An extract from Benjamin Kingsbury’s The Dark Island, about the history of the leprosy patient colony on Quail Island, in Lyttelton Harbour.

Books editor Catherine Woulfe writes: There are certain passages of Benjamin Kingsbury’s new book The Dark Island that make the reader wince and turn away. But then you turn back again, you can’t help it, it’s just such a great yarn.

With compassion, Kingsbury recounts the untold history of Quail Island in Lyttelton Harbour, and the treatment of leprosy patients – he never uses “lepers” – that were rounded up and exiled there in the early 1900s. Pine trees and pain, meals gingerly passed across no man’s land; what a life. What a death.

In this extract, he tells the story of a Pākehā man who showed up at Christchurch Hospital in the summer of 1906. He had terrible sores over his face and arms, and tested positive for bacillus leprae. One month later officials dumped him, alone, in an empty quarantine barracks on the island. He was the first.

His name was Will Vallance. Little is known of his life before Quail Island: he had come to New Zealand from Queensland in the mid 1890s, and had been working as a tailor in Christchurch since the turn of the century. When he was admitted to hospital he was thirty years old. He had probably contracted leprosy in Queensland, where the disease was more common than in New Zealand. It was not unusual that his illness took so long to reveal itself: symptoms of leprosy could take up to twenty years to appear.

Without any surviving diaries or letters, Vallance’s physical and mental condition during that first lonely year on Quail Island can only be guessed at. In July 1906 James Mason, who had recently returned to his post as chief health officer, visited the island and told the papers that the patient was ‘looking much better’; perhaps Vallance also had some quiet hope that he might soon be allowed to rejoin society.

At the time of Mason’s visit Vallance was living alone in one of the island’s old quarantine barracks. The emptiness of the building was testimony to the changes that had taken place in practices of medical segregation over the last thirty years. The rise of steam shipping had reduced the time available for diseases to spread, and also the need for quarantine facilities. By the early 1890s the effectiveness and fairness of the quarantine regulations themselves were being called into question: one doctor described them as ‘antiquated and most cruel to the patients’, observing that while a New Zealander with typhoid would be treated at a local hospital, an identical case arriving on a vessel would be taken to a quarantine station and dealt with by an ‘ignorant caretaker’. By the early twentieth century most cases of infectious disease were being treated at hospitals on the mainland. The complete isolation of Vallance, whose disease was chronic and only mildly contagious, is a measure of just how far reactions to leprosy differed from those to other diseases.

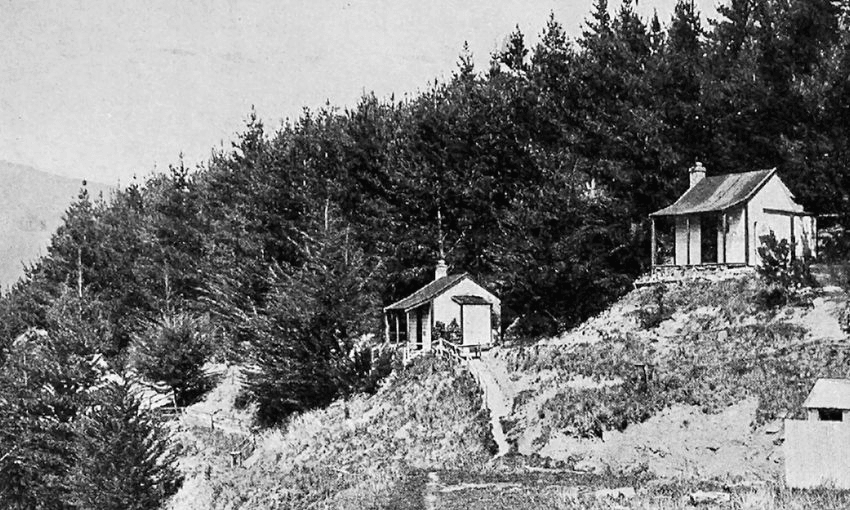

In April 1907, a year after he had been marooned on Quail Island, the Health Department built Vallance a hut of his own. The hut was small but solidly constructed, with a fireplace for the coming winter. It was perched in a pine plantation 200 yards around the inlet from the quarantine station. Vallance had apparently asked for a smaller dwelling after finding it impossible to get comfortable in the cavernous and empty barracks. The department was also starting to realise that Vallance’s isolation on Quail Island might not be a temporary affair after all: the construction of a hut could well have been a tentative step towards setting up a leprosy colony by stealth.

Vallance now had a new place to live, but his range was extremely limited. His conversations were held at a distance: he used a telephone to talk to friends, and spoke to the island’s caretaker and his family from what they thought was a safe distance. A white picket fence in front of his hut marked the point beyond which he was not allowed to pass. At meal times he would set out his plates on a small table at the end of the fence, and watch the caretaker fill them with food his wife had prepared at their house. His isolation was so complete that a reporter who visited him in 1907 was immediately put in mind of the Old Testament’s prescription for the ostracism of leprosy sufferers: ‘he is unclean; he shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his habitation be’. It was an accurate enough reflection of the department’s approach to his case.

Vallance’s isolation was compounded by the depredations of leprosy. He had lost the ability to manipulate objects with his fingers, so his meals had to be cut up for him in advance by the caretaker. When he first arrived on the island he was able to split his own firewood, but soon this too was impossible. It became a struggle to get up and go outside: by October 1907 he only had the energy to leave his hut twice a week. ‘The time is approaching’, the reporter saw, ‘when the poor fellow will become helpless and too weak to move out of his house, and the problem will be what to do with him then . . . he cannot be left to die unattended.’

Vallance did get some help in the early days of his isolation. Once a month (or more frequently if needed) he was visited by Charles Upham, the Lyttelton port health officer and general practitioner, who would change his dressings and make him as comfortable as possible. Upham, ‘the little doctor’, was a short and sprightly man, a familiar sight on the steep streets of Lyttelton as he made his way with pipe, walking stick and dog to the home of one of his patients. He had trained at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, and joined the British navy as a medical officer after his marriage fell apart. He arrived in Lyttelton in the late 1890s on the HMS Torch. ‘It was spring and the area reminded me of the French Riviera. I thought, this is where I want to stay.’

Upham taught the senior Bible class at Lyttelton’s Holy Trinity Anglican church, and would have been familiar with Old Testament attitudes towards the leprosy sufferer. He would also have been familiar with the New Testament’s examples of those, beginning with Jesus, who had set themselves to care for the sick and the outcast. He did not leave his religion at the door when he set out on a medical visit – he was known to pray for his patients, and believed that he himself had been cured of angina by a visiting faith healer at Holy Trinity. His acceptance of the job at Quail Island was a demonstration of his ‘practical Christianity’. When he took the job, though, he was only expecting to be looking after one patient, and that temporarily. As it happened, more were on their way.

The Dark Island: Leprosy in New Zealand and the Quail Island Colony, by Benjamin Kingsbury (Bridget Williams Books, $39.99) is available at Unity Books.