An excerpt taken from the introduction to Dad Goes to the Movies (1941), a World War II diary edited and published by Auckland writer Jaq Tweedie, the daughter of serviceman Les Tweedie.

Everything has a beginning and an end, and when I was young I was mostly interested in how things started. I knew my father had fought in World War II and one day I asked him where he was when the war broke out.

I was at the pictures, he said. I was at the Capitol in Dominion Rd in fact, with my girlfriend Peg.

John’s Mum? I said. John is one of my two half-brothers. Yes, said Dad, but we weren’t married or even engaged yet. We were at the pictures, and it was the beginning of the show, and we all stood up to sing the national anthem. You always did that before the movie in those days. Then suddenly the manager came up the front and stood in front of the screen and said:

Ladies and Gentlemen, we are now at war.

I think there was a respectful silence. It wasn’t a shock or anything – we had all been waiting to hear, and this was how the people in the Capitol Cinema heard. Then we all sang “God Save The King” and sat down and watched the film.

What was the film? I said.

Oh, I don’t know, he said. Probably something with Fred and Ginger.

What was it like being a soldier in the war, Dad? I asked him. Oh, you know, the Army, he said. “Hurry up and wait.”

My Dad’s diary from 1941, when he was in the Army during World War II, is pretty boring. I guess most soldiers’ diaries are boring. Nothing much happens in them except busywork and drinking and shenanigans with comrades and the local girls – not all of which are documented – until the last day of the diary, sometimes a blank page followed by other blank pages, where suddenly the war happened to the soldier and he didn’t live to write about it.

The best soldiers’ diaries are boring, written for themselves, with every page filled (and no blank pages at the end) with weather reports and correspondence details and the dull everyday ephemera of a soldier’s life and perhaps, as in Dad’s case, an index of names cross-referenced with the dates they appear. I wonder how often, after the war, he raked through that tiny oilskin-bound book, and deciphered his own impossible handwriting to remember what they did together, what had happened.

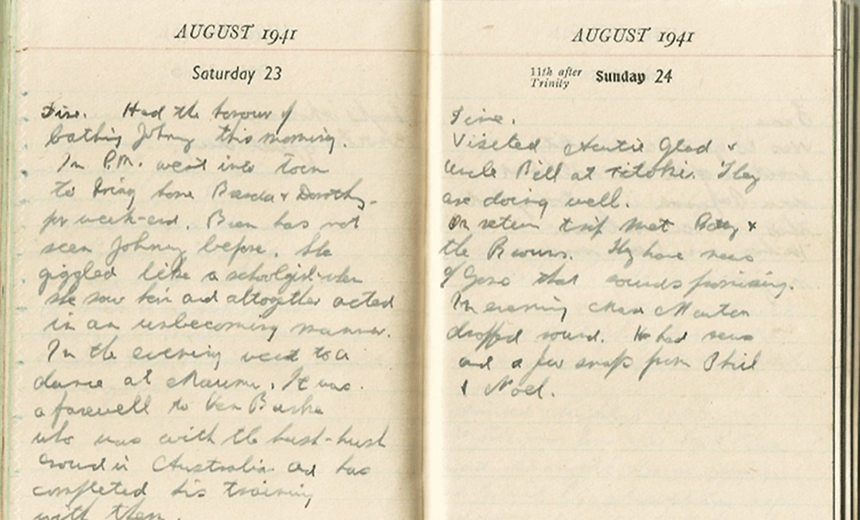

My brother-in law Brian found the diary after Dad died. In her grief, Mum dealt with household bills by shoving them into the drawers of Dad’s desk and ignoring them, and after a few months Brian discovered this and took the situation in hand. In the back corner of one of the drawers, was a standard soldier’s issue a 3”x 5” Collins NEW ZEALAND HANDY DIARY FOR 1941 – a page-a-day, personal account of one of the most interesting years of the 20th century. Unfortunately, my father had written it in his microscopic yet loose and ragged cursive handwriting, and it was illegible.

Twelve years later, after my brothers and sisters had all tried to read it, the diary was turned over to me. I’d had no idea it existed, so I was ecstatic. I was warned that it was unreadable, and if I managed to parse anything from the handwriting it would be dull anyway, but I determined to decipher the whole thing. It took months to transcribe it, and for a while I got blinding migraines from reading it and had to lie down after, but I did it.

Perhaps it’s just me, but this diary isn’t boring. Being a soldier in a war is boring, for sure. Life is full of counting things and reorganising things, petty quibbles about supplies and other soldiers, and being marched up to the top of the hill and marching down again. It’s as boring as any job, except that these men were taken from their useful jobs at home and compelled to do it. Thousands, millions of men all over the world, sent on a six-years-long Boy Scout camp with live ammunition.

I know I’m biased, but Dad was a good writer, even in the abbreviated form he had to use in this tiny book. Not just what he does, but what he thinks and feels about it are here. And he didn’t just write the diary – over a hundred letters are logged here to his wife Peg, his sister Ailsa, his mother Kate and others, as well as sketches and jokes for soldier’s theatricals and newspapers.

Long before I read this diary, Dad taught me the meaning of “Lest We Forget”. It means – don’t forget the Lost Generation after the Great War of 1914-1918, when so many men were killed and maimed that all over the Western world the demographic of “Men aged 18-30” simply disappeared.

Don’t forget that the next 10 years were a spree of consumption as people TRIED to forget, which ended in ruination for everyone. Don’t forget the Depression that followed, and the money and men invested in war that were never returned. Don’t forget that a bigger, longer, more horrible war happened only 20 years later: a war with new rules that included bombing citizens and destroying entire cities.

My father had little respect for the RSA. He told me once he thought they were a bunch of fools who just liked to drink and brag. He went to the Dawn Parade on Anzac Day every year though, in civvies, not in uniform. I remember going with him. I remember him remembering. I won’t forget.

Dad Goes To the Movies (Dunbar Noon Publishing, $22.95) is available at Unity Books.