Oil industry insiders and critics are sounding the alarm over the sale of a Taranaki oil well, warning that the buyer is gambling on oil that may not be there – and that taxpayers may be left holding the bag if the bet doesn’t pay off.

Update, 10 June: A response from the Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand (PEPANZ) has been appended to the end of this article.

Last month, the Austrian oil and gas giant OMV announced it would be selling off its 69% share in the Maari oil field, off the Taranaki coast. The NZ Herald report on the sale said OMV was selling up “as part of its strategy to shift its production away from heavier-emitting resources”. But both climate activists and industry insiders say there is something more to the sale. In short: they allege OMV is selling off a useless well to avoid the cleanup costs.

OMV is one of New Zealand’s largest oil companies, and its largest gas producer, controlling the Maui and Pohokura gas fields. OMV sold its share in the Maari oil field to a much smaller company, the Singapore-based Jadestone Energy, for USD$50 million.

That might seem like a lot, but in return for New Zealand’s most productive oil field, which alone accounts for nearly a third of the country’s production, Jadestone got a very good deal. Assuming prices stay around where they are now, at USD$45-$49 a barrel, in theory Jadestone could make back the cost of the sale in less than a year of production.

OMV’s willingness to go ahead with the sale at such a low cost is just one of many reasons that industry insiders are worried. What can account for OMV’s apparent eagerness to get rid of such a lucrative asset?

Old rigs

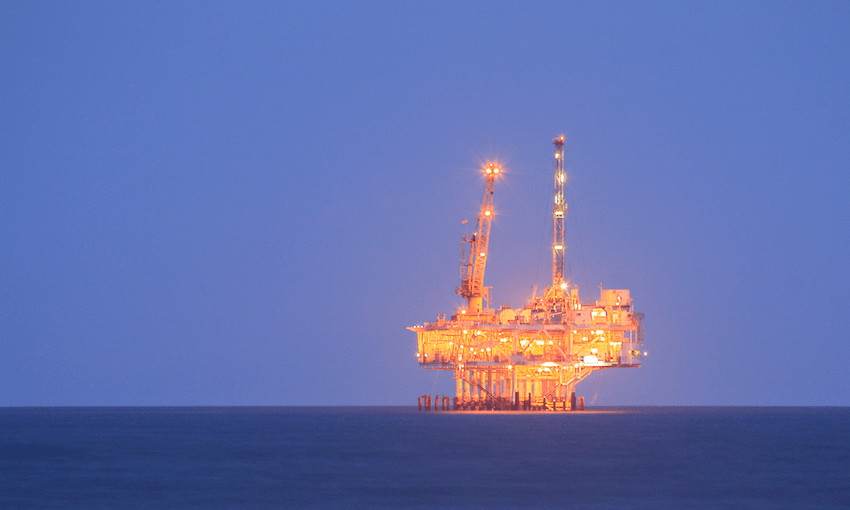

Environmentalist groups allege that the equipment used at the Maari oil field is on its last legs. Both the wellhead platform itself and the floating storage and production vessel (FSPO) have had serious technical problems in the past.

The FSPO vessel Raroa is an ageing Liberian-flagged ship permanently moored next to the wellhead platform. The vessel has had issues with oil leaks in the past, causing two spills in 2010, and another in 2015.

The 250 metre long ship was built in 1980, and has had issues with leaks from its transfer hoses. The wellhead platform itself has also had technical issues. The platform was heralded as a technical marvel when it was first built, as it had to contend with unusually deep water, high waves, and earthquakes.

However doubts about its structural integrity were raised in 2016 when a 1.4 metre long crack developed across its supporting struts, requiring an evacuation. The crack was apparently caused by regular wind and wave action that the platform was built to withstand.

How much oil is down there?

When an oil well is first drilled into the ground, the gases and fluids stored under the ground are often under enormous pressure. Managing pressures is where most of the human input in oil extraction is required, as mismanaged pressure can have disastrous consequences.

The Maari oil field is relatively new compared to many of New Zealand’s other fields, and newer fields tend to be under greater pressure and much more productive. For the first three years of operation after Maari was opened in 2009, the field produced an enormous 5-6 million barrels of oil per year. By 2013, the field began steadily producing a more modest figure of around 2 million barrels, production which has kept steady until today.

At the time of its opening, the field was only ever intended to be productive for 10-15 years. That time limit is soon set to expire.

But the question of how much oil remains has recently become a lot more complicated. Last week it was reported that Jadestone believes there is much, much more oil than OMV has estimated. Jadestone believes that re-pressurisation work done in 2018 has made the field much more productive, and has extended the lifespan beyond the 10-15 years initially reported.

In September, one industry insider anonymously raised concerns over Jadestone’s plans, saying that its projected profits seemed to rely on finding oil that simply wasn’t there, according to official statistics.

That insider seems to have been proven correct: Jadestone estimates a maximum of 13.9 million barrels are yet to be extracted, more than twice OMV’s maximum estimate of 5.7 million, and well above any provable figure.

Even the lower figure might seem like an enormous amount, but the volume of oil is only one side of the story. Oil wells struggle to keep ahead of high operating costs, and most become unprofitable long before all the oil is actually extracted.

To overcome the operating costs Maari is expected to have, as well as the costs of decommissioning the site, Jadestone would need to find more oil than has ever been proven to exist. It’s a gamble, but that’s business as usual for Jadestone.

According to the industry insider, Jadestone’s business model relies on acquiring old wells for dirt cheap prices, then cutting costs down to the bare minimum to squeeze profits out of otherwise unprofitable rigs. Using these methods, Jadestone hopes to be the “last man standing” in a declining oil industry. The company specialises in “infill drilling,” essentially drilling more and more wells in a small area, with the hope of finding additional oil reserves that were missed in the first sweeps.

All the cost cutting in the world won’t help if the oil simply isn’t there. If only the proven reserve – some 3.3 million barrels – can be found, gross sales would barely cover the estimated cost of decommissioning the site: about $200 million.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before

The situation at the Maari oil field is eerily similar to the case of Tamarind Taranaki, a subsidiary of the Malaysian-based Tamarind Resources which acquired the ageing Tui oil field in 2017.

The company had an extremely similar business model to Jadestone, believing it could take an old, relatively unproductive oil field, and gamble to find new pockets of oil. The gamble didn’t pay off, and by December last year the company had gone belly up.

That meant that all of Tamarind’s equipment was left floating 50km off the Taranaki coast for months as government contractors scrambled to decommission the site. The FSPO vessel Umuroa was ordered by the high court to stay at sea, slowly burning through the 40,000 barrels of oil on board, and posing a significant risk of oil spill, according to the vessel’s own operators.

Tamarind ended up owing its creditors $484 million, $155 million of which was owed to the government. The operator of the Umuroa was owed another $150 million, and numerous workers and contractors across Taranaki were never paid their due. Iwi were particularly furious that Tamarind was able to abandon several agreements with local hapu.

Despite the fiasco at the Tui offshore rig, another Tamarind subsidiary still operates onshore rigs across Taranaki. One subsidiary can cost the government millions and go into liquidation, without other subsidiaries or the parent company suffering any consequences.

Jadestone Energy chief executive Paul Blakeley told RNZ comparisons with Tamarind Taranaki are unfair, pointing to Jadestone’s track record in other oil fields and its status as a publicly listed company “subject to the same level of transparency, scrutiny and regulation as all other PLCs”. He said Jadestone had assured the government it had the resources to honour its commitment to decommission and clean up after it had finished drilling at Maari.

Will the sale go ahead?

After the public anger over the Tamarind sale, the government introduced a new rule meaning companies would require permission from the energy minister before selling off any older oil fields.

OMV has good reason to want to make the sale now, as the current energy minister, Megan Woods, has requested that her staff strengthen the existing legislation around oil field decommissioning. This change is expected to come into effect in 2021, and would prevent oil companies from avoiding decommissioning costs through last-minute sales.

OMV has insisted that the sale is taking place for environmental reasons.

The sale “underlines OMV’s strategy to produce significantly more natural gas than oil to reduce the carbon intensity of the product portfolio in the future,” said Johann Pleininger, deputy chairman of OMV’s executive board.

However this magnanimous decision on OMV’s part has put the Maari oil field in the hands of a much smaller company with a reputation for driving down operating expenses no matter the cost. The technical difficulty of the rig, the age of the equipment, and the proven propensity for oil spills are all factors which, activists say, probably shouldn’t be left to the lowest bidder.

The increased risk to the workers on the rig and supporting shipping is also a concern, as pressure to lower operating costs often results in lax maintenance and safety standards. Managing the potential for spills in an area populated by endangered pygmy blue whales and Māui dolphins will be another challenge.

The government has indicated it will be pursuing a tougher environmental policy, with Jacinda Ardern declaring a climate emergency just last week. It remains to be seen whether these tougher words will be backed up by further action against fossil fuel extraction across New Zealand.

The Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand responds:

The sale of this type of asset is very typical and reflects the natural progression of oil and gas assets globally, where tier 1 operators move on, look to reinvest elsewhere and are replaced by smaller, more nimble, operators who able to more efficiently operate and invest in the asset. This cycle occurs across all major oil and gas regions in the world and is more usual than not.

The asset is not unprofitable and Jadestone’s business model does not rely on cutting costs “to the bare minimum”. However, inefficiencies are identified and addressed. Rather than cutting costs Jadestone proposes an investment programme that rejuvenates the asset and also accesses currently undrained oil.

Jadestone has an excellent track record with this business model and has proven credentials with its two operated assets in Western Australia, where mid-life assets have been rejuvenated through an investment program that has resulted in increased production and added reserves.

A good example is their Montara asset in this region where they acquired an asset which was subject to seven enforcement actions under the control of the previous operator and is now operated in a very safe and efficient manner.

Jadestone is a respected operator in Australia – perhaps one of the most strictly regulated jurisdictions globally. They have an excellent record in health, safety and the environment and these results are publicly available.

They are publicly listed on the London stock exchange and have institutional investors who demand excellence in this area. Accounting for liabilities associated with decommissioning form a key component of the ongoing reporting to the London exchange.

Jadestone has offered a number of assurances to the New Zealand Government (as the regulator) in respect of their obligations for decommissioning and continues to work with them to complete the approval process.