In his latest book, Fentanyl Inc., journalist Ben Westhoff (The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, Playboy, Vice etc) goes deep on the epidemic of ‘legal highs’, including the notorious, deadly fentanyl. There’s an extremely intense bit where he poses as a buyer and infiltrates a Chinese drug lab.

It was New Zealander Matt Bowden who invented the first legal highs. He’s always insisted he meant well; that he was trying to develop an alternative to the meth that had taken hold here and to which he had been addicted. In this extract from the book, Westhoff explains what happened after we banned that first generation of legal highs.

After New Zealand made BZP illegal in 2008, Matthew Bowden was frustrated. His pills had ushered in a drop in overdoses and violence in the local party culture but apparently to no avail. “There’d been no deaths, no lasting injuries, no real serious hospitalizations for people using the product as directed, but they decided to make it illegal,” he said. He worried the nightlife denizens would turn back to crystal meth.

To console himself, Bowden took some time off. He grew his hair out and, under the auspices of his glam rock alter ego, Starboy—wearing KISS-style face paint and steampunk accessories—started working on a new album. In 2010, however, a new drug called to him: fake marijuana.

Bowden was well aware of synthetic cannabinoids’ dubious safety reputation. Still, that didn’t deter him when, he said, he was approached about manufacturing new fake pot compounds. He figured he could do things differently. And so, as before when he was looking for a meth substitute, he focused on making a safer product, working with pharmacologists to try to find a less harmful synthetic cannabinoid. “We were creating hundreds of new [cannabinoid] molecules, working out which ones were going to be less toxic,” he said. The best ones they synthesized and patented.

He renewed his public-relations efforts, hiring a well-connected law firm, led by former New Zealand prime minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer, to help him persuade the government that the country needed a recreational-drugs industry that was required to do product testing, meet safety standards, and clearly label its offerings—not one that operated in the shadows.

Remarkably, politicians started listening. Before long, they even crafted a bill.

“Quite simply they will now have to do what any manufacturer of any product that is consumed or ingested already has to do—make sure it is safe,” argued Parliament member Peter Dunne, speaking in favor of the Psychoactive Substances Act of 2013, which would effectively legalize not just BZP but a host of other party drugs and synthetic cannabinoids as well, including the ones made by Bowden. This would be a completely unprecedented piece of legislation, moving New Zealand in the opposite direction from the rest of the Western world—which was making new drugs illegal as fast as it could.

New Zealand focused on these substances, instead of legalizing traditional ones like MDMA or marijuana, because the country’s hands were tied by the United Nations international drug-control treaties, which outlawed the most common recreational drugs and to which it is a signatory. An issue with the Psychoactive Substances Act was that none of these new drugs (including Bowden’s) had gone through clinical trials, and holding such trials would be extremely time-consuming. To address this, the law would permit new drugs that had previously been sold without incident to be grandfathered in.

It was an extremely complicated bill, one presented under the auspices of regulation, rather than legalization. Quite possibly not everyone in the New Zealand Parliament fully understood what he or she was voting on. When the results came in, on July 17, 2013, they were staggering: 119 to 1, in favor.

Legalization advocates rejoiced, as did Bowden. They were optimistic that this new law could show the world how to avoid an NPS crisis, by putting safety and control above prosecutions and imprisonment.

Sales were restricted to those over eighteen years of age. Pills couldn’t be sold in gas stations or grocery stores. And packages displayed warnings not to drive after consuming their contents. This was a mind-boggling policy shift. People around the world suddenly began paying attention to this small island country, best known to many for its sheep.

“New Zealand’s Designer Drug Law Draws Global Interest,” read a CBS News headline, noting that some British parliamentarians hoped to bring a similar policy to the United Kingdom. New Zealand’s government—which Bowden praised as “small and maneuverable”—was suddenly in the vanguard of progressive drug law. And it had Bowden to thank for it.

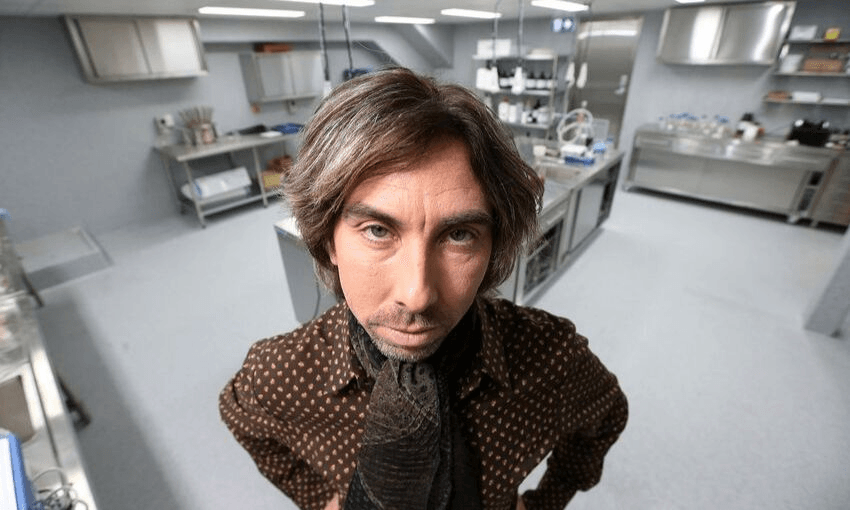

Though Bowden had been having his new products manufactured in China, he began to believe that his partners there weren’t keeping his new creations secret. And so he began building a lab of his own, in Auckland, which opened in 2013. It featured state-of-the-art equipment and, eventually, five employees. By his accounting, their work was a success. “Our products were not producing addictive behaviors or overdoses,” he said.

For Bowden, the dream he had pursued for more than a decade was finally coming true. Working out of his lab, he and his team manufactured large quantities of his party-pill meth and ecstasy replacements, as well as synthetic-cannabinoid alternatives to strains like Spice and K2, which were causing so much damage. He hadn’t made much money off his drugs previously, Bowden said, focusing instead on his goal to make safer products.

But eventually he decided it was time to cash in. After legalization, when the synthetic-cannabinoid profits really started to accumulate, he bought property—including a palatial house for his family in the lush countryside. In that moment, he seemed to have everything he could ever want; a loving wife selected by a divine matchmaker, a beautiful family, and a successful business doing something he felt proud of, grounded in utopian ideals and endorsed by the government.

But within a year Matt Bowden’s revolution went up in smoke. Public opinion quickly shifted against the now-legal drugs.

A combination of factors turned the tide. For one, not many stores applied to sell the drugs, perhaps because shop owners didn’t want to go through the cumbersome approval process. As a result, the few stores that did receive licenses sometimes had lines around the block, creating loitering masses who got high and created disturbances. “Imagine if you only had one liquor store in town. You would have a queue of people,” Bowden said. “So that’s what we had. There would be these big queues of people, smoking and getting a little wasted in the streets.”

The media began picking up on this problem, as well as the preponderance of emergency-room visits, and the fact that some were becoming addicted to the cannabinoids.

A controversy also began to erupt around the issue of animal testing, a critical component of drug development. Protests sprang up, which Bowden said led to the spread of misinformation: “Some were saying, ‘The party-pill guys want to kill our dogs!’” Bowden affirmed that he never, in fact, tested on dogs. He also claimed that when he began attempting to develop a safer alternative to alcohol, the beer, wine, and spirits lobbyists began campaigning against him.

And so, in 2014, an election year, New Zealand reversed course, revising the legalization bill to make the party pills and synthetic cannabinoid strains illegal. Some of the same lawmakers who had voted in favor of the legalization bill a year earlier now claimed not to have realized what they were endorsing. The drugs that had been grandfathered in were now un-grandfathered. Under the revised bill they could still win authorization for legal sale, but the revised bill also curtailed animal testing, which threw a wrench in the process. Effectively, it all but blocked the possibility of new drugs receiving approval.

“The immediate effect was that the industry was handed on a silver plate to the black market,” Bowden said. “All the manufacture standards, all the dosage control, it went out the window.”

After New Zealand’s legalization repeal, Matt Bowden still planned to try to bring his drugs, including BZP, up to code, but the collapse of the industry he had so heavily invested in left him financially obliterated.

Owing unpaid back taxes and other obligations that amounted to some NZ$3.6 million (US$2.4 million), he was forced, in May 2015, to liquidate his company. “I did make some mistakes,” he admitted. “I was sloppy with accounting back when we were a small company starting out.”

Unable to secure new loans, Bowden was locked out of his lab and lost his estate and other possessions, even the steampunk fashion line he had worked on with Kristi. According to a 2015 news report, the “fixed assets” of Bowden’s company, including “lab equipment, music equipment and the costume and prop hire branch of the business” were sold off for NZ$230,000—money that went to creditors. Broke and owing millions, Bowden faced the possibility of jail time over the unpaid back taxes, a criminal offense. And so he, his wife, and their two young children fled the country in 2015 and landed in Chang Mai, Thailand.

In July 2017, ten Auckland deaths were attributed to synthetic cannabinoids. The fatalities caused a national uproar. The country’s National Drug Intelligence Bureau soon released a report, placing blame on the Mongrel Mob—New Zealand’s biggest gang, known for extensive facial tattoos—for controlling much of the drug’s distribution. “It is believed they have started manufacturing their own product in order to increase and retain control of the supply chain,” wrote New Zealand news website Stuff. The worst fears of Bowden and others, who had hoped to bring synthetic cannabinoids into the light, were being realized. The strains associated with the Auckland fatalities were not the same ones that had been previously sold legally in New Zealand—they were much, much stronger. “Dose escalation is going crazy,” Bowden said.

By the end of 2018, more than fifty New Zealand fatalities had been tied to synthetic cannabinoids. The deaths prompted international news coverage. Most of the stories made only passing, if any, mention of New Zealand’s political experiment. Little analysis was undertaken to determine whether legalization—with workable safety testing and clear labeling—might have saved some of these lives. “The law was ruined over the animal testing BS,” Bowden said, noting that, because the law was changed, human beings were instead serving as the unwitting test subjects.

The scourge of deadly synthetic cannabinoids was by no means limited to New Zealand. Media reports of mass overdoses and “zombie” outbreaks began appearing across the United States—the same country where, in medical labs, many of the most potent strains were invented.

Fentanyl, Inc. by Ben Westhoff (Scribe, $40) is available at Unity Books.