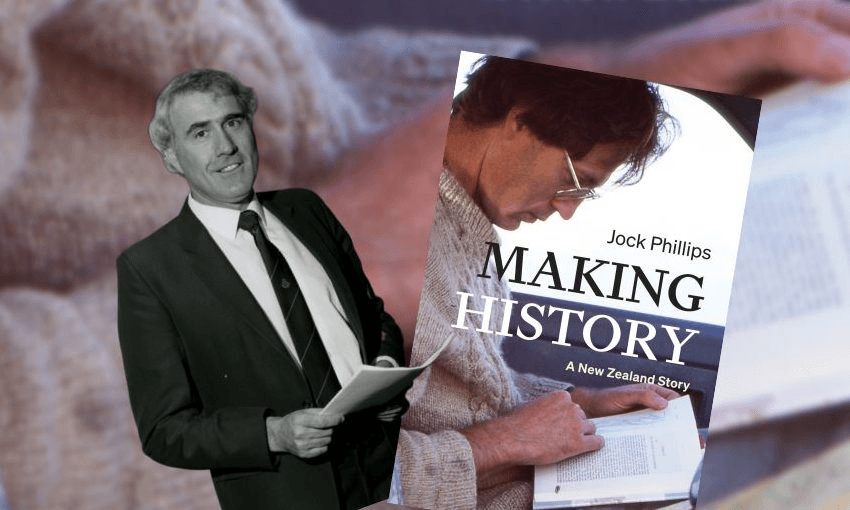

On the publication of a new memoir, former prime minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer pays tribute to historian Jock Phillips. Branded a dangerous, trendy lefty by Muldoon, Phillips has for many decades kept his intellectual navigation shining brightly.

Making History – A New Zealand Story is a book that contains significant insights into New Zealand’s intellectual history and life on these islands. It marks an important way point in our development towards a nation with a mature sense of self confidence and an imprint of identity. It is a book that tells us how we are changing.

Historians have much to teach us, but few of them have taught us as much as Jock Phillips in his splendidly varied and rich career.

To me a memoir is a statement from a person who has spent a long time thinking, evolving, and gathering experience.

Writing a memoir signals the author has now arrived at the point where he or she can make confident insights into what is really important. So he can make sense of his life.

Jock is fascinated by what New Zealand was compared to what it has become. The material about his parents tells the reader much about the remarkable shift in focus that New Zealand has had in Jock’s lifetime.

Jock’s father was Professor Neville Phillips of the University of Canterbury, appointed to the Chair of History and Political Science in 1949 and made Vice Chancellor in 1966.

Although born in New Zealand, Neville did not enjoy a privileged childhood. His family origins were among the Jewish community in London. Neville wrote an excellent MA thesis and received a scholarship to Oxford. After a year there, war broke out and he joined the British army.

Meanwhile he had fallen in love with fellow Canterbury student Pauline Palmer, who became Jock’s mother. She came from a sheep station in the Hawkes Bay: a background which Jock says, “reinforced the English gentry ideal”. The enchanting picture Jock paints of the Hawkes Bay rural squattocracy is loving but acutely aware of the foundations upon which it was built.

Neville was an extremely fine lecturer, the book tells us. I can endorse that, having heard him once on a visit to the university when he was speaking about Edmund Burke. The remarkable thing about Professor Phillips was that he revelled in English culture and took only a limited interest in New Zealand culture.

After he retired as vice chancellor of the University of Canterbury he and his wife lived in England and stayed there. As Jock puts it: “a cultured life in the home counties of England was satisfaction enough.”

Comparing Jock’s career with that of his father, you could not say it was a case of like father like son. Their mutual love of history led to very divergent paths. Jock went to Cathedral Grammar School for his primary education, then to Christ’s College, followed by Victoria University of Wellington and Harvard, where he did a PhD in History.

Probably it was the decision to go to Wellington that began his deviation from the path of conservative rectitude that characterised the intellectual life of the Christchurch establishment when he was growing up.

His account of his studies at Victoria display some impatience at the things that were taught and how they were taught.

At Harvard his mind was lit up. There was a lot going on in the United States of a radical character during his time there.

He says:

Politics, gender, the counter-culture – they all moved me and took me some distance from the background of which I’d grown up. Inevitably, this led me into conflict with my parents, if rebellions of the period were anything, they were primarily a generational revolt.

Jock found, as many others have before him, that New Zealand university training in written expression was certainly superior to that received by American students. On the other hand, the oral facility of New Zealand students was much less.

Jock’s training at Harvard was rigorous and stood him in good stead when he returned to New Zealand in 1973.

At Victoria University Jock taught mainly American history and he became impatient with the deeply conservative curriculum. He was a rebel in the department and a little demoralised.

Jock became what Sir Robert Muldoon used to call a dangerous, trendy lefty from Victoria University.

He soon found a public voice writing editorials in The Listener once a month.

Although he was teaching American history, Jock became more interested in New Zealand historical research. He wrote a memorable book on stained glass windows, and another on Kiwi men, A Man’s Country? These were outside the mainstream of academic history.

In 1983, Jock set up the Stout Centre which has made and continues to make a substantial contribution to both Victoria University and to wider New Zealand. It attempted to rectify the lack of institutional support for research into local topics.

Jock’s work there on the military side of New Zealand led to the book The Great Adventure about the first world war. He had set up a way of exploring New Zealand culture.

As Jock says: “I’d broken with the cultural traditions of my upbringing, in exploring the society and culture of my own country, I’d found my niche in life.”

Jock’s next berth was as chief historian of the Historical branch of the Department of Internal Affairs.

This was a job to which he was guided by Dr Michael Bassett, the then Minister of Internal Affairs, whom he already knew as a fellow historian. It was through this connection that Jock became a real Wellington operator at the higher levels of the New Zealand public service.

He regarded as his quest New Zealand’s need for cultural and social history. And they weren’t doing that in the branch then. He transformed the position and had some very interesting bureaucratic struggles with the top level of management in the Department. Between 1990 and 2000 the branch “produced 67 books, averaging over six a year”, encouraging the growth of public interest in New Zealand history.

From late-1993 to late-1997 Jock had a great deal to do with projects for exhibitions in Te Papa. This work exposed him to the culture of the tangata whenua in ways that had a permanent effect on his outlook.

It dawned on him as well that if history was to be anything, it should be taken to the people so that they could understand it.

In a “sojourn on the dark side”, he became general manager of heritage in the Department of Internal Affairs. All sorts of bureaucratic battles were fought especially with Archives. It was a mark of Jock’s ability as a bureaucratic infighter that he managed to retain good relations on all sides.

Then came an exciting new phase in Jock’s life. As well as being elected to the Victoria University Council, he was in charge of creating and developing Te Ara the on-line encyclopedia from 2002 until 2014. This was ground-breaking and a tremendous achievement.

Jock regarded it as “the first port-of-call for reliable information about New Zealand”. It was to be a gateway to the cultural treasures of the nation.

In a life well-lived, Jock Phillips has kept his intellectual navigation shining brightly.

He is endlessly curious and innovative, a builder of New Zealand’s history in the widest sense.

The piece above is based on a speech Sir Geoffrey delivered at the Unity Books launch of Jock Phillips’ memoir On Making History – A New Zealand Story, published by Auckland University Press, and available at Unity Books.