A mindset from the world of business may have spread out into culture and political life, steamrolling ideas of objective truth along the way, argues Campbell Jones

There has been widespread discussion over the past month about the disappearance of truth in New Zealand politics.

In an important opinion piece, TVNZ reporter Andrea Vance argued that we have entered a “post-truth” era of politics and Colin Peacock at Mediawatch documented this phenomenon across a range of sources.

The fear of truth in politics has a long history. The ancient Greek philosophers dismissively described as “sophists” those politicians and teachers who bought and sold rhetoric and persuasion rather than truth.

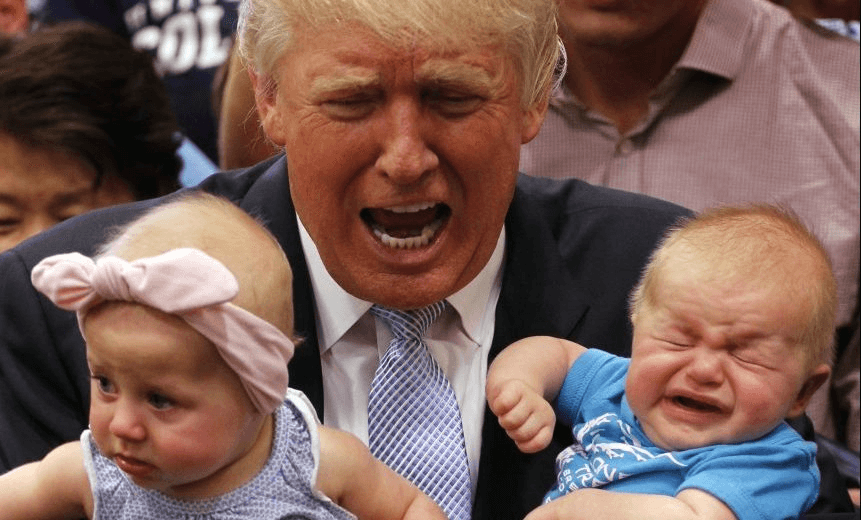

As in the past, the sophists of 2016 say one thing today and another, contradictory thing tomorrow. Most importantly, though, they don’t experience any particular discomfort or embarrassment in this contradiction. They have no genuine interest in truth, which is for them an unhelpful distraction from achieving their ends.

The critique of sophistry is one of the founding gestures of philosophy. More recently, political philosophers have shed considerable light on the changing relationship to truth in politics.

Of particular interest has been the widespread rise of various forms of “post-political” politics since the 1990s, in which politics is emptied of content and of claims to truth.

In my own research on the place of truth in politics, I have been interested in the question of why truth has been so degraded in recent years. I’ve found that it is only possible to answer this question by looking carefully at the social, economic and ideological environment in which the opposition to or avoidance of truth has developed.

This environment has been framed to a significant extent by the way ideas from the practical world of business have spread out into culture and political life. Of all of the ideas that impact on life today, central are those from the world of finance.

While there has been a thorough “financialisation” of the economy, which can be seen in the vagaries of the real estate and financial markets, finance has also brought with it a set of ideas about investment, risk management, hedging and the like.

These, in turn, have had an important impact on contemporary culture and politics. It is not by coincidence that we are all told today to think of our choices as “investments” in ourselves with the prospect of possible future returns.

This rise of finance across the whole of life is a crucial key with which to unlock the mystery of what happens to truth in culture and politics today. In short, finance and a financialised consciousness face a very real opponent in truth.

Truth is a problem for a financial mindset because it pays no dividends. Truth is also inherently unsettling and risky – it overthrows previous things that were thought to be true. Truth, moreover, is something that applies equally to all of us.

The rejection of truth in politics is not coincidental but the result of a particular set of political and ideological priorities. In fact, I believe truth is one of the central opponents of the model of the economy and the politics of the current prime minister of New Zealand.

In its absence, there is only particularism and individuals with their values, beliefs and interests. Economic theory and finance pride themselves on being radically “subjective” in that they only see the particular and always different interests and preferences of individuals.

By contrast, truth is one of the words that we still use to register those things that, despite and beyond our particularities, bind individual mortal human beings together.

This is why the idea of truth and of the individual in finance and in the politics exemplified by John Key is in profound contradiction to the most ancient wisdom of this country and with the socialist and social democratic politics that marked its more recent past.

It is also against this concept of the individual and the disavowal of truth that we can see the rise of a new politics of the left that I believe is about to break into the open in New Zealand.

This politics is not grounded in particularism but in the universal right of access to air, water, housing, healthcare, education, culture, political organisation and sovereignty.

Insofar as it equally hesitates to articulate a politics of truth, the present parliamentary left in this country fails to rise to such demands, grasping as it does at damage control and the politics of competitive individual aspiration.

The international experience of recent years, and of our immediate present, might serve to remind us that truth and ideas of universal rights of access are not dead, but are in the course of being reborn.

Campbell Jones is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Auckland