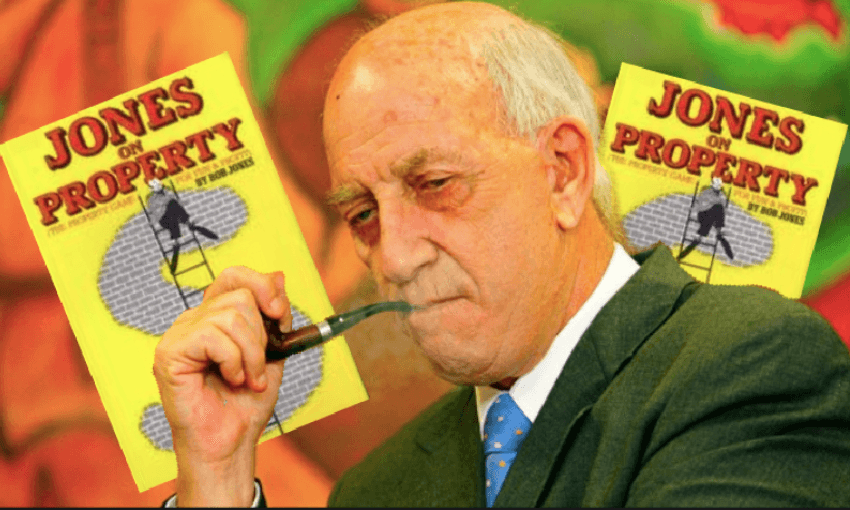

Danyl Mclauchlan reads the 1977 book Bob Jones on Property, and wonders about the role it played in creating today’s distorted housing market.

Sir Bob Jones has been in the news a bit recently. In February he published a column in the NBR suggesting that Waitangi Day be abolished and replaced with “Maori Gratitude Day”, in which “Maori bring us breakfast in bed or weed our gardens, wash and polish our cars and so on, out of gratitude for existing.” NBR pulled the piece when a storm of social media outrage rose above the usual day-to-day torrent of social media outrage; defenders of Jones were duly outraged by the outrage, arguing that Jones was obviously not racist, that the piece was obviously a work of satire, and the column was obviously a celebration of free speech. Jones followed all this up by singling out two Māori women from his large number of critics and suing them for defamation. His admirers have yet to explain how this illustrates Sir Bob’s alleged devotion to free speech and non-racism.

Jones has been such a cliche – the absurdly rich old reactionary whining about things like bad grammar and lazy Māori and women drivers – for so many decades now it’s hard to imagine what an impact he had, what a transformational figure he was, way back in the day. Mid-20th century New Zealand was a stultifyingly dull, conformist place; the economy and business sectors were dominated by farming, a handful of wealthy, powerful dynastic families and a legendarily inert, bureaucratic public service.

Jones was this working-class kid from Naenae who boxed his way through university and became a multi-millionaire by his mid-twenties, an outrageous self-made tycoon tearing his way through a grey, quasi-feudal economy, an iconoclast who relentlessly mocked the pillars of society: politicians, company heads, public servants, the underperforming share-market. He attacked the National Party as socialists; hosted a radio show advocating libertarianism and capitalism and gave seminars that contemporary accounts likened to evangelical revival meetings.

So when he published a how-to guide on property investment, tens of thousands of New Zealanders rushed out to buy it. And they’re still reading it! Jones’ first book is constantly checked out of the library.

“There’s always a demand for his stuff,” one second-hand bookstore proprietor told me, leading me through his store to the Bob Jones shelf. “I had someone in here just yesterday looking for Wimp Walloping.”

“Just don’t tell me he’s more popular than Lloyd Jones.”

“Good lord yes. Now, let’s see. We’ve got Punchlines, Wowser Wacking, Fighting Talk, something called Ogg . . . Not the property book though.”

I finally tracked it down through the website of a second-hand bookshop in Morrinsville: Bob Jones on Property, published all the way back in 1977.

It was perfectly timed. By the late 1970s a generation of baby-boomers had entered the workforce and, now that they had some money in the bank, they reconsidered the egalitarian values they formed when they came of age in the 60s. Instead of a sharing, non-materialistic society in which everyone was equal and cared for each other, wouldn’t it be better, they reasoned, to live in a world in which they personally were rich and had lots of nice stuff? Jones was there to show them how; to initiate them into the mysteries of capitalism and acquire the wealth of their dreams.

Well, sort of. Jones on Property reads less like a textbook or how-to manual and exactly like a sequence of Bob Jones columns, an artistic medium that has not changed in form or content even slightly in 40 years. There are many vague, often unlikely-sounding pub anecdotes (“There was once a true story in which a very correct English lady …”) in which Jones belittles his lifelong enemies: politicians, academics, unionists, women, lesser men who have jobs, or who own companies that aren’t property investment companies; all other humans, basically. There is some advice buried in there – but is it good advice? Could those who follow it become as wealthy as Jones?

Danny Kahneman’s famous formula for success is that it equals “talent plus luck”, while “extraordinary success equals a little more talent plus a lot more luck”. Very few business leaders are self-aware enough to grasp how coincidental and contingent their accomplishments are, which is why their books on wealth creation are almost universally worthless. There’s a section in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers in which Bill Gates articulates all the factors outside his control that lead to his early success; but Jones is not exactly Gates. He may have been a brilliant salesman and company director but those are hard things to teach in a book, especially a book this rich in digressive rants denouncing tax and socialism.

Jones has “three universal and inalienable golden rules” for property investment: “location, location and location”. Never mind that these are nouns, not rules; for a wild moment I wondered if Jones had invented “location, location, location,” he seems so proud of it. But no: a few seconds’ research revealed it was a common term as far back as the London property market in the mid-1920s. Then there’s “The Jones’ Principle”: “act only on your own terms”, which translates roughly as “only do things you want to do, with the intention of making a massive profit” and which he feels is comparable to Newton’s law of gravity, only slightly better.

Some of the tips are – in the smug light of hindsight – so terrible that I half-suspect Jones of deliberately misinforming his readership to gain a commercial advantage over potential competitors. There’s an entire chapter devoted to the unprofitable nature of land banking. Buying undeveloped property on the periphery of cities is also, he warns, a terrible investment (he prophesies that the world population in the 1970s is about to plateau and then decline). And stay away from listed property investment companies, warns the future head of Robert Jones Investments Ltd. But mostly the advice is generic, uncontroversial, cliched: find an investment that’s valued at much lower than the market value; get tenants that pay well and stay for a long time; accept sunk costs; business is cyclical; buy low, sell high.

There are three huge and crucial points in the book that aren’t meaningless, or flat-out wrong, which Jones returns to again and again. Firstly: property, of all the commercial sectors, has the lowest barrier to entry because banks loan larger sums of money to new investors to speculate on the property market than any other class of asset. Secondly: you can leverage that debt for greater profits at lower risk. And thirdly: the gains you make on that speculation don’t attract any tax. So the investor puts up 20%, the bank puts up 80%, the investor gets 100% of the gains and the tax department gets nothing.

Nowadays every middle-class New Zealander with an IQ over 80 understands that math, but back in the 70s this was revelatory stuff. Thousands followed Jones’ advice and poured their savings into property, and tens of thousands followed them, and hundreds of thousands followed them, borrowing from mostly Australian banks to buy our houses back and forth off each other at ever inflating prices.

Over 40 years later New Zealand is, as the international investment banks like to put it, a housing market with a small country attached; our residential stock alone is worth over a trillion dollars, almost ten times larger than the combined market capitalisation of the domestic share market; while families across the country are sleeping in garages and cars due to housing unaffordability. The state is scrambling – rather desperately – to try and fix a completely broken housing system. But if you followed Jones’ advice 40 years ago you definitely got rich, and can join him in congratulating yourself as a hero of capitalism.

There’s a problem there, though. Surprisingly little of the activity Jones endorses in his book counts as capitalism, at least as the economists and philosophers who championed the ideology conceive of it. The perfect investment property, Jones declares, is a factory because it’s just four walls and a roof; the company that leases it does all the work and pays you your rent, and you make money through no effort whatsoever! This maps almost perfectly onto a famous argument from Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations in which Smith divides the distribution of income in a capitalist economy into wages, profits and rent. Take a hypothetical factory: the capitalist owns an oven that bakes bricks, or a machine that makes pins; and keeps the surplus wealth after they’ve paid their workers and their rent, the rent being the unearned value that landlords extract from capitalists and workers.

Modern economists refer to this as rent-seeking. The worth of the landlord’s property is almost always largely derived from government infrastructure and services – proximity to roads, hospitals, schools, universities – and the titleholder adds little value in comparison. From this perspective, capitalism is about the mutual benefit between capital and labour. The rent-seeker who creates no wealth but merely leverages the value created by the state to expropriate the wealth of others is the enemy of capitalism.

Jones is bitterly aware that people regard property speculators like himself as parasites. Those people are just jealous socialists, he seethes, and the most abhorrent of them are those who suggest he should have to pay tax on the money he makes while doing no work and creating no value. It’s hard to think of a prominent right-wing or neoliberal economist who hasn’t advocated a land tax or a property tax or a tax on capital, specifically to prevent people like Jones sucking wealth out of the productive economy, but to his mind people like Smith, von Hayek, Friedman are just socialists, all of them socialists. Is it any coincidence, he demands, that when the communists seized control of China, landlords were seen as the great evil?

But by the end of the book he concludes, gloomily, that a tax on capital is probably inevitable. The socialists will eventually come for investment property income and when that happens the time will come to sell up and get out. As with so many of Jones’ predictions this did not come to pass. The tax-free status of property investment endures; when the OECD urged Michael Cullen to introduce a capital gains tax he instantly dismissed it as “political suicide”; Labour ruled it out yet again prior to the last election. Perhaps not coincidentally, New Zealand’s MPs have their own class of specially legislated private superannuation schemes where they can own property investments without disclosing them, and which are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer.

Towards the end of Capital in the Twenty First Century Thomas Piketty proposes a progressive tax on wealth as a way to make capitalist economies more meritocratic and productive. It would be zero or nominal for small businesses and typical homes but rise for higher amounts of wealth, and as I struggled to the end of Jones on Property in which the author fantasises about a property-owning revolution in which politicians are marched to the guillotine, I found myself fantasising about an asymptotic wealth tax that rose until, when you reached Jones’ level of affluence – about $750 million, according to some estimates – became downright confiscatory.

And on the day of its introduction, I daydreamed on, we could celebrate by having people like Jones, all our suddenly reduced property speculators and financiers, get up and mow the lawns and polish the cars of teachers and nurses and drivers and retail workers and office clerks: everyone who actually works for a living. I let the book fall to the table where the breeze ruffled the pages like an invisible hand, and dreamed about Parasite Gratitude Day.

The Spinoff Review of Books is proudly brought to you by Unity Books.