Opposition to a new online homecare service could be a sign of things to come, as the ageing population pits workers’ employment rights against the right of older people to choose who cares for them.

Wellington homecare worker Jane* once had an elderly man yell at her and order her to leave the house.

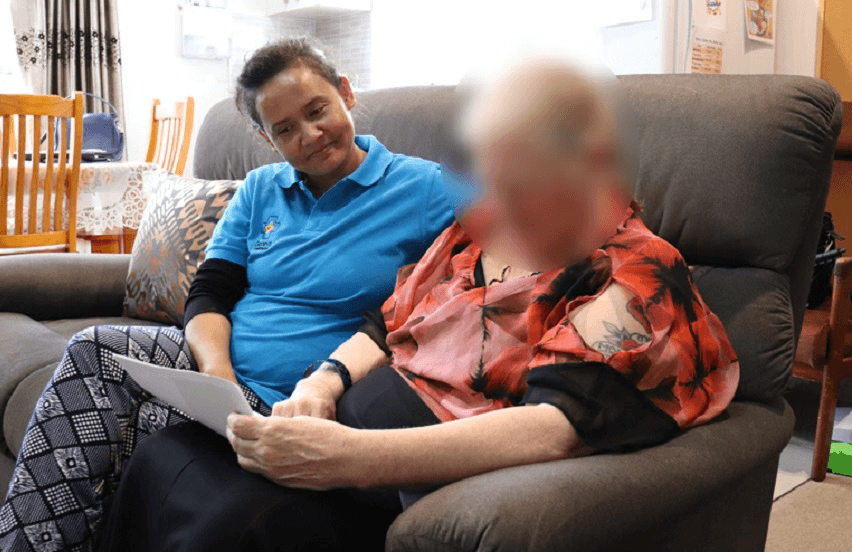

Another client spoke not a word of English. While his wife was able to translate it required two people to look after him, so Jane’s employer Geneva Healthcare had the wife down as the second carer. “But he didn’t want his wife having to do things that we were there to do,” Jane says. “It got quite interesting at times.”

Dealing with crankiness and discrimination is part of the job for the army of support workers providing in-home care for New Zealand’s elderly and disabled. They fear a new online portal allowing clients to pick and choose carers based on personal profiles is the beginning of an era that will enable, if not exacerbate, these inequities.

The ‘Tinder of homecare’ is how some are viewing Geneva Healthcare’s new My Homecare platform, currently being trialled in the Waitemata District Health Board area in Auckland’s west and north.

The homecare workers’ union, E tū, has voiced concerns ranging from privacy to favouritism, and the fact that members are being asked to embrace the new technology using their own devices with no compensation.

The portal is part of Geneva setting itself up to compete for additional private work on top of the government-funded contracts it currently fills, E tu organiser Kirsty McCully says.

While Geneva has now agreed that only minimum information about workers such as their first name, qualifications and language skills will be mandatory on the portal, carers are encouraged to post pictures and personal details about themselves.

How much will workers have to do just to get a job, McCully asks?

“If you’re a client you’re going to pick people who provide more information,” she says. “If you’re not prepared to sell yourself online, even if it’s to a defined group of people, then you may be disadvantaged as time goes on.”

Like many of the caring professions, homecare workers seem to be embroiled in an endless battle for better pay and conditions. An industry-wide agreement on guaranteed hours and travel costs was reached only a couple of years ago, and still they care for our most vulnerable under terms other groups of working Kiwis would consider inadequate.

Payments for transport costs are a current bone of contention. Support workers use their own cars to get to and from clients’ homes, and are paid a flat rate of a little over $4 for their travel time and mileage up to 15kms. If the trip exceeds 15kms they are paid for their time at the minimum wage plus 50 cents a kilometre. Both mileage payments are significantly below the Inland Revenue Department rate of 76 cents a kilometre.

Even Geneva Healthcare’s CEO Veronica Manion agrees it’s unfair, and she’s part of a national funding review group that is looking at this and other issues. Providers such as Geneva were not involved when the current legislation was designed. “We would have really not done it the way it’s been set,” she says.

Geneva is in ongoing discussions with the union about My Homecare and has been able to allay many of its fears about the portal, she feels.

“We’re trying to tackle an industry that’s been really very traditionally run for the last 20 years,” she says.

“The more we automate things the more money we can use on giving back to our staff.”

The number of people over 65 is set to double in the next 20 years. By 2038, 1.3 million New Zealanders will be of retirement age, up from 750,000 today. Industry body the Home and Community Health Association (HCHA) says as the population ages the personal carer workforce will also need to increase significantly, from 35,600 currently to 73,000.

In recent years care of our senior citizens has been reoriented around the home and community, the HCHA says. Instead of older people spending extended – and potentially unnecessary – periods in hospital or moving into a residential care home, the sector has shifted towards supporting people while living in their own homes.

Meanwhile the Ministry of Health’s ‘Future Models of Home and Community Support Service’ programme is focusing the sector’s attention on giving clients more choice and control over how that care is delivered and by whom.

Initiatives such as My Homecare are in line with the trend towards ‘individualised funding’, Manion says.

“Where the sector’s going is that it may be that we’re given a lump sum of funding, and as a provider we need to assess what a client needs in collaboration with them. It’s up to them how they spend it.

“Geneva is trying to keep 20 minutes ahead and be relevant.”

Jane has refused “point blank” to use the job logging app Geneva workers have had available to them for the past two years. “I just told them, ‘if you want me to use your app you provide a phone with data and pre-programmed numbers’. But I’m not using my phone for work things,” she says.

Manion says 18% of Geneva workers are using the app, which prompts them to answer a set of questions at the conclusion of a job and automatically logs their hours and travel. This compares to the paper system many still use, requiring them to fill out timesheets for each job and either deliver or post them to the office.

She concedes the company provides no compensation for device use and it’s something it may have to look at, because ultimately it would like all of its workforce on the app.

While the app and My Homecare are separate systems – aside from workers being able to view the portal on the app – the technology is part of a wider march towards a more data-driven service.

The app enables those in the field to feed back to Geneva in real time about clients who may not see anyone else all day, Manion says. It also means co-ordinators know immediately if a carer hasn’t turned up.

“They can document if a client’s not eating, or had a fall,” she says. “We can potentially prevent hospitalisations.”

Despite the many advantages of going digital, support workers remain concerned that My Homecare gives clients or their next of kin the ability to select carers based on personal preference, as opposed to letting Geneva co-ordinators find the best match.

It will be up to workers whether they want to improve their chances of being picked by posting more personal details and pictures of themselves on the portal, Manion says. “Of course I think the more you promote yourself the more you’re going to be requested by a client.

“It’s the same now, if you accept all sorts of clients… you get lots of work.”

Allocation of carers on the basis of ethnicities and demographics also happens now, it just may not be so obvious to the workforce, she says.

“Clients will say, ‘I don’t want a Pākehā support worker, I want a Tongan support worker, that’s my cultural fit for my family’. Quite often we get ‘I don’t want anyone under 40’.”

Language skills is another factor. “For some of the older clients, we really need someone who can speak their language.

“If we put someone in who’s not the right fit, it generally doesn’t work out,” she says.

And clients can’t just dial up anyone who takes their fancy, Geneva points out. My Homecare requests are moderated to ensure workers with the right skills and availability are allocated to the shift.

The portal also paves the way for clients to choose from a menu of services, and to book additional services that aren’t funded by the state.

Age Concern chief executive Stephanie Clare prefers to view My Homecare as tool allowing people to actively choose their carers, as opposed to enabling discrimination. And surely competition provides more opportunity, she remarks.

“If you’re a client under the current system you don’t have real say in who looks after you, who comes to give you a shower.

“It might be that you actually want someone that looks and feels familiar to you. When you’ve got intimate care going on, having the trust of someone who does that for you, is that not the flip side of the coin?”

There are other similar portals out there but these are offered by private providers, whereas Geneva is the first provider of publicly-funded services to roll it out, E tu’s Kirsty McCully says.

“A lot of providers in the space are setting themselves up to offer top-up arrangements, services that aren’t covered by the government,” she says.

Along with privacy and safety concerns about workers’ personal information being available online, the union fears it’s the beginning of an erosion of hard-fought for guaranteed hours, McCully says.

“We know what tends to happen in the sector once providers decide to do something…, they have ways of making it difficult for support workers to exist if they’re not prepared to follow that path.”

*Name has been changed