Sam Brooks reviews the most anticipated game of 2019: Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding.

A man walks, with dogged purpose, across an empty but beautiful landscape. Every few seconds, a blue wave radiates outwards from him, highlighting little things dotted across that landscape – a ladder here, a rope there. A stack of cargo boxes balances precariously on his back. Every now and then, a username appears next to a metal structure, asking to be liked. Low, moody music occasionally plays. There is no talking.

This describes most of the gameplay of Death Stranding, the new game from madman/mastermind Hideo Kojima and the first after his split from Konami. It’s one of the most anticipated games of the year and the one most shrouded in mystery. What is Norman Reedus doing on that beach, and why is he naked? Is this a secret Metal Gear Solid game? Is it a walking simulator?

You can’t talk about Death Stranding without talking about Hideo Kojima, at length. His handprint is all over the thing, as it is over any game he puts his name on. The director gained fame and notoriety with the Metal Gear Solid series, making him perhaps the only game creator who is talked about as much as the games he makes. His penchant for unsubtle political commentary, even less subtle characters (remember Hot Coldman?), and a dedication to both gleaming eye seriousness and wild camp has won him devoted fans and cursed him with vocal detractors.

The first two Metal Gear Solid games turned Kojima into both unimpeachable legend and enfant terribles – the first game simultaneously defining the stealth genre and bringing gaming ever closer to cinema, while the second ended up being a creator temper tantrum turned thesis on meme theory. It’s a legacy that’s wobbled a bit since, with much derision being thrown at Metal Gear Solid 4 for its overlong cut scenes, and also at Metal Gear Solid 5 for… well, pretty much the same thing. But also for being an incomprehensibly plotted game.

Where you sit with Kojima and his style of storytelling determines, obviously, where you sit with any of his games. For transparency’s sake, I’m a reserved fan. I respect and admire the invention and depth of his games – there’s almost no question that the Metal Gear Solid games are some of the most cared and loved-for blockbuster games over the past two decades – while being solidly ambivalent on his talent as a storyteller. I’m all for excess in art, and while I solidly stand behind Metal Gear Solid 4 – one of the biggest trolls in gaming history – there’s no question that his ambition often exceeds what he’s able to do. He wields basic writing tools like dialogue, subtext and symbolism like blunt clubs. He hits the general spot, but when he’s dealing with subjects like nuclear disarmament or the colonial terrorism of language, some more surgical precision helps. It’s as though he knows what picture he’s painting but not how to draw the people in the painting.

With that said, there’s no doubt that Kojima the storyteller can often hit true. While people claim Metal Gear Solid is a peak that Kojima’s never been able to scale again, I’d argue that Metal Gear Solid 3 is actual Peak Kojima™. A simultaneous parody and loving tribute to a 60s spy film, it ended up being both a tremendously silly (remember the guy who shot bees at you?) and deeply engrossing video game with more wrenching moments than you’d expect. I don’t think I’ve seen a relationship in video games more complex and more complicated than that between The Boss and Naked Snake; full of tragic unrequited paternal-slash-romantic love, cut short by the very system that made that love possible. He’s like the James Cameron of gaming – it can be easy to make fun of his work in the afterglow, but when you’re in it, you can’t look away, and through some synergy of talent and nerve, you’re moved by it.

So, Death Stranding. Since the game was announced three years ago, with a frustratingly obtuse launch trailer featuring Norman Reedus standing naked among a pod of beached whales, it’s been the source of much consternation and anticipation from the gaming public, as well as a few conspiracy theories. Each trailer seemed to inspire more questions than give actual answers. What’s up with the baby? Will there be peeing? Why is that guy named Die-Hardman?.

But the main question ended up being: what does a Hideo Kojima game look like when he doesn’t have the increasingly tight reins of Konami pulling back on him? The Metal Gear Solid 5 production process was infamously dogged, and it ended up with a game that had an entire chapter cut out of it, and Kojima’s name being plastered over every single mission. Kojima – once the million-selling golden child – was now the moody adult who hadn’t moved out of the basement, while Konami were the disgruntled parents footing the bill. Kojima left the company and his next project with them (a Silent Hill collaboration with Guillermo del Toro) was unceremoniously cancelled. He was a free man once more.

Death Stranding, perhaps more than any other Kojima game to date, gives us two artists struggling with each other, like Jacob and the angel: Hideo Kojima the writer and Hideo Kojima the game director.

Firstly, Kojima the writer (and it’s worth noting that here he works with co-writers Shuyo Murata and Kenji Yano). I can confirm that Death Stranding is as weird as the trailers have made it seem, and I’ll go one step further and say that Death Stranding is the strangest, most obtuse mainstream game that I’ve ever played. It’s set in a post-apocalyptic society (the one trend that this game adheres to, disappointingly) where humanity, or at least America, have isolated themselves in bunkers and cities after monsters have appeared across the land. You play as Sam Bridges (a muted Norman Reedus, sometimes clothed) who is tasked with reconnecting these bunkers and helping to reform the United Cities of America. Things start weird and get weirder. Is it a parable about America? Yes. Is it about how important it is for people to be connected to each other, both literally and emotionally? Yes. Is it a 50-hour long exploration of a deep, existential depression? Maybe!

There’s no point talking any further about plot specifics here, especially because Death Stranding goes to pains to keep you away from those plot specifics. For Kojima (a legendary overexplainer) this works. He keeps swathes of the game’s setting and history from the player, making them feel as unmoored as Sam is. It is, at its core, a game about the human need for connection, and what happens when those connections are severed. The specifics – a whole lot of nouns and liberal use of the word ‘strand’ – are just window-dressing.

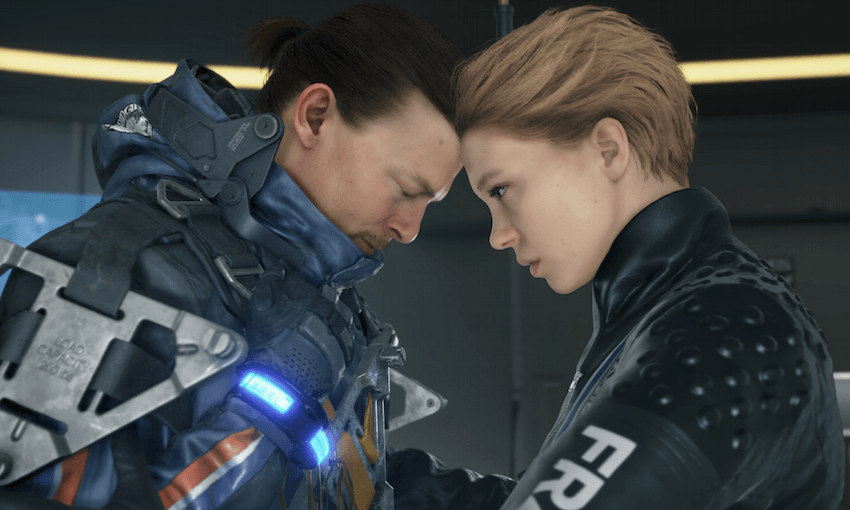

I have to report, sadly, that Kojima has no more control over his writer’s toolbox than he’s had previously – there’s a lot of explanation of minutiae that distracts from what the game is about, and characters feel more defined by their design than what they say. Again, the comparison to Cameron here holds water. He more often than not stumbles into some breathtaking moments solely by getting all the right things together, and he’s assembled an impressive enough cast of people (Mads Mikkelsen, Lea Seydoux, Margaret Qualley, and Emily O’Brien in a particularly strong voiceover performance) who can act their way out of the jargon-built box that they’ve been written into. A late-breaking moment revolving around the line “You love her. You love her, right?” actually tugged at a heartstring, and god knows it was not because of the writing, but because of everything Kojima has assembled around it.

That’s because Death Stranding is, as you’d expect from a game with this much money put into it, a gorgeous looking and sounding piece of work. The soundtrack, a mixture of Ludvig Forssell’s mournful, moody compositions and licensed music from the likes of Low Roar, is deployed effectively without ever drawing focus. It is also, quite obviously, a beautiful looking game, with an aesthetic that does more to underline the emotional desolation of the world than the physical desolation. Everything looks just a little bit off – from the endlessly repeating bunkers to the sudden changes in environment – that you can imagine it as our world even while it feels totally alien.

Which brings us to Hideo Kojima the game director. Death Stranding continues Kojima’s lean away from the tightly controlled and constructed level design of the Metal Gear Solid games and leans into the open-world trend that has infected more or less every genre now. Rather than emphasizing the scale of the world – the entirety of America is condensed to roughly twenty-to-thirty kilometres across – Kojima actually leans into the empty desolation of this post-apocalyptic world and builds on it. The game is constantly, heavy-handedly, reminding us of how lonely everybody is and the need for connection in the text, but it’s the true desolation of the world that really hammers it home. You, as Sam, are alone in this world, and it’s your job to slowly, strand-by-strand, put it back together.

The rest of the game builds on the intricate level of customisation that Kojima played around MGS5. When Sam ventures out from each base, there’s a choice you have to make. How much do you carry with you? Will you need ladders, or will you need weapons? How many grenades filled your own piss will you need? The combat is scarce but robust. You fight only when you need to, and when you do, it’s as stressful as combat in a video game could possibly be.

It’s the most publicized and mysterious aspect of the gameplay so far that is also the best part, and the one that ends up underlining the game’s themes the most, the ‘social strand’ aspect. When you’re connected to the internet, things that other players have left behind will show up in your world – a ladder, a rope, even parts of their cargo. Using someone else’s ladder makes the game easier – you’ll be able to climb this hill or cross this river rather than having to find a way around or stumbling through the damp slowly. When you use one of these things, or even just see them on the overworld, you can hit the middle button repeatedly to ‘like’ it. Conversely, you can place your own ladder or climbing rope for someone to use in the future, and other people can hammer their own middle button to like it.

These likes sit at the core of everything in the game, mechanically and thematically. They work like experience points – the more likes you get, the better of a porter Sam becomes – and they’re delightfully unintrusive. It’s simple and satisfying to like something, and god knows there’s something therapeutic about hammering a button and knowing some stranger on the other side of the world is getting something out of it.

The importance of human connection is not revolutionary theme – it’s basically a riff on ‘only connect’ in Howards End – but damn if this gameplay doesn’t underline and understate it beautifully. Some of the most thrilling moments in this game are when you’ve been struggling for half an hour having overstacked Sam with cargo, and rather than having to walk another five minutes or so around a mountain, you see that some player has left you a climbing rope to scale up a mountain. It’s a reminder that you’re not alone in this gaming world, and the fact that you can not only act on it but reward someone just for being there is a beautiful, elegant thing.

And it’s here where the struggle between the writer Kojima and the director Kojima becomes most clear. Without a single word being said, Kojima emphasizes the importance of human connection. It permeates every second of the gameplay – whether it’s the terror of being ambushed by a BT (a ghost-type thing) or you’re running out of battery as you scale up a mountain – you’re reminded that Sam is alone in this world, and your quest is to make sure that nobody is as lonely as Sam currently is.

It’s when that theme has to be shoved into a 50 hour shaped keyhole that it stumbles, inevitably. It never entirely falls down, despite some pacing issues around the middle half and a third act that is about as stuffed as you can possibly get, Kojima keeps enough held back that you’re always asking the right questions at the right time. But too often, the game falls back on a lengthy cutscene to explain something or emphasize a point, and it feels like someone showing you their working rather than the equation. He’s got the big things down – the theme, the emotions – but when it comes to the actual building blocks of writing, he’s not yet close to mastering them.

Or maybe he just doesn’t care about them. There’s a manic film school student energy to Death Stranding that’s more compelling than good writing is, to be honest. This is felt more in Kojima the writer more than you do Kojima the game director. Kojima’s always been allowed to experiment and break boundaries as a director, and this feels like a logical step on from Metal Gear Solid 5. He is uncompromised here, for better or worse, and allowed to do whatever he wants. There’s a commitment to weird, offbeat humour that is welcome here – a humour that was sorely missing from the dour-as-actual-war MGS5 – and the long, serpentine explanations of motivation later on in the game are classic Kojima.

But where this is most nakedly obvious is with the casting. Kojima’s friends Guillermo Del Toro and Nicholas Windig Refn make the most notable appearances. The director has talked enthusiastically about how much he loved Bionic Woman’s Lindsay Wagner as a child, which is why the actress appears here as her current self, but also as her young, Bionic Woman-aged self. Is there anything more indulgent than that? No. Does it matter here? Not really. In a generation where games are cancelled for being too much, or have features cut or repackaged into DLC, it’s a rare achievement to see a game of this scale with a vision that is 100% uncompromised. It might be a better game if it was a bit more compromised, but I’d rather have this wild artistic statement than a safer, easier game.

I’ve thought a lot about Death Stranding since I finished it earlier this week and not necessarily because of the themes (although I wander between thinking this game is either significantly more profound than I’m giving it credit for or much, much dumber than that). It’s not the plot specifics of the game I remember – my notes look like the ramblings of a mad man, and I imagine they’re not far from Kojima’s own notes on the game – but the actual feeling of playing it. It’s the feeling of pressing like for ten seconds while climbing a rope to make a delivery. It’s the feeling of getting a notification from someone using a ladder I laid down 20 hours ago and is starting their own journey. It’s the feeling of, for one moment, like you’re connected to someone, even though there’s not another soul in the game.

The highest compliment I can give this game is that it constantly pulls you into engaging with it. And if you’re engaging with a Hideo Kojima game, you’re engaging with Kojima. And for a game that’s all about connections, that’s a very sneaky, rare achievement.

Death Stranding is available on November 8 for Playstation 4 and sometime in 2020 for PC.