Extract: In a new book about censored letters in New Zealand, the author tells the strange story of a German woman who dressed as a man and may have established a “lesbian network”.

Letter from Katherine Early to Hjelmar Dannevill, November 1915

I don’t know whether it will be possible to see you again, I sincerely hope it will for I never wanted you so much as now, but if not please let me say once more from my deepest heart “thank you” for all you have done for me… I shall be a better woman for having had the joy of knowing you and coming into contact with the uplifting influence of your personality.

One last favour I would like to ask and if you love me please grant me this, a picture of yourself.

My very much love goes out to you always.

Letter from “Helene” to Hjelmar Dannevill, May 1917

Oh my Hjelmar I do want you so, I must let my heart’s love flow out to you in writing it will relieve me. All today you have been more than usually in my mind, and life without you is difficult. How I long to go to you! Perhaps tonight you may be thinking of me, you may be near me in the spirit, as I believe you often are, or I could not at other times feel so content, so happy, so secure in the possession of that treasure.

But tonight, though I am fighting against the boredom of everything I feel so restless, so aching for a sight of you. Are you very tired this weekend? Are you longing for the great blue expanses of the ocean? For the illimitable distances of the desert? Would that I could give you your heart’s desire, whatever it may be!

***

Sir John Salmond, author of the War Regulations, opened the secret dossier titled “Dr Von Dannevill” and read the memorandum from New Zealand’s chief censor, Colonel Gibbon: “I should be glad of your advice as to what action, if any, should be taken in regard to this person.”

This is what they knew: Hjelmar Dannevill had arrived in Wellington in 1911 with an extraordinary past – if what she said was true. Accused as a German spy by an anonymous informant in October 1914, she claimed she was Danish but her credentials were hazy at best. She wore men’s clothing. She preferred the company of women. She appeared to hold sway over all who knew her. And she managed a mysterious health home on Wellington’s Miramar Peninsula whose patients often refused to talk to police.

Salmond looked over the handwritten reports and took stock. It was May 1917. Although the peak of anti-German hysteria had passed, an underlying prejudice against anything German was ever- present – not to mention the dominant social views on femininity. For not only was Hjelmar’s nationality suspect, so was her gender.

According to Superintendent John Ellison’s report, in March 1911 Hjelmar had come to him and asked for permission to wear men’s clothing: “She mentioned that someone had accused her of being a man dressed as a woman, and desired me to give her a memorandum to show that I believed her or knew her to be a woman.”

Ellison refused. “Of course I declined and told her very plainly why I could not do so and that I had doubts as well.” Even after Hjelmar allowed herself to be examined by a woman who was present, Ellison still had a suspicion “that Dannevill is a male and an imposter”.

Even more disturbing to Salmond was the report of Detective Sergeant Rawle, who had caught wind of an incident involving Hjelmar and the Lahmann Health Home where she worked. A disgruntled vicar named Edward Bond claimed that his wife, Mary Blanche Oliphant Bond, had been lured away by Hjelmar. Mary was the youngest daughter of John Tiffin Stewart, a well-known civil engineer and surveyor, and Frances Ann Stewart, a social activist and the first woman in New Zealand to sit on a hospital board. Suffering from a severe nervous breakdown, Mary had moved to the home on her doctor’s advice in 1915. But eight months later she no longer wanted anything to do with her husband; whenever he visited Mary refused to see him.

Salmond must have read these reports with horror. Here was evidence of a masculine, cross-dressing woman meddling with a man’s wife and shamelessly subverting gender norms. Not only that, she was a suspected enemy alien. Her actions seemed to fit the prevailing anti-German attitude and its vision of barbarians vandalising the fruits of European civilisation. For the brisk, obdurate Salmond, this case combined the worst of both prejudices.

“There is grave ground for suspicion that this person is a mischievous and dangerous imposter,” he wrote, someone “who ought in the public interest to be interned during the war. Her identity is wholly mysterious.” Salmond was apparently unsure “whether she is a man or a woman. She is very masculine in appearance and habits. There is much reason to suspect that she may be a man masquerading as a woman.”

His advice to Gibbon and O’Donovan was to arrest Dr von Dannevill as a dangerous alien, find out her sex, nationality and history, and then consider the case further. Until then she was to be interned at Somes Island.

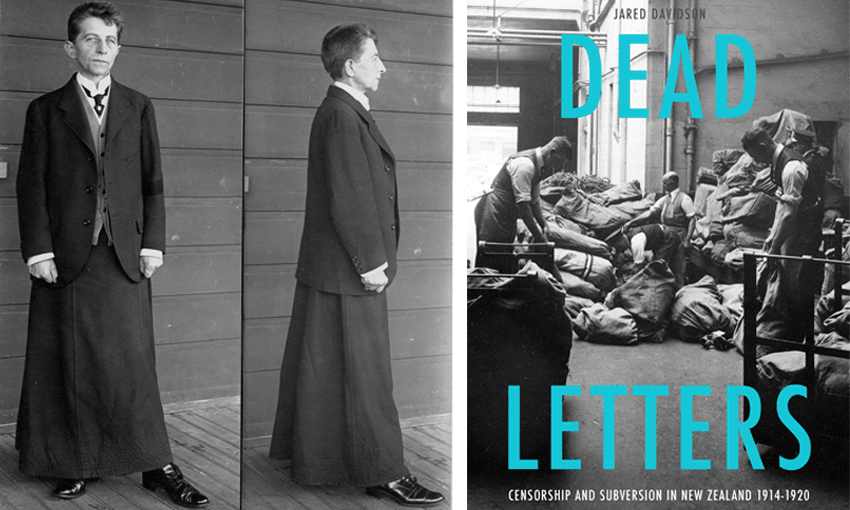

On May 21, 1917, Police Matron Beck and Detectives Boddam and Cox left the tram and made their way towards the Lahmann Home’s impressive entrance. Hjelmar Dannevill answered the door. She was dressed in her distinctive style – collar, shirt and waistcoat, an immaculately tailored jacket adorned with a pocket watch, and a long skirt that reached to her leather boots. Hjelmar was known to have smoked a pipe, but did not do so on this occasion. Once inside, the detectives found a picturesque foyer with dark red walls and stained wooden panels. Great bowls of scarlet gladioli and vases of feathery-looking ixia dotted the space, and Boddam noted the staircase that led to the home’s second floor and its exterior balconies.

“After informing her who we were,” wrote Boddam, “I requested her to accompany us at once to the office of the Commissioner of Police, who desired to interview her.” The police confiscated a bag of letters, books and other papers. Hjelmar went quietly, saving Boddam the task of using the warrant for her arrest.

As Hjelmar boarded the tram surrounded by police she must have pondered her sudden change in fortune. Five years earlier she and Dr Huntley had been hosts to over 200 women of high society. The December 1912 opening of the Lahmann Home was a grand affair. Guests toured the grounds with cups of tea accompanied by the music of the Miramar Band, while those inside were treated to performances on the grand piano.

The Miramar retreat offered a natural care system of massage, hydrotherapy, a vegetarian diet and plenty of fresh air. Lahmann himself was a staunch advocate of animal rights, and refused to use them in laboratory experiments. The home was probably equipped with air baths as per Lahmann’s teachings. It also provided less “natural” cures such as electrical therapy (a form of shock treatment, which some brave guests were “treated” to on open days).

Hjelmar and the Lahmann Home seem to have been an accepted part of the Wellington community. She hosted a number of talks, known as “At Homes”, where women gathered at the retreat for music and more tea. “Dr Edith Huntley wore a dress of shot violet and green velvet with trimming to match. Dr von Dannevill was in navy blue,” reported the social page of one weekly. Apparently no one cared about – or cared to mention – Hjelmar’s masculine attire.

By 1917 attitudes against difference had hardened and not even Hjelmar’s high-society friends could save her from the police, spurred on by Reverend Edward Bond’s complaints. She now found herself at the Lambton Quay Police Station and face-to-face with the commissioner of police.

O’Donovan was clearly as much thrown by her gender variance as Ellison and Salmond had been, and repeatedly dwelt on it during the interrogation. “Were you dressed as you are now?” he asked.

“I was not dressed in the same clothing.”

“You were wearing a man’s hat and coat and an ordinary vest and collar of a man?”

“Yes I think so, and a skirt.”

“Did any question arise between you and Mr Ellison as regards whether you were a man or a woman?”

“He said there was no objections to my wearing men’s clothing so long as he knew I was a woman.”

O’Donovan asked Hjelmer if she would submit to a medical examination, and she agreed. “I hereby certify that I have this day examined Dr HW Dannevill, and that the anatomical configuration shows that she is of the female sex” reads the dispassionate medical note.

*

The case of Hjelmar Dannevill is remarkable for many reasons, and many elements in it remain obscure. Are these letters evidence of a lesbian network? Was Hjelmar the “lady husband” of Mary? And why did she dress the way she did – was it linked to sexual desire, for ease of travel, an attempt at being a masterless woman, or simply because she wanted to?

Whatever the reasons, it is clear Hjelmar’s overall relationship orientation was to women, and that her companionship with Mary (and her child) was obviously more than just a therapist/client one. Her multiple friendships, her class, education, and profession all suggest that Hjelmar was able to make lesbian expression the organising principle of her life.

Less than a year after her internment, NZ Truth reported that she had been spotted in Timaru (was she visiting Helene?) The Anti-German League, which had also hounded Marie Weitzel, took on the case and requested that the Defence Department banish her from the town.

It’s not clear whether they were successful in their modern-day witch-hunt, or whether she simply returned to the Lahmann Home. That year the military finally accepted Dr Huntley’s offer to turn the retreat into a convalescent home for returning soldiers. It did not last long – the military cancelled its lease in March 1920.

The Home was eventually bought by the Education Department and became the Miramar Girls’ Home (the building still stands at 8 Weka Street, opposite Weta Studios). By this time Hjelmar had left the country. And with her was her companion of five years, Mary Bond.

Local newspaper reports of Hjelmar’s movements end in May 1920, when she and Mary left Sydney for Suva. Eventually they settled together in San Francisco – Hjelmar dropped the ‘von’ from her name, made her living as a physician and remained a companion of Mary and her three children. In a city that would later become famous for its queer pride, Hjelmar fought for and won the right to wear men’s clothing in public.

Dead Letters: Censorship and subversion in New Zealand 1914-1920 by Jared Davidson (Otago University Press, $35) is available at Unity Books.