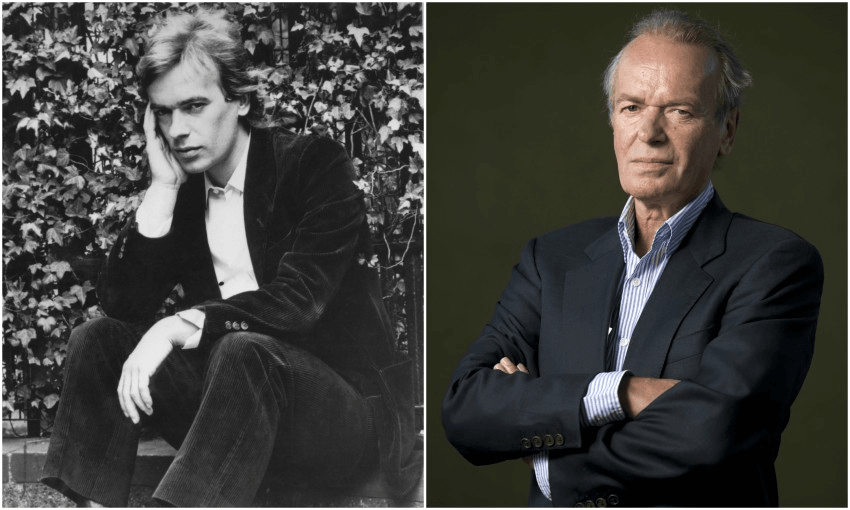

Philip Matthews on the Alanis Morrissette of literature – yelping, abrasive 90s has-been Martin Amis.

The 1990s come flooding back as you read The Rub of Time, a collection of essays, features and reviews by Martin Amis. It’s so 90s it should require a soundtrack by Alanis Morissette or the Cranberries. Was there ever a more 90s journalism assignment than the time the New Yorker sent Amis to Hollywood to profile John Travolta during that brief, promising moment between Pulp Fiction and Get Shorty? Is there a more 90s image than Amis getting a fax – yes, a fax – to his hotel from Will Self, while on an author tour he is writing up, again for the deep-pocketed New Yorker?

He was at the height of his powers then. Just as Travolta was between Quentin Tarantino and Elmore Leonard, Amis was between Visiting Mrs Nabokov and Other Excursions (1993) and his last great novel, The Information (1995). Is it bracing to think that more than 20 years have passed since Amis last wrote a novel that was worth getting to the end of? I tried them all: Night Train, Yellow Dog, House of Meetings, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo (hopelessly subtitled “The State of England”) and The Zone of Interest. The last of those might be the most tone-deaf Holocaust novel this side of The Kindly Ones.

Why did so many of us keep trying? Because you hoped again for that rush or buzz of Money, London Fields and The Information, that confident, arrogant style, that audacity and cruelty, that ripeness. He wrote such terrific sentences. But the books are stuck in their time, in a Britpop age of tabloid frenzy and writer celebrity. They feel like artefacts of their own media coverage rather than books you would actually pick up and read. Reading Amis’ Time magazine obituary of Princess Diana in this new collection – “a mirror, not a lamp … a prima donna … a collateral celebrity” – made me suspect that I was, in some strange way, reading Amis’ obituary for himself.

All this is germane to The Rub of Time (subtitled “Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump and Other Pieces, 1986-2016”) because these pieces reveal an obsession with posterity. Will he last? Will they read him in the future? The questions must nag at him because he asks them about almost every writer he covers. He believes that “Judge Time” will decide if Philip Larkin remains a major poet. A review of Don DeLillo stories opens with a long prologue in which Amis quickly assesses the complete works of Joyce, Kafka, Dickens, Shakespeare, Proust and Austen and concludes that “we love about half of it”. In another piece, he ranks the Nabokov novels: only Lolita, Pnin and Despair are “immortal”, along with four or five short stories.

We all want immortality. It would be cheap and easy to say that Amis, now 68, is writing with his own mortality in mind, that these are end-of-life judgments from a twilight land. But some of these pieces go back 10 years or more and such big-picture career assessments have been typical of Amis’ confidence throughout. That said, it is almost touching to see that Amis will occasionally walk back some of his Olympian statements. In one of three reviews of Saul Bellow collected here, he dismisses other great American writers in a series of asides, such as “the multitudinous facetiousness” of Herman Melville (see also “the melodramatic formularies” of Hawthorne and “the murkily iterative menace” of Faulkner). Amis and his thesaurus may have dispatched Melville in just two words in 2003 but in a postscript added for this collection, he admits that he actually went back and read Moby-Dick after nearly 50 years and (nice image) “spent a month of last summer slowly shaking my head in gratitude and awe”. If it had more of America in it, and some women, it would be a strong contender for the Great American Novel, Amis decides. Melville must be relieved.

“Age waters the writer down,” Amis says in another career-summarising moment. “The most terrible fate of all is to lose the ability to impart life to your creations.” He gets to the same point in a different way in one of his articles on Nabokov: “Literary talent has several ways of dying. With Joyce and Nabokov (and with others), we see a decisive loss of love for the reader – a loss of comity, of courtesy.” Even a piece about tennis is really a piece about ageing, about losing one’s powers: “A beautiful game, but one so remorselessly travestied by the passage of time.” And to be an older writer is to risk becoming irrelevant and invisible, as he noted in a piece written in 1995 when he still called himself a younger writer: “Older writers should find younger writers irritating, because younger writers are sending them an unwelcome message. They are saying, ‘It’s not like that any more. It’s like this.’”

At some point, Amis became more interesting as a non-fiction writer than as a novelist. When was that? If you remembered that the 1995 peak was book-ended by Visiting Mrs Nabokov and Other Excursions (“excursions” is such an Amisian word) and The Information, then it was clear that the novels were still the core business, and collections of reviews and journalism were filler, a side project. That probably changed with the memoir Experience in 2000, which had all the heft and electricity of London Fields or Money, and the no less monumental collection The War Against Cliche: Essays and Reviews 1971-2000 that appeared a year later. In the decade after, Amis followed his pal Christopher Hitchens onto the opinion circuit and there was a poorly received book on Stalinism (Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million) and the inevitable book on militant Islam (The Second Plane). Both brought him the kinds of headlines he used to get for his novels, and not always in a good way.

His reputation as a novelist took a hammering in the same decade. Tibor Fischer famously wrote that Yellow Dog is so bad it is “like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating”. Wikipedia calls that “one of the most quoted statements in a book review of modern times” and there is a real possibility that the quote will outlive both Fischer and Amis, speaking of posterity. Amis tackles the controversy in an ask-me-anything Q and A that originally ran in The Independent. When a reader named Richard asks which of his novels is his favourite, Amis goes straight for Yellow Dog: “My fellow novelist Tibor Fischer contributed a gun-jumping hatchet job; and, after that, everyone who could hold a pen was suddenly feeling brave.” Does he really think they were scared of him before? Amis, who has wielded the hatchet more than a few times himself, goes on and on about it.

Including the Q and A could have been a mistake. It makes him look thin-skinned and defensive. Another exchange, when a reader named Jonathan wonders about Amis’ silly post-9/11 coinage “horrorism”, which did not exactly catch on, features Amis telling Jonathan to “fuck off”. Much of the journalism has not stood the test of time, but journalism seldom does. Who wants to read a 23-year-old John Travolta profile? His anecdotes become repetitive: we have heard the stories about Hitchens, Clive James and the New Statesman before. The same goes for the stories about Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin. As for the reporting, there is a feature about the porn industry that was horrible the first time round, when it appeared in 2000 in Tina Brown’s short-lived magazine Talk. A piece that celebrates Las Vegas because it is un-Islamic is mindless. We already knew that terrorism is another of those subjects about which Amis has nothing useful to say.

The cover promises some writing on Trump. The piece about the president and his mental health (“Narcissus is auto-erotic; he is self-aroused”) ran in Harper’s in 2016 when Trump was merely the Republican candidate. Rather than reporting from the trenches on the campaign trail, Amis offers a long book review of The Art of the Deal and Crippled America. Separated by three decades, the two books show that Trump, “both cognitively and humanly, has undergone an atrocious decline”. That’s insightful. More revealing still is Amis’ suggestion that when it comes to sex, he and other baby boomers he knows, including some women, “behaved far more deplorably than Trump”. This has, as they say, not aged well: the piece was written long before the Access Hollywood tape and the Steele dossier. Calling Trump “a gawker, a groper, and a gloater; but not a lecher” now seems a little weak. Elsewhere, Amis reminds us that he is not just a feminist, but “a gynocrat”, which means he believes in rule by women (Excursions in the Gynocracy – now there’s a future Amis title).

On the other side of the Atlantic from Trump, there is Jeremy Corbyn. Amis dislikes him too. He is a philistine of a different sort. A Sunday Times piece from 2015 mocks the Labour leader for being “undereducated” and “humourless”. Worse, “he has no grasp of the national character” – a line that sounds like a parody of some ancient bloviator in The Spectator. The last accusation is an especially odd one from a writer who left the UK for New York in 2012 and stayed there.

Even a piece that is ostensibly about Corbyn inevitably contains quotes from Larkin (who “spoke for the country”) and golden-age, long-lunch recollections of Hitchens and the New Statesman. If you read too many of these pieces in a row, they start to suggest a form of senility: the input grows increasingly narrow, the same stories are told and retold. The compilation of the book doesn’t help either. Besides the three passes at Bellow, there are three pieces on Nabokov and two each on Roth, Larkin and Updike.

But, taken on their own, these nuanced, full literary pieces are the best thing about The Rub of Time. Forget “horrorism” and Travolta, I only want to read Amis on writers he admires, in pieces that reveal his admiration is broad, tolerant and lasting enough to acknowledge their flaws. A story about Iris Murdoch is a nice blend of movie review, gossip column and literary appreciation. The first piece about Nabokov reveals that no fewer than six of his fictions concern themselves “with the sexual despoliation of very young girls” and the quiet outrage and disappointment that follows from Amis may be the most sincere and sustained moral position in the book (“Nabokov’s mind … insufficiently honoured the innocence of twelve-year-old girls”). Even his beloved Larkin is called an “old bore” as well as an “old bag” in a long and enjoyable review of Letters to Monica that ends with another of Amis’ reflections on posterity that surely contains hopeful predictions about his own reputation. “Larkin’s life was a pitiful mess of evasion and poltroonery; his work was a triumph … The life rests in peace; the work lives on.”

The Rub of Time by Martin Amis (Jonathan Cape, $40) is available at Unity Books.