True crime aficionado Jean Sergent reviews The Five by Hallie Rubenhold.

In the annals of Ripperology, there are classics and there are clangers. The latest slew of “Jack the Ripper finally uncovered!” headlines recycle the same faulty DNA studies, but there has never been a definitive answer to the mystery of identity of the Whitechapel murderer. Patricia Cornwell sunk millions into her pursuit of artist Walter Sickert, and she made a compelling case in her bestseller Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed, but there’s just not enough solid forensic proof. Aaron Kosminski is the current favourite, but that might be more a combination of latent anti-semitism and the vilification of mental illness than inarguable evidence. The mystery endures.

What shouldn’t be a mystery though are the lives of the five canonical victims of Jack the Ripper. That’s the crux of Hallie Rubenhold’s new collective biography The Five: ask not who was he, but who were they. Giving so little page time to the killer as to almost ignore him altogether is revolutionary in the annals of crime literature.

And it turns on its head the central trope – the central pull, perhaps – of true crime, right now one of the most popular genres of podcasting and television. Engagement with such content can be seen as a morally precarious pastime. What does it say about me, a woman in my thirties, that I know so much about serial killers? People who don’t “get” true crime often look askance at those of us who like nothing more than to find another murderino at a party. Although I don’t condone cheating at pub quizzes, if you text me to find out which murderer was once a contestant on The Dating Game I will respond “Rodney Alcala” and I hope you’ll win the quiz.

However, it has been argued that many people with a thirst for true crime are stockpiling information out of a sense of morbid anxiety. If we can recognise circumstances and personality traits that are associated with the darkest edges of humanity, maybe we can somehow psychically protect ourselves. Be prepared.

While it honours five women as individuals, the book is also a searing, sweeping social and feminist history of the Victorian era. Dickensian in its proportions, it places that most Victorian of authors in the neighbourhoods of the story, giving the reader further imaginative access into 19th century London slum life. The Five is an important contribution to women’s social history, as well as the social history of the under classes.

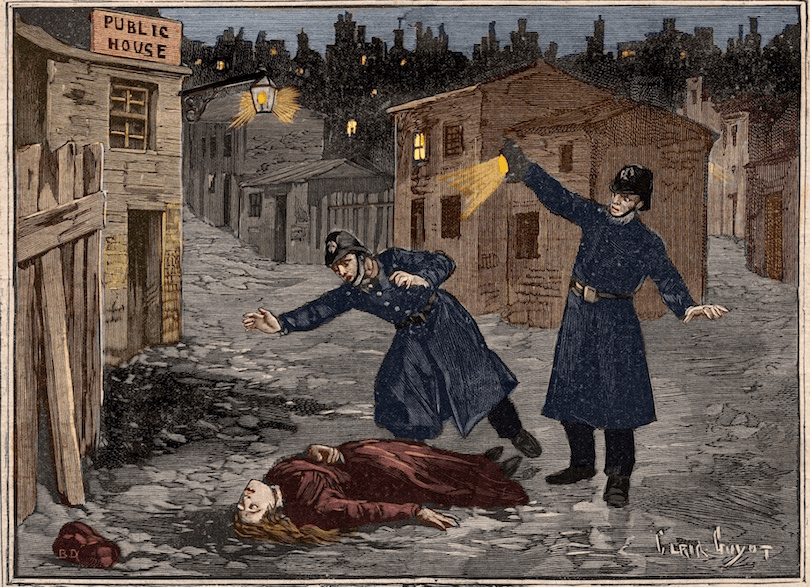

Early on it is established, contrary to popular misconceptions about the victims, that it’s likely only two of the five women were sex workers. Thus the prostitute killer is reframed as what he was: a killer of women. Barely 20 pages in, the author turns the tables in the most devastating way: it’s not that these women were lured into dark alleyways with the promise of money – it’s more likely they were targeted because they were asleep. The dark alleyway was where they had chosen to hide from the world in order to catch a kip on a frigid London night.

I point out that they were women, not “prostitutes”, because the almost routine degradation of sex workers in true crime reporting and policing needs to be redressed. The term “ripper” in criminology is a colloquialism derived from the Whitechapel murders and applied by the British press to any serial killer of sex workers – the Yorkshire Ripper, the Ipswich Ripper. This is one of the cruel and dehumanising legacies of the one they call Jack: his victims are made to stand as emblems of morality. It’s sexist, it’s simplistic, and it’s totally inaccurate.

There is breathtaking anguish within these pages, made heavier by knowing how the story ends for each of these women. They are more than their names and mutilations. While aspects of their lives and experiences intersected, each of these five women was an individual with her own story. All but one were mothers; all but one were literate; all bar none deserve to be known as more than another dead woman.

Polly Nichols’ life story has moments of great hope. When her family is given an apartment in Peabody’s brand new tenements you think maybe, just maybe, this will be enough to save her. The gossip and intersecting lives of the housing estate residents seem a bubbling utopia after the mouldering grime of the slums a few streets away. Infuriatingly, a husband with a wandering eye is all it takes for a major reversal of fortunes for a working class Victorian woman.

Annie Chapman’s young life is a fascinating combination of military schooling, epidemiology, and tantalising closeness to the great and famous. (Her neighbour was Isambard Kingdom Brunel!) Annie and Polly had an advanced education in common. Decades before universal schooling for the 5-12 year old set was decreed in law, both Chapman and Nichols were educated well into their teens. But what use is an education in a world that won’t allow you to survive unless you’re under the protection of a man? Both Nichols and Chapman endured marriage breakdowns that left them totally vulnerable to the degradation and humiliation of workhouses. For Chapman, addiction to alcohol as well as marital disharmony was her downfall, something society still punishes people for today.

Elizabeth Stride had been a sex worker in her native Sweden, or at least that’s what the judiciary labeled her as: Public Woman number 97. Emigration to England provided this clever woman with multiple opportunities to reinvent herself, and she wasn’t averse to using morally dubious ruses to finding pity and charity. Fair enough, I think. Although it’s pretty dodgy to claim to be a survivor of a shipping disaster, if you’re a woman alone in Victorian London I think you’re entitled to survive any way you find. ‘Long Liz’ seems like she was a very rude and strong-willed woman, and I like the sound of her. She had already paid for her lodgings the night that she died, and presumably was back out on the streets because she fancied a drink and a laugh. When she died she was holding some throat lozenges.

Kate Eddowes’ life story is full of intriguing Victorian job titles – chapman, tinman, ballad sellers, and costermongers. All terribly romantic-sounding, but the reality was endless workdays, drudgery, and pitiful wages. Kate was a spirited and well-educated young woman. I took personal note of the fact that she was an Aries, and it delighted me no end that she was willing to throw in a life of polishing trays for 12 hours a day in order to follow her Irish boyfriend on long walks selling books and toys in pubs. But even with Kate the cycle plays out: a working class woman, no matter her education, is bound for marriage or the dull horror of vagrancy. In the years before her death, Kate’s alcoholism had driven away most of her family. The night she died she’d spent her doss money on booze. Like Polly Nichols before her, she was just looking for somewhere to curl up for a kip.

Mary Jane Kelly is arguably the most well known of the Whitechapel murder victims, possibly through her bizarre portrayal by Heather Graham in From Hell, but more likely because she was the last victim and the youngest. The strange irony of her fame is that so little is known about her, especially in comparison to what Rubenhold compiled on the four other victims. Her part of the book is half the length of the other four biographies, and not just because she lived half as long. Mary Jane’s story is closer to the sex worker story we expect from the Ripper victims. Her high class West End brothel career took a sharp turn toward European sex trafficking, before she ended up in the unfamiliar squalor of the East End without any of the fineries she was used to.

Rubenhold has painstakingly researched the sad, short, and unremarkable lives of these five women. The notoriety of their deaths is largely unimportant in their biographies – after all, the moments of the murders are mere seconds of their lives as a whole. This is true of the deaths of countless murdered women. Social backlash against cultural products like the upcoming Ted Bundy biopic are often predicated on arguments against perceived hero worship of scumbags, alongside virtue signalling to remember the names of the victims. Ted Bundy killed 30 women, 10 of whom were never identified – but we know his name. Similarly, so much of “Ripperology” is concerned with the identification of Jack himself. Large volumes have been written in search of his identity, and no one has managed it. Rubenhold’s book says who cares to that useless endeavour. Instead it’s an invitation to know the victims, as well as we can, outside of their brief but awful final encounters with an unnamed asshole who killed vulnerable women while they tried to get some sleep.

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold (Penguin Random House, $40) is available at Unity Books.