What the B Corp certification actually means and why it matters.

Five decades ago, economist Milton Friedman was concerned about business accepting a social responsibility. In an oft-cited 1970 essay for The New York Times Magazine, Friedman argued that while CEOs could feel an individual responsibility to society around them, “a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible.”

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”

Friedman’s doctrine – that profit trumps all – went on to be taught at business schools all around the world. It was soon the expectation for corporate responsibility (or lack thereof).

What shareholder primacy enabled was a dramatic inflation of CEO compensation. In order to motivate money moves, executives were offered pay based off the company’s stock price. The higher the stock price, the higher the bonus for the CEO. In the US, CEOs went from making approximately 40 times the annual salary of their workers in the early 1970s to a reported 278 times the average pay of their employees in 2018.

While incentivising the CEO helped bring the stock price up, and the stock price going up helped the shareholders and therefore the CEO, there have been some crucial missing elements in the application of Friedman’s doctrine. What’s missing are the employees, the people, their families, and the world they live in.

In August 2019, the Business Roundtable, made up of CEOs from major US companies, released a statement signed by nearly 200 members. The statement outlined a move away from shareholder primacy.

“While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” the statement read. “Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.”

The short statement included a commitment to invest in employees, support the communities in which companies operate, and embrace sustainable practices in business. This may go on to represent a crucial turning point in corporate behaviour. But for many business owners around the world, social responsibility is nothing new.

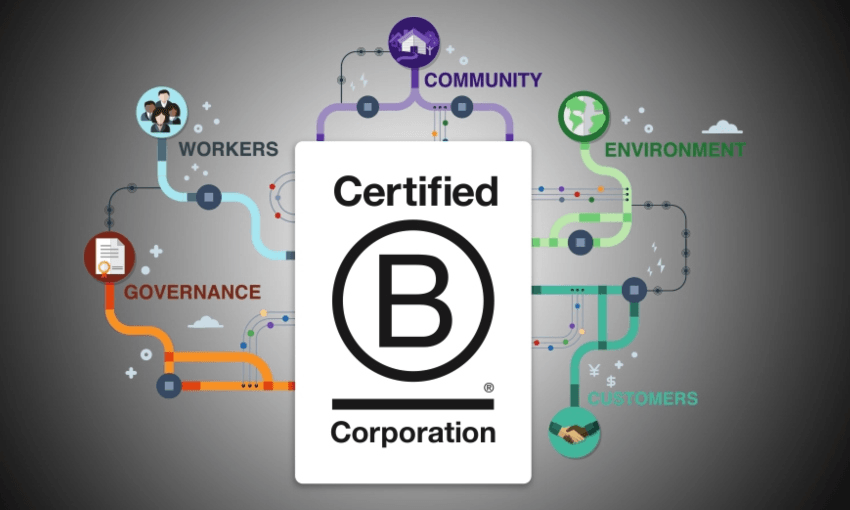

Since 2006, companies across the US and around the world that wanted to make a real commitment to positive social and environmental impact have applied to become registered B Corporations. A B Corp certification requires more than the occasional donation of some profits to charity to qualify. Businesses must prove they have an ingrained commitment to social, environmental, and worker welfare, and they must prove it over time.

Three friends had abandoned their careers in business and private equity in order to create an organisation to solidify the missions of positive-impact companies. In 2007, 82 B Corps were certified, the first of thousands to come.

“Lots of certification schemes are more about ticking certain boxes,” says Julia Jackson, Kiwibank sustainability lead. “A coal mining company with offices that have a recycling scheme and use double-sided printing could still tick a lot of boxes.”

B-Lab, the entity that audits applicants and grants certification, began operating in the US first where some big brands got on board early. A commitment to workers, the community, and the environment is not just signed with an intent to implement – in the US, a B Corp certification is legally binding.

Clothing and outdoor brand Patagonia, famous for its alternative approach to business, has been a B Corp since 2012. When Patagonia received an extra $10m in profit thanks to a 2017 tax cut, they immediately invested it in grassroots activist organisations working to help the environment.

In New Zealand, only about 50 businesses have B Corp certification. And while it isn’t legally binding here, it’s certification is still an arduous and engaged process because it requires consistency across all areas and a true commitment, says Jackson. “Lots of certifications are specific to one area but B Corp is across everywhere. You can’t be great at one thing and terrible at another.”

In February 2018, Banqer, a financial education programme used in schools, became New Zealand’s 14th B Corp. Through its partnership with Kiwibank, Banqer is available free to primary and intermediate classrooms across New Zealand, giving 80,000 kids access to greater financial literacy.

CEO Kendall Flutey had been hearing about the benefits of B Corp for a while before she decided to undertake the assessment. She figured even if Banqer didn’t pass the standards it would be a beneficial experience to audit her company’s ethics.

“One, it really aligned with what we were about as an organisation,” she says. “And two, it gave us an opportunity, even if we didn’t qualify for registration, to at least know where we stand. Their due diligence process is really thorough so I don’t think we would have been put through that process in such a structured way had we tried to go about measuring our impact broadly by ourselves.”

The B Corp assessment is intensive, with self-completed questions and prompts as well as an audit. To qualify as a B Corp, businesses must have an explicit social or environmental mission. Being good at recycling or printing double-sided won’t cut it. It took Flutey six months to complete the process for Banqer. During that time, she learned where her small company of six employees was falling short, because “you don’t know what you don’t know.”

“Our weakest area was the environmental side of things,” she says. “We’re pretty strong on people and governance and we’ve got a pretty strong social impact given what we do, but environmentally we were in a co-working space and a lot of things were out of our control. We were planning on moving out of the co-working space soon anyway but it prompted us [as] there was another reason and some other benefit.”

Businesses moving towards socially responsible values and practices has been a slow burn. First came organic: consumers were willing to pay a steeper price for products manufactured without chemicals. Then came ethical: quality assurance that goods were produced in fair conditions. And most recently, environmental: cardboard and biodegradable packaging are now a selling point for businesses in plastic-heavy industries. But it’s becoming increasingly difficult for businesses to garner goodwill simply for not destroying the planet or not exploiting its workers.

The B Corp community represents businesses that accept a responsibility to not just avoid making things worse for others but to improve the lives and environments of everyone impacted by their business. For many, particularly younger consumers, it may seem like a given for corporations to help communities. That’s why Flutey is confident that the B Corp certification numbers will only grow.

“It will become normalised, I have utter confidence in that. I work a lot with students and the way they’re drawn to social issues, even if the core of their business isn’t socially minded, the way they think and how they want to do business is different. Whether the incumbents and big businesses get on early or it takes the next wave of young leaders… one way or another I do think it’s going to happen.”

Flutey believes, or at least hopes, that in future a B Corp certification will prove near redundant as it will sit alongside government regulations.

Earlier this year Kathmandu became the largest local company with the certification. Otherwise it’s mostly small businesses like Banqer that have committed to establishing social and environmentally responsible practices. It may feel at times like throwing water balloons at a forest fire, but “New Zealand is a country of small businesses so on aggregate that can have an impact.” Flutey knows that it would be a much bigger task for legacy corporations to change their practices, and is always heartened when she sees medium and large corporations receiving the B Corp badge.

“I don’t think you can just throw money at B Corp. You have to throw money and time and decisions and changing of policies, and most of all you have to throw commitment at it,” she says. “It just has to be genuine. Whatever shape or size your business is it just has to be genuine commitment.”

This content was created in paid partnership with Kiwibank. Learn more about our partnerships here.