New Zealand’s film industry has always been about location, location, location, but what about everything else? What about all the stuff that comes after filming? Jihee Junn talks to Department of Post’s Katie Hinsen at the company’s new state-of-the-art headquarters about her mission to make Auckland into a post-production powerhouse.

For much of late 2016, tough guy caricature Jason Statham was practically calling New Zealand home. He was spotted in Piha, he was spotted in Grey Lynn, he was often spotted at Westmere cafe Catroux grabbing a mochaccino or something. But for the most part, he was spending his days in Kumeu shooting scenes for The Meg – Hollywood’s answer to getting Jason Bloody Statham to punch a whopper of a giant prehistoric shark. It was Kumeu Film Studios’ inaugural project, built in the hopes of luring more big shot productions to our backyard which, by all means, seems to have worked – Disney’s live-action remake of Mulan started filming at the new West Auckland studios earlier this year.

Not since the heyday of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien trilogy has the local screen industry found itself busier. Government grants have done a lot to help to bring blockbuster films like The Hobbit (controversially) and James Cameron’s Avatar sequels (all four of them, yikes) to our tiny, mostly Wellington-based shores. But it turns out it’s not actually Hollywood that’s causing the nationwide backlog – streaming services like Netflix and Amazon are helping to keep studios such as South Pacific (home to Amazon’s upcoming US TV series The Wilds) and Auckland Film Studios (currently filming Netflix’s adaptation of The Letter For The King) booked up right into the new year.

The benefits of having international productions filming in New Zealand are obvious: it’s good for tourism, it’s good for employment and – broadly speaking – it’s good for the economy, helping to feed an industry that contributes over $1 billion to real GDP. But as local film studios in both city centres take advantage of the flood of work arriving internationally, it’s a slightly different story for those working at the more technical end of the industry spectrum.

“Post-production is a high-tech industry where innovation is a key driver of success,” the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research described in its report on the screen industry late last year. “The international market for post-production digital effects is globally competitive and the highly skilled creative labour force is globally mobile.” In fact, it’s why most studios like Disney take their work back to North America once filming here wraps up. It happened with The Chronicles of Narnia, it happened with A Wrinkle in Time, and with the upcoming remake of Mulan, it’s going to happen all over again.

The situation is particularly stark in Auckland: although 70% of New Zealand’s filmmakers and crew base themselves in the country’s most populous city, the lack of high-end resources has forced almost 80% of post-production work to go to Wellington where Peter Jackson-owned companies Weta Digital and Park Road Post dominate. For Netflix and Amazon work, local productions are often forced to do their finishing work overseas because there are no facilities available in the country that are up to streaming service standards. For example, in order to be able to do work for Netflix, you have to be audited and accredited as a Netflix Preferred Vendor, or NPV.

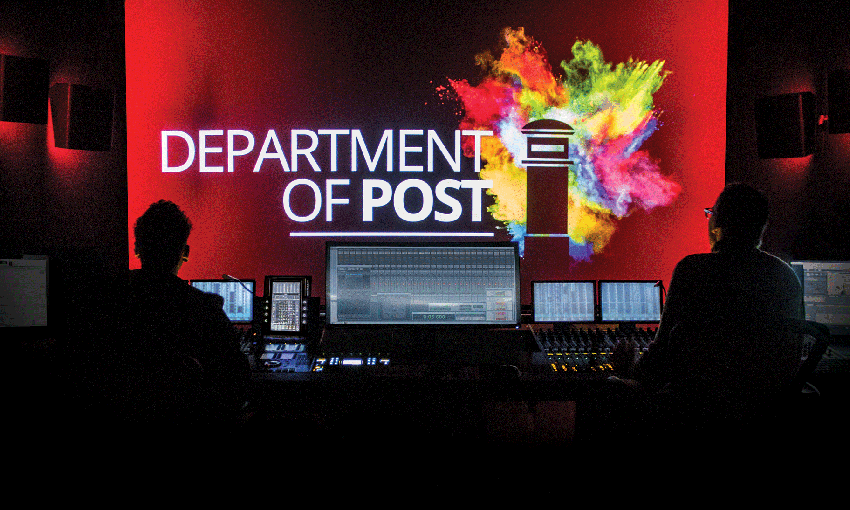

“[That’s where] the new facility comes in,” says Katie Hinsen, head of operations at post-production company Department of Post. We’re meeting in a large room at DOP’s freshly built headquarters on Newton Road which, in recent months, has been accredited as a gold status NPV, allowing it to work on shows such as David Farrier’s Netflix original Dark Tourist.

“My vision over the next five years is I want local productions to extend their spend in Auckland by 30% of their budget and international productions by 10%. It’s not a lot, but it’s still significant. A lot of the time, [overseas productions] will come just for the location, but we’re more than just a pretty face here in New Zealand, you know.”

As the faint hum of nearby construction patters away in the distance, Hinsen takes me on a quick tour through DOP’s labyrinthine new three-storey complex. On the ground floor, there are rooms to do colour grading, sound design and visual effects which are kitted out with the latest in HDR tech. There are edit suites that get hired out for months on end that lets you have an editor and director in one room and an assistant tapping away in another. There are even audio booths that are practically ‘floating’ as rubber contraptions soak up every little vibration and sound like a damp wool cloth. Upstairs, two cinema-size theatres – one for screening/colour grading, one for sound mixing – remain unfinished as they wait for seats, screens and projectors to arrive from Italy and France. But once it’s done in the next few months, possibly weeks, Hinsen and co will have a lot to boast about: it’ll be the most state-of-the-art post-production facility in the whole of the Southern Hemisphere.

“I want international work to come here, but I also want to keep it here,” Hinsen tells me. “With Kumeu opening up, Auckland Council and the Film Commission have already been doing a lot of work to bring people here, but I don’t think they’re doing enough to make them stay here a bit longer and use some of our post-production talent.”

“For example, The Wilds are renting out space and using some shooting crew [locally], but it’s not a Kiwi production. So once they’re done with the shoot they’ll just pack up and leave. [Editor’s note: Following publication, it’s been understood that Auckland company Cause & FX has picked up visual effects work for The Wilds]. That’s the way it’s been for a long time and it’s been really common. The promotion of New Zealand has always been about location, so a lot of productions come here just for that. Sometimes they bring their own staff as well – A Wrinkle in Time even brought their own personal assistants!”

“That was why this place had to be the most state-of-the-art facility in the region and the world,” says Hinsen. “It had to be in order to make people think that New Zealand was good enough to do this work.”

Despite spending more than a year stuck in construction limbo, it certainly hasn’t stopped the company from helping to finish some of the year’s most memorable works: Waru, The Breaker Upperers, Dark Tourist and All or Nothing, the latter being Amazon Prime’s All Blacks documentary which also happened to be New Zealand’s first ever show released in HDR.

This year, it was estimated that Netflix would be spending anywhere between $12 to $13 billion commissioning content for its giant catalogue of entertainment. Of that amount, 85% of new spending was earmarked for original series and movies, and with more than 80 million subscribers worldwide, Netflix is increasingly making the effort to commission more new, unique, hyper-local stories that speak to a specific global audience – one that includes Aotearoa.

“Netflix don’t want American stuff made by New Zealanders. They want New Zealand stuff made by New Zealanders. Think of Taika Waititi, think of David Farrier – people love New Zealand right now! But to be able to get more of that money coming into the country, we need to be able to provide extended services.”

“That’s why I’m working so closely with the likes of ATEED (Auckland Tourism, Events and Economic Development), to show them that film production isn’t just about shooting and location – there’s all this other stuff that can help bring money into Auckland as well.”

Before joining the company back in April last year, Hinsen was working in the US as a colourist in LA and New York City. But with two decades worth of post-production work under her belt and a desire to return to New Zealand (“I was ready to leave America because it was fucked”), she was prepared to try something a little different. In 2016, she started talking to DOP co-founder James Gardner (who she’d met via “nerd circles” several years prior) about her idea – a business case, actually – of making Auckland into the post-production powerhouse she knew it could be.

“They (Gardner and co-founder James Brookes) wanted to expand anyway as they’d started to outgrow their facility on Maidstone Street,” recalls Hinsen. “I had this big idea [of building a state-of-the-art post-production facility in Auckland], so I was like, ‘Let me help you do that. Let me help you expand’.”

While orchestrating a company’s most ambitious expansion plans to date might seem like an unfamiliar task to someone who’s worked in post-production for more than 20 years, it’s clear that what Hinsen lacks in formal business training she makes up for with ambition and smarts that could rival any modern high-power CEO. Besides, she’s also the co-founder of Blue Collar Post Collective (BCPC), a global grassroots non-profit supporting emerging talent in the post-production industry.

“I don’t fuck around. I’m known for that. I really don’t do anything by halves,” she tells me, hardly missing a beat. “I’m ridiculously, stupidly ambitious and I love the fact that people underestimate me. People thought we’d be putting in a few more edit rooms and do some more reality TV. We were getting a bit of tall poppy syndrome [from the rest of the industry] and I got that whole ‘Who do you think you are? You’re not in America anymore.’

“People definitely underestimated this company and that was awesome because that’s exactly what we needed. Everyone here contributed to building this facility, spending time on our hands and knees cabling and carpeting. It was as DIY as it possibly could be.”

It’s hard to say how many people really work at Department of Post. With just a handful of people employed as core staff and the rest brought on as freelancers on a case-by-case basis, Hinsen says it’s a new model the company is trying out.

“Normally, you have all the artists on staff. Producers then decide who they want to work with and that’s how they decide where to go [for post-production]. But with the trend towards the gig economy, I don’t think that’s a sustainable model [anymore]. This new model means having a core staff but also maintaining good relationships with freelancers in order to have them on offer.” This would allow producers to pick their own talent and their own facilities. The two would no longer necessarily be tied together, hence making it more of an “a la carte deal”.

The other reason is simply that New Zealand doesn’t have the same level of experienced talent. An ‘a la carte’ deal would allow production companies to bring whoever they wanted from overseas and use more mid-level post-production staff locally to support them.

“If you’re anything like me, you went to Park Road, you did the Peter Jackson stuff and then you went overseas, because what else is there, right? Because there isn’t that level of world-class talent, we can either import them or we can train them, and I’d much rather train them.”

“But say there’s a big international level feature. The production company could bring in a lead recording mixer or lead colourist [from overseas], but they still need three or four other people to work with them, which we can provide. If they want someone from that next tier, they can bring them, but we have an entire support staff in that department.”

Before the end of the year, the company will host an official launch party for its brand new headquarters. Despite being a completely privately funded venture, there’ll be plenty of Very Important People from the public sector attending the event: officials from the Film Commission, officials from ATEED, and officials from the government in the form of Jacinda Ardern who, in addition to being the prime minister, also happens to be the country’s minister for arts.

In 2017, film production revenue increased 15% and, according to Stats NZ, was led by an Auckland film sector that brought in an estimated $489 million. Wellington, however, continues to be the epicentre of the country’s screen industry, particularly when it comes to big feature films spearheaded by Peter Jackson. Mortal Engines, which is debuting at the end of this month at a glitzy premiere in London, was not only filmed in Wellington but finished in Wellington (Park Road Post, of course) as well.

It’s clear that Auckland’s increased involvement has the potential to elevate us into a world-class player. The economic case for it’s there and the business case for it’s there. We’re more than just a pretty face. We’re more than just a Hollywood backdrop. If ATEED really wants to make Auckland a world-class hub for innovation, forget AR/VR garages – the screen industry might be a good place to start.