No other road in New Zealand is as rich in history, suffering, war, immigration, hope and hard, hard work as the Great South Road that joins Auckland to the Waikato. Scott Hamilton walked its length and felt its pulse.

For the last five years I’ve travelled the Great South Road. My journeys have been spasmodic, erratic, circuitous. They began when Paul Janman asked me to help him document the road and its history for a film and a series of art shows.

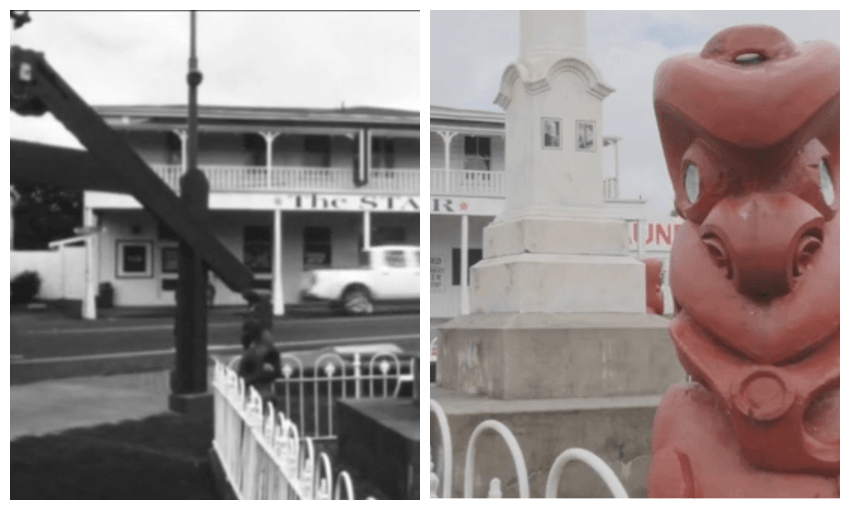

Paul and I travelled up and down the road on foot, in cars, on buses. We found the lights of all night garages burning on the ruins of British redoubts, hamburger bars leaning on the eroding earthworks of pā, pensioners raking leaves from front yards where Tawhiao’s warriors ambushed armed convoys. We interviewed local historians, graffiti artists, arborists, publicans. We also began a second, parallel expedition, along a paper trail provided by the libraries and archives of Auckland. We wandered old papers and magazines, collected reports of battles and strikes and festivals. We squinted at posterised photographs. The people we met in the archives often seemed as real, as vivid, as the men and women we encountered on the road.

In 2015 Len Brown gave me the inaugural Auckland Mayoral Literary Grant to help me write about the Great South Road. At the end of that year Paul Janman and I walked 200 kilometres along the road, from the Puniu River to downtown Auckland. We were greeted at the Puniu by television and radio journalists; they broadcast news of our own trek, so that over the next few days passing motorists beeped or abused us, and farmers bought us beers in the pubs where we rested.

As our investigations of the road continued, we began to give talks to local history societies, and at libraries, and to show photographs and short films and historical objects in art galleries. John Hurrell, the indefatigably curious editor of the arts journal Eye-Contact, sent me down the road to review exhibitions in suburban galleries. Paul and I showed a crowd at the Auckland Writers Festival close-up photographs of the blisters that had grown like barnacles on our feet during that long walk up the road. Wherever we went, and whenever we showed our work, people wanted to share their own stories of the road.

Ghost South Road from Public Films on Vimeo.

On January 1, 1862, soldiers of the British Empire began a road that would connect Auckland with the Mangatāwhiri River, which the Māori king Tawhiao had proclaimed the northern aukati, or border, of his realm.

The soldiers sawed and burned a way through forests of puriri and rimu, flattened and shaped the exposed earth with picks and shovels, and metalled the road by breaking volcanic boulders. In clearings up and down the road trenches were dug, barracks were raised, and soldiers stood on sentry duty. By the end of 1862 a huge fort had been established at Pokeno, close to the northern shore of the Mangatāwhiri. It was called Queen’s Redoubt.

Great South Road was built because colonial businessmen and politicians in Auckland wanted war, and because Governor George Grey shared their desire. King Tawhiao had banned his followers from selling land, frustrating would-be farmers who had stepped off ships from Britain expecting to have their pick of the fertile acres of the Waikato.

Instead of owning the Waikato, the new arrivals had brooded in Auckland, and eaten the food – bread, peaches, apples, fish – that Tawhiao’s people produced in the fertile south.

On July 12, soldiers marched out of Queen’s Redoubt and crossed the Mangatāwhiri in whaleboats they had dragged down the Great South Road. The Waikato War had begun. At the great pā of Rangiriri, between the Waikato River and the swamps and lakes of Waikare, the invaders charged again and again at Māori marksmen, while artillery batteries and ironclad riverboats fired in support.

Tawhiao’s army retreated into the central Waikato, and then to Orākau, a hastily dug set of trenches on the edge of the Puniu River and the region of hills and mountains that has become known as the King Country. The defenders of Orākau fought until the last bullet, then loaded plum stones into their muskets, then fled across the Puniu. For two decades, the King Country would be an independent state, where Tawhiao and many of his people lived in exile.

The invaders confiscated one and a quarter million acres of the Waikato’s best land. The Great South Road was pushed south, through the earthworks and urupa of Rangiriri, so that soldiers could settle on the earth they had conquered. The road went through the soldier-settler towns of Hamilton, Te Awamutu and Kihikihi, to the Puniu River.

But few of the soldier-settlers could make a living on the small plots of land the colonial government had given them. Most of them sold their holdings for a few shillings to the same politicians and businessmen who had started the war. Only in the 1890s, when the beginning of refrigerated shipping had made beef and dairy farming profitable in the Waikato, and Gujarati and Chinese arrivals had created new vegetable gardens, did settlers begin to prosper.

In the first decades of the twentieth century a network of stockyards and abattoirs spread along the Great South Road. Drovers brought huge herds out of the Waikato to be slaughtered and shipped to Europe. Other industries grew around the abattoirs. Landless Māori came north to take factory jobs, and were joined by the grandchildren of soldier-settlers, as well as new immigrants from Britain and Dalmatia. The workers formed unions, and the suburbs of South Auckland became fortresses of the Labour and Communist parties. A photograph from 1936 shows Michael Joseph Savage, the first Labour Prime Minister, addressing a huge crowd of workers at Ōtāhuhu’s Railway Workshops, a few metres from the Great South Road. The workers have climbed onto the rooves of railcars to see Savage; he faces them in the same wary way that the consuls of ancient Rome faced the crowds of plebeians on whose support they relied.

After World War II, South Auckland continued to grow. Tens of thousands of workers arrived from Pacific Islands like the Cooks, Samoa, and Tonga to work in new factories. By the 1970s they were living in large numbers along the road, and raising their own kava halls and churches. They were joined by migrants from India, China, the Middle East, Africa and South America. Today Auckland is the most diverse city in the world, and South Auckland its most diverse region.

The story I’ve just told is true. But so is this one, which was given to me last year, by a woman who works at two different jobs in two different parts of Auckland, and drives up and down the Great South Road between them:

It is like there are different roads at different times. In the morning, driving through heavy traffic, the road seems narrow, cramped, claustrophobic. I feel anxious, stuck at the lights, counting the minutes.

But then in the evening, after rush hour, driving home, especially when it’s been raining, the road seems like it’s been made just for me: it’s wide and empty and clean and I feel free driving it.

Here’s another story, which a reader emailed to me four years ago:

I remember how the Pacific Island kids that went to private schools would meet up at Ōtāhuhu Bus Station. We’d all hang out there, Samoans, Tongans, everyone, sharing stories of parties and plans for the weekend, all together, and then we’d split up, each group of us catching a different bus, depending on which uniform we were wearing, some going into town to St Peters, some to De La Salle, some east to St Kents. Whichever school we went to, we knew we’d be in a tiny minority. But at the bus station, for a few minutes, we were a crowd.

And here’s a fourth story, which I was told on Twitter last year:

I hate the Great South Road. It is part of colonialism and the theft of our lands. I try to travel on a different route if I am going south. I would like the road to be destroyed.

I grew up on a farm in Drury, a couple of kilometres from the Great South Road. From the tree hut I built in our tallest macrocarpa, I could see the snub nose of a volcano in the south. It was the site of Te Maketu, the pā where Tawhiao’s guerrillas had aimed spyglasses at colonial wagons moving far below them on the Great South Road.

One day in 1983, my Standard Two teacher at Drury School took me and my class outside, and made us stand in the hum and dust of the Great South Road’s logging trucks and petrol tankers. Miss McEwan pointed out a chunk of wood that leaned on the school’s sagging wire fence, and explained that this unimpressive artefact was one of the road’s military mileposts. Sometime in the winter of 1862 the posts were cut artlessly from native trees, splashed with white paint, and pounded into the mud, to mark the road’s progress towards the frontier of Tawhiao’s kingdom.

Like medieval theologians disputing some indeterminate event in the irretrievable life of their saviour, colonial historians have argued about the role and meaning of the mileposts. Were they raised so that the imperial authorities paying for the construction of the road could calculate their costs precisely? Were they intended as aids to the lonely men who built and manned toll booths on the frontier road?

Or was their meaning symbolic? Were they the architectural equivalent of a promissory note, harbingers of the forts and taverns and courthouses that were coming to the Waikato Kingdom?

As a kid I would catch a Cityline bus up the Great South Road, past places with strange names like Ōtāhuhu and Wiri, to the movie theatres, spacies parlours, and comic shops of central Auckland. Later, as a teenager, I’d make the same journey to the bars of the central city on Friday and Saturday nights, returning with a turbulent stomach on the eleven-thirty bus. Eventually I enrolled in university, and moved permanently up the Great South Road.

Because of this personal history I have sometimes seen a journey away from the city down the Great South Road as a journey into the past. As one suburb gives way to the next I recognise places of significance, and these historic sites become more and more frequent the further south I get. It is as though some film of the past is playing backwards.

Over the past five years there has been a revival of interest in the Waikato War, and in the tragic history of the Great South Road. In 2013 thousands of people gathered at Rangiriri to mark the sesquicentenary of the war’s bloodiest battle; in 2016, after a campaign spearheaded by students from Otorohanga High School, the government agreed to make October 28 a day for the commemoration of the Waikato War and the other New Zealand Wars; and in the same year Vincent O’Malley published, to acclaim and to the consternation of conservative Pākehā, an angry and carefully detailed account of the Waikato War and the confiscations and protests that followed it.

I rejoice at the growing recognition of the Waikato War and its aftermath. I look forward to the day when the battle of Rangiriri is as famous as Gallipoli, and when Pākehā New Zealanders recognise the confiscation of the Waikato as the crime upon which their country’s dairy industry has been built.

This edited extract is taken from Ghost South Road by Scott Hamilton (Titus Books), available from Unity Books.