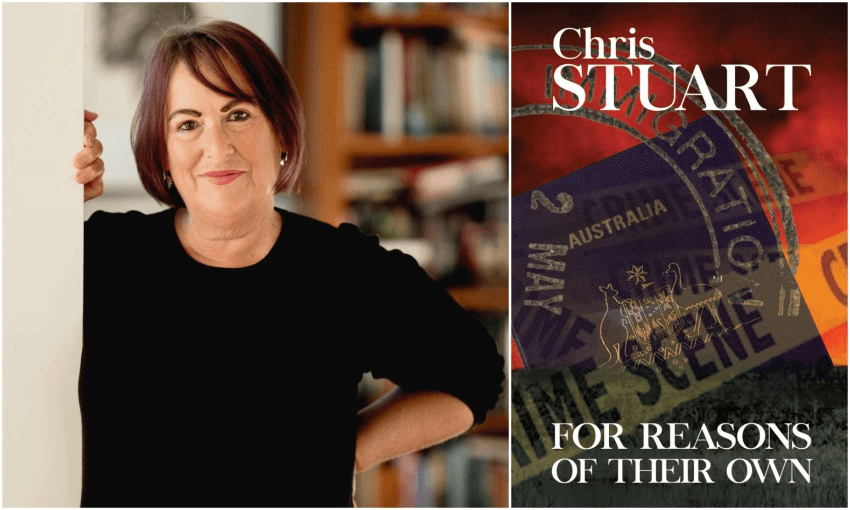

Christchurch writer Chris Stuart spent decades toggling between high-stakes overseas aid work and the strange safety of home. Out of that has emerged a crime novel: For Reasons of Their Own.

I used to always tell people that when you work in war zones and disasters, you are only ever a brick in the wall for making things better, or for making people aware of the plight of their fellow humans. Maybe my book will also be a brick.

It was originally conceived as an autobiography, with a focus on how a humanitarian worker, on return from each overseas assignment, adjusts to the return to safety and to their own “real world”. Like Jane, one of the characters in the novel, I was finding each time I walked into my home it was harder and harder to readjust.

I’d first been to the Middle East in 1991. It was the end of the first Gulf War; all the expats had left. I spent the next 20 years working in wars, disasters and areas of underdevelopment, mainly the Middle East. I have worked in Palestine, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Oman and Dubai, as well as Indonesia and the Pacific. I earned my wings in the outback of Australia working in Aboriginal health and this experience was excellent for preparing me for humanitarian work. I always argued that if we didn’t get in right in Australia, then we are not really in a position to tell anyone else how to do things better.

I have worked from encouraging young people to wash their hands to avoid disease outbreaks, to co-writing a country’s health strategy, to operationalising the first civilian-military cooperation response in the Solomon Islands. I was also a consultant and then a director for primary healthcare nursing in Dubai, as well as a team leader in Iraq, at the very end of that particular Gulf war.

I remember the huge culture shock of Saudi Arabia. I went from university in New Zealand to a fundamentalist country, from freedom to fear, from democracy to domination and repression, from enjoying a wine to almost abstinence. I didn’t realise it at the time, but there was an Afghani training camp on the outskirts of the town – I look back now and wonder if Osama Bin Laden passed me by.

This was my first experience of living under fear, feeling totally powerless, being told what to wear and how to act. Being demure is not in my nature and at times I thought I would explode. It was before the days of computers and we really had no communication with the outside world, so our families didn’t hear from us. We couldn’t leave, even if we wanted to, as our passports had been taken.

When I finally returned to New Zealand I still looked around to put on my abeya (the black cloak) before I went out the door. That habit took a long time to wear off.

I look back and laugh at this now: once I was walking past a car in Jerusalem. The car lights flashed and I heard a loud click. I dived to the ground, thinking this was a car bomb. It was just someone using an electronic car key.

When I am overseas, my radar is on and I am always security conscious. It is a shock to return to New Zealand – your safe place – to find yourself standing under a door jamb at 4.35 in the morning, with the very ground you are standing on shaking the hell out of you. I once had a knife thrust at me in Melbourne, when a drug deal on the 109 tram went wrong. It upset me badly because I was so unprepared for it. My guard was down. I thought I was in a safe place.

Over the years I became increasingly disconnected from friends and family. Coming home was like walking into a picture theatre where everyone I knew was watching some really exciting movie. I’d take my seat and try to catch up on what was happening. Everyone else knew the storyline but I’d always need to catch up. I accepted this because I was content to at least be sitting in the same row and feeling included. Afterwards, tickets would be discarded, and contented and unaffected lives moved on.

The people I love must have felt this way about my life, too. No one really understood what I was doing and sometimes it was just too hard to explain. At one point in time, when any stranger asked me what I did, I would tell them either that I was an alpaca breeder or that I painted the veins on prosthetic limbs. I describe Jane like myself – as having seen a lot, and coped.

I started to write in 2005, and after a year and a half I decided no one would be interested in me or my story and with no support, I deemed myself a useless writer and put the book in the bottom drawer. I went overseas again, to the Solomon Islands for a year, followed by post-tsunami work in Indonesia and two more years in the Middle East.

The theme of returning home, and of what it means to be safe, continued to haunt me.

Take two came eight years later and found me better armed. I’d done a few courses in writing, a few weekend workshops, a few book clubs, online learning, writing groups, book fairs, writers festivals, meeting authors, reading and reading and finally winning a short story competition. However, I knew that I could not write, could not give my best effort, unless I was 100% committed. My overseas work always consumed every waking hour, and usually intruded into my dreams: I would dream about work and what we needed to do, what we knew or didn’t know, what were the risks we needed to consider, who was affected, who needed us the most.

Often we were under real pressure to make a difference fast. I recall being in Iraq and access to drinking water was scarce – the holding tanks had been bombed – so people were digging up pipes in the street. I wanted to keep the children under five healthy, so we targeted water for them, but then realised there was so little water that we had to target the babies. Even though we were close to the river, when the river water was tested, it was like drinking from your toilet after you forgot to flush.

Especially during a war, or right after, the situation would be complex and volatile. I was always conscious of security – especially as a team leader, when you need to keep your team safe.

I could never take a book away on missions, so I used to take a magazine of cryptic crosswords and would do one over two nights. It helped me switch off.

Four years ago I decided to return to New Zealand and worked for Red Cross. Two years ago I stopped doing that full time, and dedicated myself to the writing of this book.

I still felt that a story about me wouldn’t be exciting enough for a reader. So I wrote a crime novel loosely based around the humanitarian world. Writing fiction gave me wider scope, more opportunity to be original and to include more interesting characters, and allowed me to tell a story without sounding didactic. In essence, For Reasons of their Own is an amalgamation of many years of humanitarian work. It contains the observations and the frustrations of seeing very little improvement in the lives of those people in the world who are most vulnerable and most invisible.

There are several themes running through the novel. It should challenge our notion of what it means to be safe. It asks whether we can ever really escape the past, and it highlights the courage of women. It is also a contemporary novel, touching on corruption within United Nations agencies, border fluidity in times of war, power and powerlessness, and how governments use fear to manipulate people and direct policy.

The contrast between the antagonist and protagonist adds a further dimension to the storyline, although this perhaps isn’t obvious until the end. The two women are from different continents, both raising children and making different life choices which I am hoping the reader will think about long after the last page is closed.

I am not an imaginative writer. Everything I write is based on what I know, what I have felt, or personally experienced. The main character DI Robbie Gray is a little like me. She is a former nurse, comes from a dysfunctional alcoholic family and she is raising a daughter alone. Which of those aspects are like me? Here’s what I’ll say: she is flawed, but resolute. She feels a deep empathy for the powerless, but has enormous anger for those who abuse power. She wants to make the world a better place. Like me, Robbie realises that the damage done to her family through alcoholism is something she can’t fix, and this is a dilemma for her when she wants to help fix other lives. That’s why I love that she is named Gray. Life for her is never black and white and it is full of contradictions and dilemmas.

Other characters in the book, related to the humanitarian world, are based on people I have met (except for the murderer. I know no killers). Mac, my lovely Aboriginal policeman, is based on my experiences working in the outback communities of Western Australia and Cape York. To the people in these places, I owe a huge debt of gratitude.

I am afraid all the male police characters are the product of my fertile imagination, although my father and brothers were policemen. However, I do know the city of Melbourne and its graffitied laneways very well; I plan my second novel around this area.

Whenever I was living in Melbourne, I stayed in a rural town similar to Palmerston North and frequently took the train into the city. I would look out the train window at a small, isolated swamp, with its black water, lace-edged reeds, and eerie atmosphere, and think about how easy it would be to hide a body there.

For Reasons of Their Own, by Chris Stuart (Original Sin Press, $35) can be ordered from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.