Vana Manasiadis wrote a collection of poetry in the wake of her mother’s death. In this essay, ahead of her appearance at the Going West festival, she argues that as a nation Aotearoa needs to learn to make space for mourning.

When Mum died in Athens, I cried loudly and publicly and was held up by strangers. I took part in death customs that spanned days, then weeks, then years. I talked (and talk) to Mum without being pathologised, and dealt with the complex to-ing and fro-ing of her bones.

I’m a Greek New Zealander, but up until that time, and especially during, I would have said Greek only. Because how could I have been a New Zealander when Mum was regularly othered by other Pākehā and told to go home? More especially, how could I have been a New Zealander and grieved the way I did?

The narrow type of New Zealander in my head didn’t grieve so wholly. Instead that person might have said ‘I’m OK’, or ‘she’s right’, or ‘all good’; might have been embarrassed by displays of emotional pain and joked or apologised them gone. (How many funerals had I been to – for example – where the eulogists were congratulated on keeping it together?). This is how I saw us grieving – or not grieving – in New Zealand.

But in the four years since returning from Greece (and four months since the Christchurch killings), I’ve come to see three things: that there’s no one, normal, default type of Kiwi; that loud, bodily, immersive grief is not just Mediterranean, or Eastern, or foreign-old world-tragic-gothic; and – most importantly – that there have always been better ways to grieve in Aotearoa New Zealand.

At my brother-in-law’s grandmother’s tangihanga (Ngāti Kahungunu o Wairarapa) at Te Marae o Kohunui, ngā karanga, ngā poroporoaki, ngā waiata tangi were sacred and positioning and shared. There was wā for mourning and contact, a time and space into which the departed were invited and addressed. And suddenly I could say nō Te Whanganui-a-Tara me Atene au and really mean it – because I’d found the right language and witness for my own grief (here all along).

And this has led me to thinking about the place of ceremony and witness. About how collective mourning allows us to speak grief, and gives us the chance to see and to carry each other. About how expressed mourning resists pretence and inhibition and secrecy. It’s pretty obvious. But do we have enough of these opportunities and mourning spaces?

Because in the meantime, here are two realities:

- Our mental health statistics are awful, our suicide numbers, especially for Māori, are shameful.

- We haven’t been grieving, as a people and a country, the horrific realities of our history.

And it’s hard not to wonder about a connection. If we aren’t mourning our national tragedies, how can we be a culture sensitive to grief, to the grief of others, to our own? How can we move towards healing? The bloody history of Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa The New Zealand Wars, the fact that we live down streets called after perpetrators of colonial injustice – we are commemorating the wrong things at the cost of the right ones.

And commemorating the wrong things has costs. Violence and injustice are memorialised and are coated in normality. Normality makes it way too easy to turn the other way and not to recognise or address pain (community and therefore, personal). Our national grief response to the Christchurch killings proved that collective mourning for acts of hatred committed here is possible, but we should also call out other acts of supremacism that have hurt our generations – and our record on this is the pits.

So we clearly need many more wā to be able to this better.

Like, for example, replacing Guy Fawkes with Te Rā o Parihaka, a national holiday on November 5th. Both Marama Fox and Marama Davidson have championed this because clearly, we should all care more about Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi, and their peaceful resistance to invasion in 1881 (that Chris Finlayson, Treaty Negotiations Minister in June 2017, called “among the most shameful in the history of our land”), than about what this guy Guy Fawkes did in England in 1605.

Yes, we could pretty much introduce any number of days to commemorate any number of violations: Te Rā o Waikaremoana, Te Rā o Waitara, etc, etc. The violent mistranslations of Te Tiriti could prompt a National Language Aggression Awareness Day, or Treaty Breaches Awareness Day, or Land Confiscation Awareness Day (see Ihumātao). Because that’s how dealing with grief works – you have to really stare it in the face. Again and again.

But I’m not saying this any better than Safari Hynes did in June: memorials speak. And all kinds of memorial offer us chances to bear witness to loss. After Mum died, I’d go to Estavromenos church on Soul Saturday, though I’m not religious, and stand beside other weeping folks grieving for people lost years before, or generations earlier. I’d stand next to the plaque to resistance fighters killed in the square outside and remember Mum lost to immigration, or my refugee grandfather lost to home.

That was Kirihi Greece. This year I was here in Aotearoa during Mum’s anniversary, and it was Matariki. It was also the year Eleni, my precious nine-year-old friend, chose Mum as her Pōhutukawa star, the star that carries the dead across the year, and let a candle float across the water during her school’s trip to Te Papa. So tell me again: with more and more people learning about and celebrating Matariki, why do we have a holiday to celebrate the British Queen’s Birthday when we could have a national Matariki holiday instead?

Because these things are choices – like the choice I’d made not to be Kiwi when I didn’t feel reflected, and the choice I made to stand here again when I did.

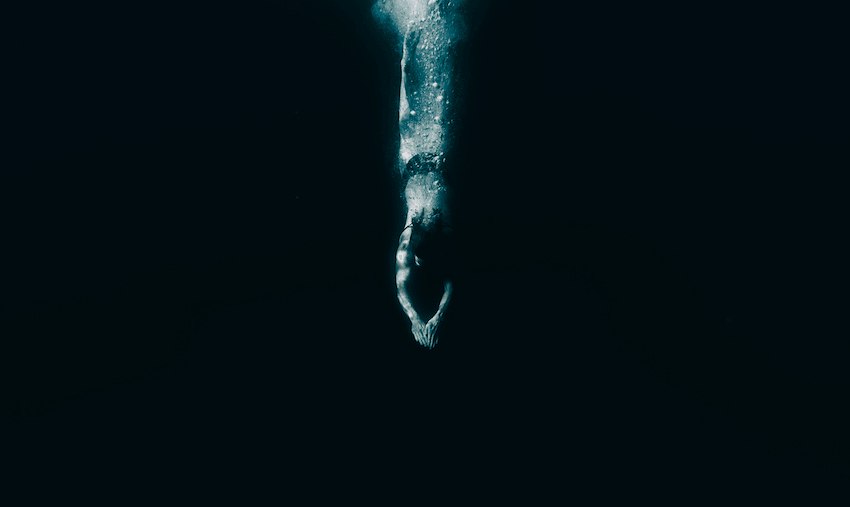

There’s a phrase in Greek, βυθίζομαι στο πένθος, I dive into grief. And we don’t have a choice but to dive into this whenua’s history, the consequences of that history, its tikanga, wounds and many resiliencies. Because we really do need to start speaking grief better and getting better and being better. It’s about manaaki. And wairua. And it’s been urgent a very long time (and space).

Noho ora mai rā i roto i ngā manaakitanga katoa.

Vana will be in conversation with Kiri Edge (Ngāti Maniapoto), Emma Johnson and David Slack at Going West’s ‘Writing the last page‘ on 8 September 2019.

The Grief Almanac: A Sequel, by Vana Manasiadis (Seraph Press, $30) is available at Unity Books.