Danyl McLauchlan reviews the new election memoir by baffled sore loser Hillary Clinton.

What did Hillary Clinton do after losing the election to Donald Trump? Pretty much what you’d expect: she cried; she prayed; she read books and poems (inevitably by Maya Angelou); she watched movies with her husband; did yoga with her personal instructor; oversaw the interior decoration of the large house she bought next door to her current home in upstate New York; bonded with her friends; played with her grandkids; went for long walks in the woods of her estate.

All that self-care sounds nice but I’m not sure all that poetry and yoga and interior decoration brought Clinton close to understanding the rage many Americans have for their political class; a class for which Clinton was and is a potent symbol, and a rage that her adversary Donald Trump stoked and fed with malevolent skill. Even though her book is supposed to be an explanation of What Happened, Clinton still clearly finds the result incomprehensible. How? she marvels. How could they choose him over me?

So what happened?

According to Clinton it was a combination of things. Sexism. The media. Bernie. Putin. The FBI. Oh, she made mistakes, sure. Those paid speeches to the banks? That was wrong. Lots of other politicians do it; male politicians, if you get her drift, and somehow it’s no big deal for them but when she, a woman does it and everyone loses their mind, so what’s up with that, huh? is maybe a question we could all be asking ourselves. But yeah, OK, taking quarter of a million dollars from Goldman Sachs only two months after she left her role at the State Department in preparation for a presidential campaign and refusing to disclose what she talked to them about was bad optics, in hindsight. She admits that. And the private email thing? That was a bad call. That’s on her, and she’s apologised for that so many times now, okay. But really? Emails? They could have had the First. Female. President. Of. America. And they chose that disgusting, ignorant orange monster, who boasts about grabbing woman by the pussy, over her, all because of some fucking emails? Seriously?

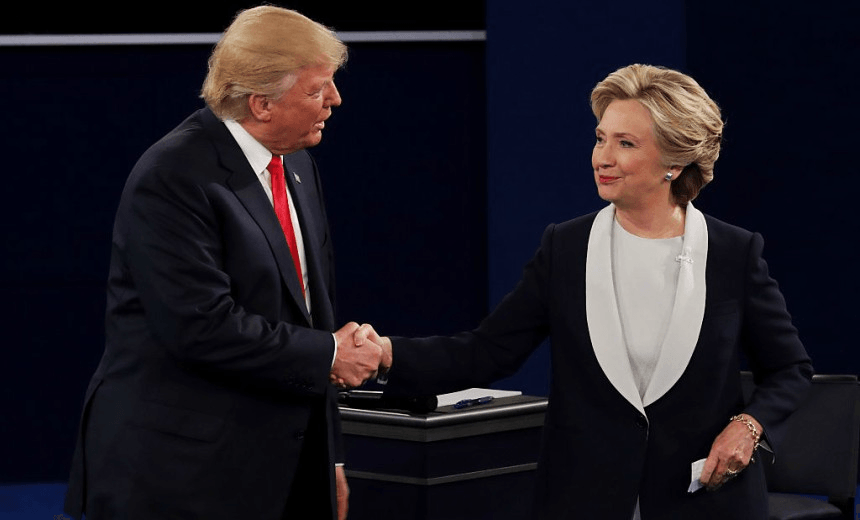

I didn’t pay much attention to Clinton during the 2016 US presidential campaign. I was too horrified and transfixed by Trump. I didn’t want Clinton to win so much as assume her victory was inevitable because the alternative was unthinkable. Then I watched one of the debates on live-stream and was shocked by how glib and insincere Clinton seemed: so scripted and focus-grouped; she personified everything people dislike and distrust about modern politicians. Lucky for her she’s running against Trump, I thought, otherwise she’d lose this thing.

It baffles and enrages Clinton that people have that gut reaction towards her: that we don’t like her, don’t trust her, don’t find her authentic. “I’m me!” she writes. “This is who I am!” and you can sense her frustration, and hear it echo back through the hundreds of meetings she must have had with pollsters and media trainers and market researchers and focus group convenors, all of whom must have told her variations of the same thing. “They don’t like you, so you need to be more likable, but when you do that they find you inauthentic, so you need to be yourself.”

It’s a form of sexism, Clinton argues. A lot of What Happened isn’t actually about What Happened. It’s mostly a political memoir with an emphasis on Clinton’s brand of centrist second-wave feminism, with long segments on her childhood, and sisterhood and motherhood and grandmotherhood, and being a woman in politics, mixed in with descriptions of the various worthy policies Clinton campaigned on, many of which were for women, and which she cannot believe people didn’t vote for because they would have done her country a lot of good, and as the First Woman President of America she would have done a great job implementing them, by-the-way. There’s a section on what she’d have done in her first 100 days as president, and it would have been a lot more than that drooling piece of human trash sitting in the White House right now getting nothing done. A hell of a lot more.

There’s material about Clinton’s life as a young feminist and anti-war activist who decided to change things from within the system; her life as First Lady; Senator for New York; Secretary of State. All of this is broken up with dozens of Oprah-style quotes of the believe-in-yourself-and-reach-for-the-stars-and-follow-your-dreams school. Other readers might engage with this material more than I did: if you think girls can do anything, but that girls must also understand that doing things is tough, and requires a lot of compromise and hard work and disappointment; like, sometimes, a lot of disappointment, so much disappointment you really can’t imagine, at times, then you’ll love What Happened. I found it less interesting than any memoir of the vicious and deranged 2016 campaign has any right to be.

Clinton is more engaging when she talks about the challenges of being a woman in politics. Women rise to leadership positions in parliamentary political systems, she argues, because those are systems where the leader is decided by the caucus, where more feminine leadership styles that reward relationship building and emotional labour can flourish. Presidential contests are more about traditionally masculine approaches to politics: whipping up the crowds; dominating in the debates. “Trump is hateful,” Clinton admits, “but it’s hard to look away from him.”

“Hateful but hard to look away from” is also a pretty good way to describe Sarah Palin, though, who was a dab hand at whipping up a crowd. And Clinton won her debates against Trump hands-down according to every focus group of undecided voters the media measured. Society is sexist, but society is also racist and Obama won two elections against tough, credible candidates while Clinton lost to the worst candidate anyone had ever seen. One of the things that fascinates and baffles me about the final outcome of that race is how irrelevant gender was to the final vote. Clinton won fewer women voters than Obama. Trump won a majority of white women voters. How is that even possible? I don’t know. Neither does Clinton.

Here’s another mystery. Clinton’s approach to politics is the weirdest mixture of idealism and hard-nosed cynicism, and her instincts seem to lead her towards cynicism when she needs to be idealistic, and idealistic when she needs to be cynical. Exhibit A: Clinton decided that the 2016 campaign was going to be about policy and experience. She prepared for a policy based campaign, and poured huge amounts of time and money and energy into having the most comprehensive, costed, detailed policy agenda any presidential candidate had ever had. The campaign would be about the tough, complex, nuanced issues, Clinton judged. Especially foreign policy issues.

It’s hard to think of anything that’s happened in Clinton’s lifetime in politics that made her think this kind of campaign was remotely likely, or that the national media or her rivals in the Democratic Party or mortal enemies in the Republican Party would indulge this fantasy of hers, yet she’s outraged that it didn’t play out like this; outraged that the media and her opponents behaved the way they always have, and always will.

At the same time she’s also outraged that Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump campaigned on visions and gut emotions and promises, instead of telling the voters the truth about how difficult and compromising politics is, and how real, meaningful change is basically impossible to deliver, and how all their grand visions and idealism were worthless, because real politics isn’t like that at all. And what’s so great about change, anyway? “Change might be the most powerful word in American politics,” she writes, but: “In 2016 change meant handing a lit match to a pyromaniac.” Why would people want change that badly?

What happened? Why did Clinton lose? Why was she an idealist when she needed to be a realist and a realist when she needed idealism? I don’t know for sure, but there are clues in this book. Clinton makes the final decision to run for President because, she tells us, she wants to make a real difference to the lives of real, hard-working Americans, but it’s a conclusion she reaches while vacationing at her good friend Oscar de la Renta’s estate in the Dominican Republic. To help innovate on how to connect with those real Americans, who have been left behind by the economy when it was hollowed out by transnational corporations, she brings Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google onto her campaign team. Clinton lives and breathes a world of elite wealth and power that most voters are completely alienated from, and the inhabitants of that world profit from an economy and culture the rest of the country distrusts and resents, for good reason. But it’s a system that has treated Hillary and everybody she knows fabulously well. Why should she want to change it?

At one point in the campaign – one of the debates, I think – Trump asked a question that came back to me mid-way through this book. Hillary and Bill Clinton were, famously, broke when they left the White House in 2001, Trump pointed out, cleaned out by all the legal fees. But by the time she faced Trump on the debate stage the Clintons were worth an estimated $240 million. “Where’d all that money come from?” Trump demanded. It’s a pretty good question. Bill was a retired politician running a non-profit charity. Hillary was Senator for New York and then Secretary of State. How’d they come by a quarter of a billion dollars?

A few days before Clinton announced her candidacy, the New York Times ran a front-page story on the Clintons’ finances and the murky links between the Clinton Foundation, Bill Clinton’s work as a speaker and lobbyist for various global corporations and billionaires, and Hillary Clinton’s high-ranking role in the Obama administration. Bill’s speaking fees tripled as soon as Hillary went to work for Obama, and many of the largest payments came from international companies who relied on contracts with or had business before the State Department.

Moreover, when Hillary became Secretary of State she promised that she’d disclose all foreign donations to the Clinton Initiative to prevent any conflicts of interest. The article revealed that this did not happen and that huge undisclosed cash donations from numerous foreign entities, including foreign governments, many of which were guilty of egregious human rights violations, had been channeled through Clinton Foundation subsidiaries, and that many of these created conflicts of interest for Clinton.

This was all a right-wing smear, Clinton protested. And, in a way, she was right. All of this research had been carried out by a partisan right-wing group created by Steve Bannon, a white nationalist activist who would go on to become Donald Trump’s campaign director. Bannon hired teams of researchers, forensic accountants and computer scientists to find out everything they could about the activities of the Clinton Foundation. But the stories they uncovered were run by the New York Times and the Washington Post because their journalists and editors deemed them credible and accurate. Since they were sourced by her enemies, however, they were timed to inflict maximum damage on Clinton’s campaign. And they were devastating. “You look at what they’ve done in the Colombian rainforests,” Bannon told reporters, “Look at the arms merchants, the warlords, the human trafficking – if you take anything that the left professes to be a cornerstone value, the Clinton’s have basically played them for fools.”

It got worse. The revelations tied into another Clinton scandal: the emails. While she was Secretary of State, Clinton routed all of her emails through her family’s private email server. It was a violation of national security but nobody except the Republican Party seemed to care – until the Clinton Foundation stories emerged, and it started to look like Clinton had sought to circumvent government oversight, and that she’d deleted tens of thousands of emails that might have been material evidence of corruption. By the time Hillary Clinton won the Democratic nomination – the first ever female candidate, she reminds us, many times – she was the least trusted, most unpopular candidate for president in history.

Except for Donald Trump.

So what happened? In the final weeks of the campaign things looked pretty good for Clinton. She was leading in every poll. Trump’s campaign had been devastated by the Access Hollywood tape, and his despondent strategists had identified one last remote path to victory: a group of voters they called “the double-haters”: millions of former Obama voters in key states across the industrial Midwest who disliked both Clinton and Trump. The only way Trump could possibly win, they concluded, was if the Clinton-leaning double-haters stayed home but the Trump-leaning double-haters all decided for Trump. And what were the chances of that?

Enter Clinton’s close aide, Huma Abedin and her husband Anthony Weiner, a former New York congressman who resigned from office in disgrace after being repeatedly caught sending pictures of his dick to numerous women. At some point, months earlier Abedin had downloaded some of Clinton’s redirected emails onto her laptop. During the campaign it emerged that Weiner had sent dick pics to, among many others, a 15-year-old girl. The police investigated, seized the laptop, found Clinton’s emails and took them to the FBI, who, 10 days before election, reopened the email investigation and notified the public (because, FBI director James Comey later explained, if he hadn’t made it public it would have leaked).

To the delight of Trump’s strategists and the horror of Clinton, and the rest of the world – and even the dismay of the rest of the Republican Party, who despised Trump and were already gloating in anticipation at his loss – the double-haters in the industrial mid-west responded to the news of the investigation by breaking for Trump in exactly the way needed to deliver a Trump win.

Clinton still won the popular vote. She really wants everyone to remember that, even though it’s meaningless: if the popular vote won the contest the Republicans would just maximise turnout in Texas. Trump won the electoral college, and he gets to be President, albeit an ineffectual and increasingly aimless President. We’re 10 months into that, another 38 to go. It’s been fairly awful, though it could be much, much worse. I think the real threat is still ahead of us, in the future: someone who channels the same rage Trump tapped, that loathing and contempt for the elite financial and political class that Clinton represents, but then uses their power instead of squandering it golfing and tweeting.

Whose fault was it? What caused it? How do you assign causality to something so complex? Steve Bannon had an answer. He’d spent the last week of the campaign telling all the journalists he knew that their polls were wrong; that none of them understood politics, that Trump was going to win. When he turned out to be right they sought him out and asked him what happened.

“Hillary Clinton,” he replied, “was the perfect foil for Donald Trump.”

What Happened by Hillary Rodham Clinton (Simon and Schuster, $50) is available at Unity Books.