Auckland writer Kirsten Warner on the continuing horror of the Holocaust for second generation survivors.

A Facebook friend recently made contact to say he’d heard me talking on National Radio about my newly published novel The Sound of Breaking Glass. His wife was, like me, the child of a survivor of the Holocaust. He said he’d been a bit Anglo-Saxon over the years, shying away from the downstream and full-on emotion of this traumatic history and a father-in-law who would weep at the opening of a birthday card.

Weep, I thought? Some survivors can weep.

He’d come to empathise with his partner’s inheritance, and said he’d buy my book for her. He sent me a link to a New York Times article about the Japanese diplomat in Stockholm who issued 6000 visas for Jews desperate to get out of Europe in World War II. The diplomat had lost his job, but flung signed visa forms out the window of the train as he left the city, and lived the rest of his life working a menial job but without regret. It was through the bravery of this person that my friend’s father-in-law was saved.

So this history continues to ripple across our lives.

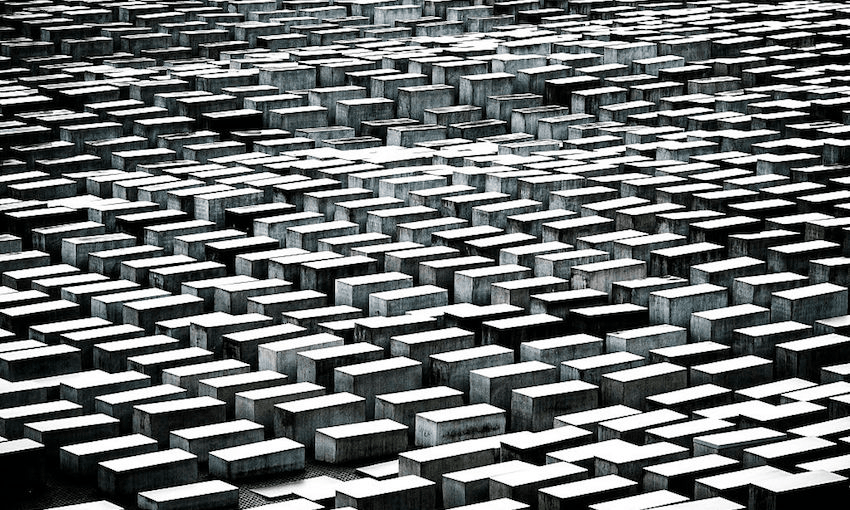

Earlier this month was the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht. On November 9, 1938 the Nazis killed at least 100 people, burned down hundreds of synagogues, vandalised and looted thousands of Jewish businesses and 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. In 1938, too, the first of the Kindertransport left, taking a total of 10,000 Jewish children to safety in Britain.

My father was a teenager living in Berlin and witnessed Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. His brother, aged 14, was on the last Kindertransport leaving Berlin. Both of them ended up living in New Zealand.

Dad was grateful and happy to become a New Zealander and serve in the RNZAF. He considered himself a refugee, yet he had only just survived. The problem was not so much getting out of Germany, it was which country would take you. The struggle was to get in. Hence the Japanese diplomat’s heroism.

I didn’t want to tell the survivor story in my novel – although I have on the way told a fictional story of another survivor who is not my father. I wanted to write a story from the next generation’s point of view, to stay there and not be diverted into the big, overshadowing parental one.

I joined the Auckland Second Generation Group over 20 years ago. There are groups all over the world, great numbers of them in the US. It was a surprise to me that there were other people who saw the barbed wire behind the eyelids. My father hadn’t been in a camp, but I still had the horrors.

My father didn’t weep but neither was he the silent survivor: his stories were insistent, repetitive and not always true – later I understood them to be symbolically apocryphal. He would say, “Your grandparents were loaded onto cattle trucks and sent to the gas chambers,” and as a child in Tauranga 1963, it was a terrible thought. No one else’s grandmother was a slave. I felt really bad, and somehow guilty – as children do – that I was okay, that it didn’t happen to me.

I recently sat in the car listening to a radio interview, unable to get out until it finished. It touched on an experiment where mice were put among beautiful, scented cherry blossom, with electric shocks applied to their little feet. The mice offspring and their offspring’s offspring, whenever exposed to the almond-y scent of cherry blossom, reacted with fear and stress.

The woman on the radio wondered why scientists had to torture mice to prove that transmission of trauma was genetic.

Later I found the research and the scientists claimed the shocks were mild. I was kind of glad that there was proof of the inheritance of trauma, that we weren’t making it up.

Scientists don’t have to apply electric shocks to my feet. Just thinking about torture and medical experimentation makes me fearful and stressed. I’m a lifetime donor to Amnesty International, Greenpeace and Oxfam. I may be overly sensitised to suffering, and I have a strongly developed social conscience. The donations are also something of an insurance policy, in case it ever happens again.

In case they come for me too. The list, the knock at the door, the disappearance.

The Sound of Breaking Glass by Kirsten Warner (Mākaro Press, $35) is available at Unity Books.