Herald police reporter Anna Leask takes a look inside women’s prisons, in this powerful excerpt from her new book Behind Bars.

When they locked her up for the first time her baby girl wasn’t even two months old. The day she went to court for sentencing she couldn’t bear to bring her daughter with her. She didn’t want her last goodbye to be fraught and emotional; she didn’t want to break down and scream for her baby as they led her out of the dock and into the cells. So she got up that morning, fed the baby and put her down to sleep in her cot. As she walked out of the room she stopped and looked back at the girl, her tiny body wrapped up warm, the blankets moving as she breathed and her little face so peaceful. She took a deep breath, turned around and walked out of the room, the house and out of her baby’s life for God knows how long.

Hours later, Elaine Ngamu, aged 20 and a mother of two, was sentenced to prison for fraud. She’d been caught using stolen credit cards and pleaded guilty at the outset — she knew she’d done wrong and she wanted to get the punishment over and done with so she could focus on her children. But it hurt so much being away from them, not being able to cuddle her baby girl or kiss her three-year-old son. It was a pain she still has trouble finding the words to describe. At Mt Eden they asked her if she was still breastfeeding her baby. Yes, she said. They asked her, in a way that put utter fear into her, if the baby would be in “danger” staying at home being bottle-fed.

“No! She’ll be fine,” Elaine told the guards, convinced that if she said the opposite the kids would be taken away from her partner, shoved into foster care with strangers.

It was the wrong answer. If she’d said she wanted to keep breastfeeding she would have been kept in Auckland, the baby brought to her a few times a day. She would have had regular contact with her infant. Instead, she was on the next flight to Wellington to do her time at Arohata Prison, 650 kilometres away from everyone she knew and loved.

Elaine said: “It was so horrible. My daughter had a gastro problem for about three weeks just before I went into prison. I kept having to rush her to the doctor . . . I was fortunate that my family stepped in to look after her, but I just spent all my time worrying.

“Going to Arohata made things really hard. I got a phone call twice a week but you never knew when it would come. They would just call out, ‘Right, all the Auckland girls, you’re getting a call,’ and we’d have to queue up and wait. I would just hope like hell someone would answer at home so I could speak to them, make sure the kids were alright.

“My younger sister moved in and she cared for the baby. She was pregnant at the time, and it was so traumatic for my baby that when she had hers, she gave it to another sister to look after and she stayed at my place with my daughter.

“My partner was also there, looking after the kids, and he would bring my three-year-old down to visit me a couple of times a month. I was one of the lucky ones in prison. I knew that they were all OK and I only had to look after myself, keep myself alive. But I still missed them like crazy.”

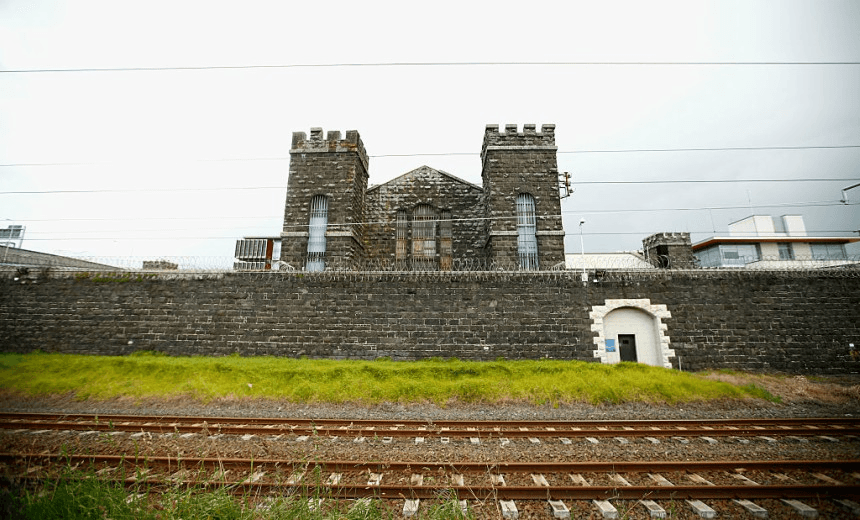

New Zealand’s female inmates — many of them mothers — are housed in three facilities in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. It wasn’t until the 1940s that women were separated from men; before that it had been argued that there simply weren’t enough female inmates to justify gender-specific jails. In 1914 a section of Addington Prison was dedicated to women only, and reform facilities for girls followed, with Point Halswell in Wellington in 1920 and Arohata Girls’ Borstal in nearby Tawa in 1944. The latter would later become the current Arohata Prison — its name, meaning “bridge”, reflecting a hope that the facility would, in the city council’s words, “provide a bridge between past offending, and a future life in the community”.

Mixed prisons continued to operate until the opening of Christchurch Women’s Prison in 1970. Women from across New Zealand were sent to Christchurch to do their time.

At the time of writing, Christchurch has about 115 inmates, Arohata 90, and the recently opened Auckland Region Women’s Corrections Facility 467. All three prisons now offer programmes specific to women, and, unlike when Elaine Ngamu did her first lag in 1989, they have mother and baby units on site to accommodate inmates jailed while pregnant, as well as others with newborn or young babies (up to nine months of age) at the time of sentencing.

Actually, a lot has changed in women’s prisons since Elaine’s first stint. Back then, for instance, there were no toilets in cells — inmates used a bucket overnight that they had to empty each morning. In 1998 Elaine returned to prison to do another stint for fraud, but it took her a while to get there; Arohata was too full and there were no beds free. So she was sent up the road from the courthouse to the Auckland Central Police Station, where she ended up staying for three weeks. Until then she thought the conditions in prison were rough.

She arrived, went through the check-in process and was led to her cell, and given a thin grey blanket. She dreaded the arrival of night, when the cold would seep into the concrete walls, through the bars of the cell door and into her bones.

The cells are underground, with no windows, so you don’t know if it’s day or night. The only way of telling the time is by what meal (if you can call it that) is served. To this day they remain exactly as Elaine described Auckland Central: “Horrible dungeons under the city.”

Behind Bars: Real Life Inside NZ’s Prisons by Anna Leask (Penguin, $40) is available at Unity Books.