed so the actual speed of collision wasn’t that high. If the car had been doing 50 km/h, we wouldn’t be having this conversation – it would have been ugly,” he says.

As a result of the crash, Jarvis’s right hand has a 3 cm screw holding the broken bones in place. While he’s expected to make a full recovery and return to his bike eventually, Jarvis says the crash highlights the importance of a 30 km/h speed limit at places like Great North Road.

“I had hand surgery and I’ve got a cast and I was back to work relatively quickly. I’m not complaining because I’m very, very lucky – it’s more annoying than anything. But, the whole view I’m putting forward is that we should be making the road safe for everyone, and everyone is safer at lower speeds.”

Jarvis, a group manager at Callaghan Innovation, believes some drivers need a more updated outlook on road safety.

“We’ve kind of got this mentality now that unless you’re in full flashing lights and dressed up like a gladiator, then you shouldn’t be on the road. But that’s the wrong mindset. The whole view I’m putting forward is that safety should be paramount for all road users. Unfortunately, there’s still a segment who think the road is for them only and they feel entitled to go as fast as they can.”

Ideally, all roads would be have dedicated cycle lanes and automated vehicles, removing human error, Jarvis says dryly.

“But that’s 10, 15 years away. Lowering the speed limit is one tool, but it can be done now, and it’s a relatively easy fix.”