Last week we asked New Zealand CEOs whether greed is still good. In the second part of our series on the ethics of NZ businesses, we put them on the spot over whether short term profits trump long term environmental impacts.

“If I had a choice I would much prefer not to sell fossil fuels tomorrow.”

Would Karen Walker rather not sell designer dresses? Does Xero founder Rod Drury feel disquiet over the small business software empire’s unceasing expansion?

Obviously not. But the reality for Z Energy CEO Mike Bennetts is he’s selling a product that is eroding the environment, and with a bit of luck is a sunset industry anyway.

Eventually it’s highly likely all passenger cars will be electric, while trucks will be a mixture of electric, hydrogen and biofuel-powered vehicles, he says. But that time is a way off yet. “Our day is decades away, to be honest with you.”

In the meantime the fuel retailer must dice with the double-edged sword of reducing its impact on the planet and running a profitable business.

Z could go one of two ways, Bennetts says. It could gradually transform itself into a supplier of sustainable fuel, and hence it is investing in biofuels, exploring hydrogen, and has bought an electricity retailing company. Or it could become the last man standing selling fossil fuels in New Zealand, its only market.

“But we want New Zealand to transition away from fossil fuels. I think it’s a reflection of what our employees are looking for, and what our broader stakeholder set is looking for.”

Bennetts clearly has a greater interest than most in the conundrum of climate change, but it’s an issue facing all businesses whether they acknowledge it or not.

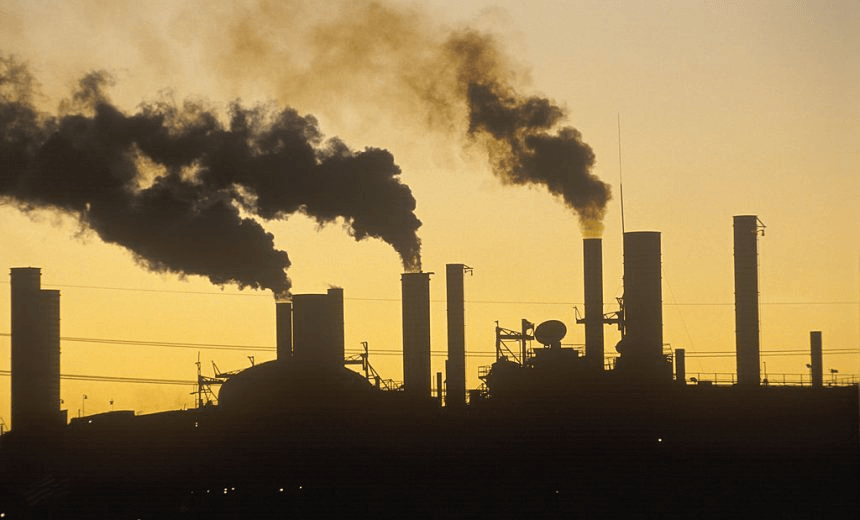

The last four decades of unfettered free market capitalism have not produced widely shared prosperity, but rather created a raft of societal problems including growing inequality and an impending climate disaster.

This in turn has beget a widespread loss of faith in the capitalist system, particularly among the next generation of customers and employees. Respondents to Deloitte’s 2019 Global Millennial Survey say climate change is their greatest concern by far, and 37% have stopped or lessened a business relationship because of the company’s ethical behaviour.

A climate catastrophe now looms so large that local and central government are placing it at the centre of their policymaking. Auckland Council has declared a climate change emergency, while the government is aiming to put greenhouse gas reduction targets into law with its zero carbon bill and has announced the country’s first Cross-Government Climate Action Plan. Even the farming sector is slowly climbing on board, with sector leaders signalling support for a special emissions levy and rebate scheme.

Meanwhile Wellington father-of-five Ollie Langridge has become the longest running protester outside Parliament, recently clocking up 74 straight days in support of his demand that the government declare a climate change emergency. He won’t leave until it does, he says.

Are businesses, some of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters, taking climate change as seriously as everyone else?

We put three key issues at the heart of the life-after-capitalism debate to a selection of Kiwi business leaders. The following are their answers to our second question:

Many people observe a tension between shareholders’ desire for consistent profits and the long-term challenge of climate change. What do you see as your business’ role in addressing this?

Alistair Davis, CEO of car dealer Toyota New Zealand and chair of the Sustainable Business Council

“As a brand that has nearly a quarter of all vehicles on New Zealand’s roads, and with transport emissions accounting for nearly 20% of all carbon output, Toyota has a significant influence on how New Zealand will progress to a zero carbon economy. This will not happen quickly. The life cycle of a motor vehicle can be up to 30 years, so a model Toyota starts planning now and introduces to the market in three or four years may not disappear from our roads until after 2050.

“The interrelated issues of emissions, fuel economy and climate change have been a driving force for our product development for 30+ years. After more than a decade of R&D we introduced our first hybrid electric vehicle (the Prius) in Japan in 1997 and to New Zealand in 2003, and we have progressively expanded our hybrid range ever since. In New Zealand most Lexus products are available as hybrid and we also have Corolla, Prius, Camry and RAV4 hybrids. We have now started selling plug-in electric hybrids, and when we are satisfied with the cost and quality of the product we will extend the range to cover pure electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles as well. This year hybrids will constitute over 15% of all car sales in New Zealand.

“This investment in electric technologies has not come cheap – globally Toyota has spent billions of dollars – but we are committed to leading the way. Our most important climate change goal is to reduce the CO2 output of our vehicles by 90% on the 2005 level by 2050. Not all of the technologies to achieve this have been developed yet and it’s a monumental task, but this is not a ‘long term climate change challenge versus short term profit’ equation – it is a sustainability imperative for all responsible businesses.

“Here in New Zealand Toyota welcomes the government’s Zero Carbon Bill and applauds the National Party’s bipartisan approach. We and other businesses need a predictable legislative framework that gives us the certainty to make investment decisions that, ultimately, will be for the benefit of our country and planet.”

Mike Bennetts, chief executive officer of fuel retailer Z Energy

“Businesses have to do two things, they obviously have to deliver short term performance, and they have to make sure the business is sustainable for the long term, economically, environmentally and socially sustainable.

“And I know because I experience it. Increasingly shareholders are focusing on what they call ESG – environmental, social governance aspects of a company’s performance, to the extent that if their compliance department says you don’t get a good enough ESG score, they cannot invest in you”

“That’s not a big thing in New Zealand at the moment, it’s a bigger thing in Australia, it’s a really big thing in Europe and the US.

“We’re a company that’s owned both in New Zealand and offshore. Our investors are looking at us saying, ‘what are you doing about getting your carbon footprint down in your operations, what are you doing to contribute to societal outcomes?’

“We score okay actually, which is kind of weird given the product we sell. But in terms of how we run our operations we are quite reasonable.

“Our big issue is the products we sell, not what we do. For example, we offset all our carbon emissions from our operations with permanent forests. We could claim to be carbon neutral but we don’t, because it gets nonsensical.

“We want New Zealand to transition away from fossil fuels. It’s about trying to understand what a low or zero carbon future looks like and what’s our role in it, without being silly about it.”

Kendall Flutey, CEO of financial education startup Banqer

“Tension between the desire for profits and purpose, whether that’s environmental or social, only exists if you let it. Shareholders can demand whatever they want from a company and we just assume they want to extract maximum profits (at all costs) because historically that has been the model. But it doesn’t have to be.

“Banqer holds profit alongside purpose, and considers the externalities when making business decisions that more traditional companies would consider purely financial calls. We’d make some decisions that our corporate counterparts wouldn’t, and we pass up opportunities they’d leap at. It really depends on what shareholders view as value, and how much of the equation they’re willing to consider.

“This mindset isn’t going to change in Fortune 500s overnight, but I see Banqer’s role in this as an educator. Like a lot of other companies we’re trying to demonstrate this alternative path that businesses can take, one that takes a longer term and broader view of the world.

“Two years ago we became a certified B Corporation and since then the number of other certified B Corporations in New Zealand has grown significantly.”

Jeff Douglas, managing director of pharmaceuticals company Douglas Pharmaceuticals

“The only thing that makes any business successful is profit, and if you don’t have profit then you don’t have a business. Businesses enhance the economy, enhance lifestyles and enhance a country’s overall wealth, and without wealth no-one benefits.

“As long as there is ethical and responsible corporate behaviour when producing profits then there is absolutely nothing wrong with shareholders demanding a profit.

“What can we do here in New Zealand while the large polluters of the world continue unfettered in polluting the planet in their quest to increase their country’s wealth?

“It is all very well for New Zealand businesses to send their production jobs up to China (which is a huge polluter) because it is cheaper – but it means they have to share in that pollution contribution.

“If consumers demand constantly low cost products they have to accept they are also contributing to the bigger pollution picture and all the damage that pollution does to the planet.

“Businesses need to decide how much profit they want to make and what you might sacrifice to get that return.”

Marc England, chief executive of electricity generator and retailer Genesis Energy

“I don’t believe this ‘tension’ exists in the way it once may have. Our shareholders, whether government, large investors or individual New Zealanders, are increasingly concerned about climate change. They expect action and want to invest in long-term sustainable companies. Genesis has reduced carbon emissions by 50% in the past decade while continuing to provide the back-up electricity relied on by New Zealand electricity retailers.

“We’ve recently announced an agreement with Tilt Renewables which provides the foundation for the 130MW Waverley Wind Farm to be built in South Taranaki, and we’ve launched a partnership with four other large companies to form the Drylandcarbon forestry partnership. We are also improving efficiencies across our power generation business and openly exploring energy technologies that could play a role in New Zealand’s low carbon future.

“In New Zealand we have an opportunity to use our 85% renewable electricity system to help decarbonise heavily emitting sectors through electrification. It is possible to transition without damaging shareholder returns, there just needs to be some good thinking and cross sector coordination to achieve the best overall outcome for New Zealand.”

Steve Jurkovich, chief executive of state-owned Kiwibank

“Based on the expectations of their own organisations, Kiwibank’s shareholders in turn expect us to operate with environmental and social matters in mind.

“New Zealand Post has the ambition to be a leading sustainable business and have put sustainability at the heart of its business. ACC has a strong focus on the safety and wellbeing of New Zealanders. The New Zealand Super Fund is a leader in its approach to climate change strategy and is supporting us as we work through our own strategy development process.

“This year we looked at our emissions profile and have established targets to reduce the areas where we contribute the most to climate change – electricity, travel and our corporate vehicles.

“We also have a real opportunity to support climate change action. Where we can influence is how and where we lend money and support our customers to understand climate change risk in their home or business.”

Rob Everett, chief executive of the Financial Markets Authority (FMA)

“The way financial markets tend to work is in many respects they are very short term and a lot of shareholder focus is on short term profits.

“If you look at what we saw in Australia (the Royal Commission into banking), and the global financial crisis, it was driving short term focus on profits at the expense of the long term viability of business models, but also of communities and customers.

“What we can do at the FMA is try and encourage the sector to focus on the long term sustainability of their business and the long term interests of their customers and resist the temptation to just react to short term demands of the market.

“For example, quarterly reporting drives incredible short-term pressure in businesses to hit the next quarter’s numbers, or to put stuff into the following quarter because you don’t need to report it.

“It drives behaviours that have nothing to do with the long term value of the business or the long term interests of customers. A lot of people would question the benefits of quarterly reporting – I’ve always had issues with it.

“The change I’ve been trying to force debate on is the extent to which we can get boards of listed entities to acknowledge there’s a longer term stewardship role which isn’t just about short term profit, it’s not just about a share price. It’s actually about a broader contribution to society.”