Lo, another beautiful book from Te Papa Press! In The New Photography, Athol McCredie traces the memories and modus operandi of eight New Zealand photographers who, in the 1960s and 70s, pushed our photography into the realm of art.

We dithered for days over which to feature here: John Fields, and his images of East Cape and Oneroa? Ans Westra? We loved a Len Wesney shot of a man sleeping on the Cook Strait Ferry; we loved Richard Collins’ images of sand, toetoe and topless bodysurfing at Pakiri.

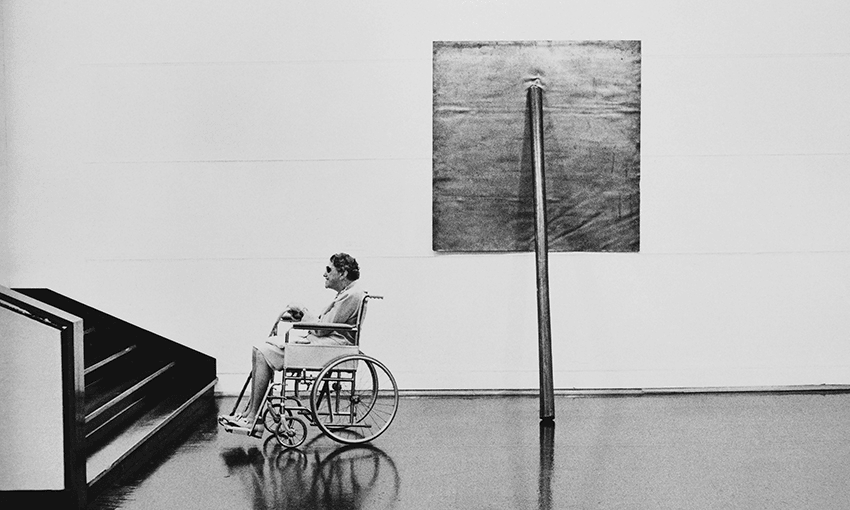

But John Daley clinched it with this image of a woman stymied by stairs at the Auckland City Gallery. You get the sense that the moment after the photograph was taken she simply raised an eyebrow and floated up those stairs by sheer strength of will.

Here, an abridged version of John’s chapter.

On a Friday night I’d catch the train into Wellington from Lower Hutt and I’d just shoot to all hours of the morning, until there was nobody left on the streets. I’d wander. In those days I can remember wandering backstage at a SEATO [Southeast Asia Treaty Organization] conference with probably all manner of incredibly important people there. Security didn’t seem to be a big deal. I wandered upstairs at a ballet and there’s the governor-general and his whole entourage having drinks, so I popped off a shot or two of them doing that. Nobody stopped you in those days. You wouldn’t get near them now.

I was walking down Queen Street one day in Auckland, and this Jaguar or Rolls-Royce was at the roadside. A chauffeur opened the door and Edward Heath, who was the prime minister of England and on a state visit, popped out. He saw me with a camera and he did this great pose. I just stared back. I thought, ‘I really don’t want to photograph you,’ and I didn’t take a shot. I think he was quite perplexed. I couldn’t see a shot there so I didn’t take one. Film was expensive, too, and I wasn’t earning much. I was pretty lean on how much I shot.

I got to the stage of visualising things even when I didn’t have a camera with me. I’d see everything through a camera frame. Click, click, click. It sometimes even had the little exposure needle thing on the side of it. And when I did have the camera on me, using it became automatic. I’d walk out from under a shop veranda and I’d reach down my hand and close the aperture on the lens down a bit because the light was brighter. After crossing the road and under another veranda I’d put my hand down and open up the stops again. I became adept at that. I always seemed to get pretty bang-on exposure. The camera literally became part of my body.

I was striving to create a cross-section of a city community going about their life. I wasn’t trying to create great art or anything like that. I was just trying to document what was happening. I don’t think it was more than that. I was trying to get quirky photos. I liked to see people doing interesting and unusual things. There had to be something interesting there – whether it was signage, whether it was the way people were relating to each other, their body language.

It was really my curiosity about people. I’d come from Tauranga, which was small then, and I’d lived in small towns all my life. We were constantly shifting from one small place to another. I can still remember being on the train coming into Wellington, the excitement of that vision over the harbour. It was a gorgeous day. I thought, ‘This is for me. I love it.’

But really, the rationale in many ways was that I was quite shy. I was an only child of elderly parents and I didn’t know very well how to relate to people. People were a curiosity to me. Photographing was my way of observing the world and working out how things ticked. So a lot of what I was doing was observing these strange rites and rituals of city folk and how they went about their lives every day. I found it absolutely fascinating.

And of course with the sort of photography I was doing, you can’t go up and say, ‘Oh you are looking great, can you do that again so I can photograph it?’ You have to grab the moment and photograph it when it’s happening. And the bulk of the people, certainly for the first couple of years, never knew they were being photographed at all. I devised this technique of judging how far away someone was and standing facing a totally different direction, measuring out my focus and things, and then just swinging around, taking the shot, and carrying on, always looking in a different direction, avoiding the gaze. Sounds rather cowardly, but it was my way of doing it.

I’ve always been quite keen on danger. I’m a risk-taker in life. Fortunately I’m still here. That developed, and as I became more confident I would go up and say, ‘I hope you don’t mind, I just took a shot of you and this is the project I’m doing and blah, blah . . .’ People were generally perfectly happy with it. Street photography was much easier in those days. I’d get my head chopped off now if I did some of the things I did then.

Extracted with permission from The New Photography: New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers, by Athol McCredie (Te Papa Press, $75).

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.