A Canterbury startup is exposing medical equipment manufacturers’ deliberate one-use design tricks and proving that hospitals can reuse and recycle.

There has been a lot of hype about the phasing out of plastic bags at supermarkets. But what about far more expensive items which only ever get used once and are then thrown away?

A case-in-point is medical devices in hospitals. We want anything used to diagnose, treat or operate on us to be clean and sanitised, but one-use items worth hundreds of dollars are both a drain on the stretched health care system and bad for the environment.

There is an inherent tension in the medical industry. If profit is your motive then you might not want a $500 one-use device to be cleaned and used again. Wouldn’t you rather sell five devices for $2,500 than one that gets cleaned five times?

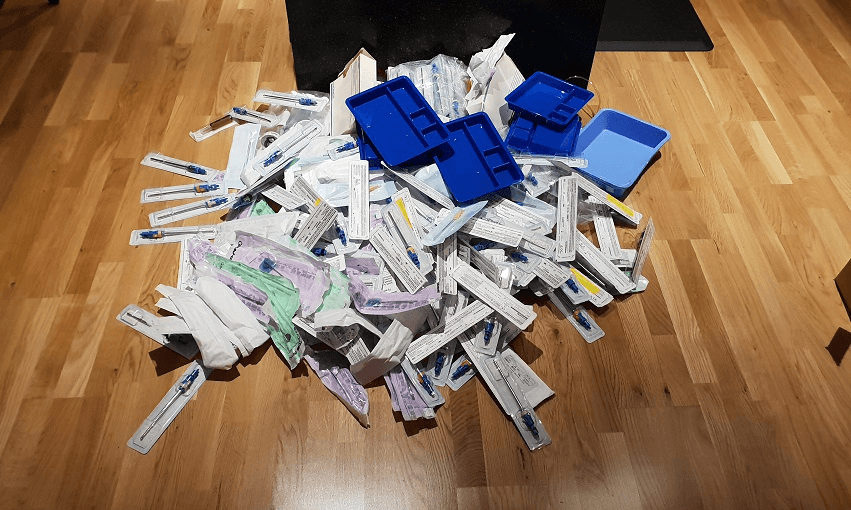

Statistics around usage and trashing of such devices are sparse but anecdotally it is clear that there is huge waste in the system. An expiry date is passed – throw it away. Device says single-use – throw it away.

Oliver Hunt is a University of Canterbury engineering graduate who believes there is plenty of room for hospitals to improve while still keeping to the highest standards of safety. He started his company Medsalv as a way to reduce medical device waste.

Medsalv takes single-use devices from hospitals, cleans them, checks that they still work, and gives them back for a lower price. “We keep doing that until we can’t do it any longer, at which point we break the devices down and recycle, if possible,” Hunt says.

His family background drove his desire to start the venture.

“My family is sort of infested with doctors, not that that’s a bad thing, but my mother’s mother and her father were both GPs, Mum is an endocrinologist, her brother is an orthopaedic surgeon, my auntie is a physiotherapist.”

Hunt was keen on following the family profession, but he was also always in the garage building things. This together with a strong interest in entrepreneurs and a desire to do good led to Medsalv.

The idea to focus on reprocessing devices came from a conversation with his surgeon uncle. “I needed a project for my Masters of Engineering and Management… and we were discussing health care, and my question to him was, ‘what happens if we spend more money on health care?’ And he said, ‘it doesn’t really matter how much we spend on health care, it is the efficiencies in the system’.

“He proceeded to show me all these devices that were out the back of his garage which were single-use, but they were unused because their packaging had expired.”

Hunt’s uncle thought there would be a way of sterilising the devices, but Hunt obviously did not have access to equipment like a $350,000-plus Gamma radiator.

“It kind of started the wheels turning, so I did some research and created a literature review and went from there.”

Hunt got a boost via a last-minute opportunity to join a summer programme run by the University of Canterbury’s Centre for Entrepreneurship. At the end of the programme he won ‘people’s choice’ and ‘best opportunity’ after the pitch sessions in front of experienced business people.

Other pitches, awards and recognition have followed, as well as more research. It became clear that medical devices in the $20 to $1,000 price range were his sweet spot, as cheaper ones weren’t worth recycling. Medsalv’s opportunity was to plug the gap where no cleaning instructions for a device existed.

Hunt believes the spotlight hasn’t been on medical devices before because unlike with other single-use products such as drink bottles or cups there’s little visibility.

“Most people in hospital as a patient don’t see single-use devices because they are under anaesthetics when they are being used… It means that companies can get away with a lot more, and there are well-documented instances of companies driving the ‘single useness’ of their devices by, for example, putting in microchips that will fry catheters once they are used, so they cannot be reprocessed.”

So if you go in for an operation should you be concerned if a device has been re-purposed?

Medsalv has a rigorous process of analysing each device and working out how they can best be cleaned, Hunt says. “An invasive device that is going all the way up into your arteries is clearly treated in a different way to a non-invasive device.

“So you might use a bunch of ultrasonic baths for an invasive catheter, and then you finally sterilise it using a specific type of sterilisation. But for a non-invasive device you can treat it with high level disinfection.

“We fundamentally become the manufacturer, so anything that was to go wrong with the device, that is on us. So we have to take the steps to prevent that from even being possible.”

Medsalv’s future looks bright. It won the inaugural Dream Believe Succeed award in 2018, and has received grants from the Canterbury Joint Waste Committee, Auckland Council, and Sustainable Investment Fund. It is also a finalist in this year’s Westpac Champion Business Awards.

Hunt feels the timing is perfect for the venture. “We have hit it right. People seem to care a lot more about things going to waste, and so they should, because we send a tremendous amount of waste away.”

Medsalv probably fits the criteria of being a social enterprise, a business which exists for more than just profit.

“The social enterprise one is a difficult one,” Hunt says. “If you take it as a business that does good, then we fit the bill quite well because just by operating we directly reduce the number of devices that are sent to landfill and we directly reduce the expenditure on health care from the public and private health care system.”

He’s not convinced Medsalv will adopt the label, however. “Part of it is because we don’t want to confuse people, and the fact that our business model is somewhat unconventional, especially in New Zealand, and we don’t want to confuse people on that. And a lot of people wouldn’t know what a social enterprise necessarily means. If it is clearly understood and has a good framework for it, then it is something we would explore.”

Steven Moe is a Partner at Parry Field Lawyers in Christchurch. This article is based on an interview for his Seeds podcast. The full interview can be heard here.