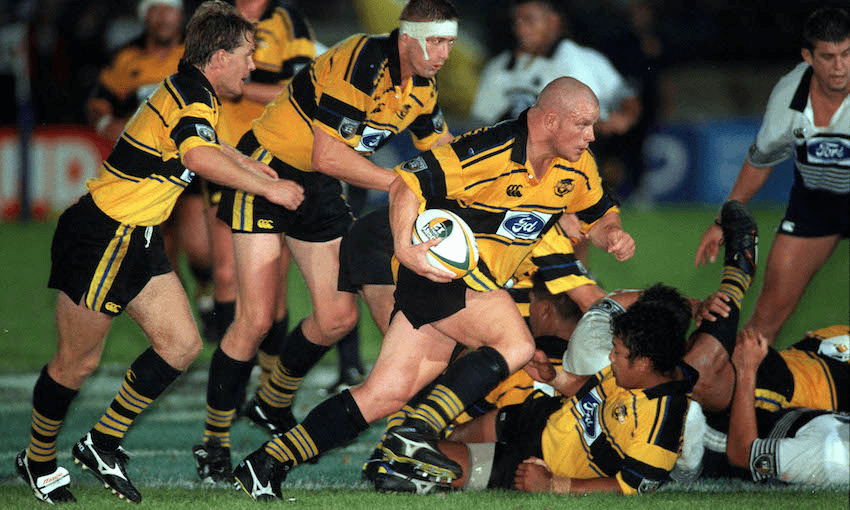

Veteran Herald sports reporter Wynne Gray has written a new book about what happens to rugby players when they hang up their boots. In this excerpt, Mark “Bull” Allen – the All Blacks prop who led the Hurricanes in the Super 12 in 1996, and played 110 games for Taranaki – tells his story.

The end came in a scrum against the Brumbies in 1998 in a match I probably should never have started. My back was buggered.

I’d been fortunate to play in both the amateur and professional eras at my peak, and it looked like I was going to be a regular in the test team. Everything was lining up, but my marriage to Geralyn was just about stuffed because I was never home. Rugby took me away all the time and in those early days of professional rugby as captain of the Hurricanes, even if I wasn’t playing I was promoting the team.

When I finished, I felt like I could have played a lot more games for the All Blacks and I felt I had failed. Blessed with success, but cursed with ambition.

I felt like I never quite achieved what I could have. I thought I could play more tests, but the question mark was always around my scrummaging. I was very visible doing other things around the field, but there was a perception I couldn’t scrum. I had a few challenges as I had started as a prop late in my rugby career at 19, although I felt by the time I finished I had sorted it out. It’s all about timing. Someone like Duane Monkley springs to mind; he could have been a wonderful All Black, but he didn’t get the nod in his era.

At the time, the All Blacks had captain Sean Fitzpatrick, Craig Dowd and Olo Brown as a collective and they were the best front row in the world. It was as simple as that and it didn’t make sense to break them up. I remember playing in the trials and getting to go alongside Fitzy and he was such a terrific scrummager.

There I was with my life at a crossroads with three young kids at that stage, a wife who’d had enough, and a decision had to be made. I thought if I continue playing — my back was giving me grief — did I want to be crippled by the time I got to 50?

I’d trained as an auto electrician and loved working for my father in Taranaki, but there wasn’t really room in the business for me as well. We were living just out of Stratford and we decided if we were going to make a change we should go somewhere different, so we moved to the Bay of Plenty, to Omokoroa on the edge of Tauranga where Geralyn’s parents had a property.

I had a bit of money from professional rugby and Geralyn had studied for a law degree, then went back to run the family sheep and beef farm when her father got sick. She was keen to continue farming, but that wasn’t me, so we went into kiwifruit.

We lost heaps of money. We made a couple of bum calls and lost about a million bucks. At the same time, we were building a house in Bethlehem in Tauranga that was going to cost us $400,000 so I needed an income. At one stage during the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, I was working in four different jobs — with night shifts and long hours – and also sat my real estate licence. I worked for a travel company and then a media company in Auckland.

Geralyn finished her degree and worked part-time, so we could keep our kids at Bethlehem College. We both have a strong faith, and when we were struggling, our faith and church family helped us get through it. My parents helped us keep our kids in the school they were used to, by paying fees, and my in-laws were great too with their support, so we were very fortunate.

It was hard to ask for help and your pride gets a hit and you feel a bit of a failure after being reasonably successful. Now I know I can speak to my kids about what life is like on both sides of the fence, and they see me getting up early, going out the door to exercise or to work every day and that’s a strong message about attitude and work ethic. Things like financial turmoil can blow you apart, but it drew us together and made us realise how lucky we were to have each other and our health. We all need to believe in something and our family has a strong faith in God. We got advice for our investment plans, but they still didn’t work out.

One day I was watching Luke, my oldest son, play rugby and I don’t know what it was, the Holy Spirit or a voice or whatever, but the thing that came to me was — would you be any happier now if you had all that other stuff? The simple answer was no. I realised I had been chasing things thinking that would make me more successful, but I had been chasing the wrong things. You don’t know you are doing it, but you are. I had a healthy marriage, healthy kids, I was still employable and fortunate I had a work ethic — and all that was worth a fortune.

At one point, I was working at night for a mate’s building company. I’d done promotions with Christian Cullen in a supermarket and there I was, in a hi-vis jacket and helmet putting up shelving in the same place . . . and no one cared.

Mahe Drysdale came along one day. He looked at me and said, “Is that you, Bull?”

He jokingly said, “Things must be tough, Bull.”

I said, “Mahe, it’s kind of you to stop and talk to me because lots of others don’t bother.”

He replied, “Bull, I’ll talk to you, but I’ll have to send you an invoice.”

What a down-to-earth, good guy.

Fortunately, I got asked by one of my son’s friends to speak at a function for Genera Ltd, and that led to a job. They’re a company which uses heavy-hitting fumigation for import and export goods such as logs and containers. Head office is at Mount Maunganui and they were rebranding the pest-management division. I was looking for something local and started as business development manager. There were five of us on staff then and the business has grown and now has 30-odd staff including subcontractors — and these days I manage the business. Rugby opened that door for me and I was able to walk right through that opening.

We run a big bus, with four kids still at home and my mother-in-law living with us too. I’m coaching footy teams. I’ve coached the older boys who are 17 months apart and both played for the under-18 Bay of Plenty team the same season. I’ve coached Tai Mitchell, which is a rep team in the Bay that my youngest fella is in, and now he’s in the Roller Mills Bay of Plenty Primary School team. He’s a hooker and he goes well.

I haven’t had a drink for years. It had to stop. I remember coming back from one rugby trip when I missed a flight and Geralyn picked me up and said, “If you expect me to keep making excuses for you to your kids, I’m not going to any more. How is it you give your best to others and can’t give us the same attention?”

Life’s been better since then. I love playing tennis, which I’ve picked up again after playing as a youngster, and a mate of mine has a ping-pong table and we get into great matches there. I swim and I’m into working with kettlebells and then into the sauna to stretch and recover. I’m enjoying every day as it comes.

Extract from Rugby: The Afterlife by Wynne Gray (Upstart Press, $39.99), available at Unity Books.