A new book by Tony McCaffrey deals with stage performances by people who have intellectual disabilities.

John Lambie was an actor with Down Syndrome. He had had been part of the initial intake of children in 1965 into Hohepa Canterbury, a residential community in Christchurch for people with intellectual disabilities, run on the principles of Rudolf Steiner. In 2015, John had celebrated 50 years in that community, as well as 50 years away from his family of origin. A few weeks after the celebration he was transferred to a dementia centre in Ashburton, some hours’ distance from Hohepa Canterbury. He died in 2016.

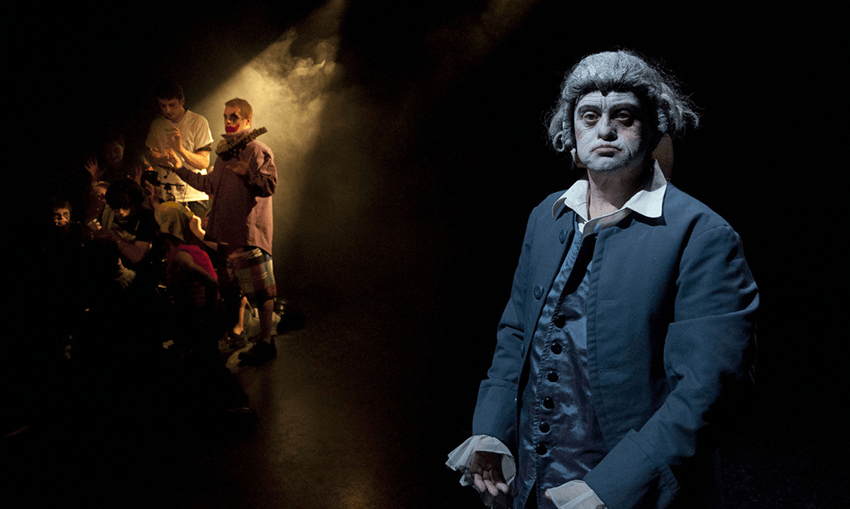

John was also a founder member of Different Light Theatre in Christchurch, which created works involving actors with a range of intellectual disabilities. Different Light produced a performance, Three Ecologies of Different Light, to commemorate his life. The challenge we faced was to celebrate somebody we all knew and had worked with, and who had lived a life in segregation.

A number of performance strategies were suggested: showing video and images of John, re-enacting a movement sequence that John had part-choreographed and performed on a tour of Australia, baldly reciting the facts and figures of John’s life. None of these seemed adequate and all of them were all we had to be adequate to John’s memory.

In addition, there were a number of sequences involving the whole group counting from one to 50, the number of years John had been institutionalised. The group counted from 1 to 50 getting louder and louder. They counted backwards in whispers, eyes shut, clinging on to each other, and trying to move. The sound of their voices was slowed down as they moved in slow motion.

This very literal, communal counting of the years forwards and backwards had its own performative logic. But when placed in front of an audience the repetition verged on tedium. As well, the tediousness of the task meant that mistakes and uncertainties in counting were made. These were not the result of the intellectual disability of the performers; they were comments on the repetitive tasks of education and theatre-making. They didn’t set out to represent John’s 50 years of institutionalisation: instead, they became disciplinary operations of theatre in their own right, in response to which the actors found their own ways of resisting – speeding up or slowing down to disrupt the rhythms of the communal voices or movements, deliberately going out of sequence.

One assumption behind theatre involving actors with intellectual disabilities is that it should give voice to, tell the stories of, and enable the performers. In my 15 years of working with Different Light these have certainly been motivating factors. But all of us working together at the theatre have come to realise and experience how complex this process is.

In an earlier production, Still Lives (2011-12), three performers – Glen Burrows, Ben Morris and Isaac Tait – collaborated in devising a piece ostensibly about the Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 but more about their own sense of placelessness in the city both before and after the quakes. The piece made a direct comparison between the tectonic shifts of the earth and the bodily movements of Glen Burrows, an actor with cerebral palsy, a motorized wheelchair user, prone to seizures that he and his carers termed “sparking”.

The process of giving voice to Glen was caught up in the complex process of his accessing his own voice even on a pragmatic level. His own speaking voice appears impaired in that it does not seem to consistently navigate the flow of vowels and consonantal stops, although there are phrases that he articulates very clearly. His access to his own voice is complicated by the fact that speech therapy does not seem to help and he has had a range of devices to supplement or replace his spoken voice. These have included a Dynavox speech synthesis device which was always freezing and needed to be sent to Sydney to repair. He’s also experimented with various laminated booklets of letters and set phrases that he can use to indicate by pointing, and latterly an iPad. Glen is very fond of the iPad. But his fluctuating access to motor control with his hands means that it’s difficult for him to achieve anything like everyday, basic levels of fluency or immediacy of communication.

As for Ben Morris, giving voice to him in Still Lives was about finding some framework that allowed him to articulate his anxiety. Negative voices seemed to accompany his movements through a city which was at the time increasingly proscribing where the city’s inhabitants could go; red zone areas were restricted to authority figures in hi-vis clothing. How to represent that? One strategy was to have Ben recorded on video talking to Ben live on stage.

Giving voice to Isaac Tait was a question of trying to honour his much quieter voice – the gaps between words and phrases that echoed the gaps between buildings in the ghost town environment of Christchurch’s post-earthquake red zone. It also echoed the disconnect between Isaac’s persona of himself of a young prince, and the bullying and abuse he was subjected to in his part-time job at McDonalds. Although his voice was the quietest of the three it was his carefulness in performing a hongi on the other two actors at the end of the piece which united the different rhythms of each one’s voices and breaths.

In the devising of Still Lives, different voices of authority were explored and all used in the performance mix. Some of these voices were run through speech synthesis software as a nod to Glen’s Dynavox and iPad voices. They included goo-goo, ga-ga baby language, to describe being interrupted in the act of masturbation, conflating the infantilisation of the young men with their difficulties with expressing themselves sexually.

I must of course acknowledge that, significantly, Glen Burrows, Ben Morris and Isaac Tait are not collaborating with me on giving this account, beyond giving me their approval to write about our work. But the collaboration we experienced in the devising and performance of Still Lives has been resumed in my book about the 15 years of working together – written, assembled, and devised by the whole company.

Incapacity and Theatricality: Politics and aesthetics in theatre involving actors with intellectual disabilities by Tony McCaffrey is available online through Unity Books.