The year is 2001 and the music business is under existential threat from the latest teen craze: CD bootlegging. Its response involved draconian fines, an embarrassing txt-speak slogan and Dave Dobbyn made up to look like a burns victim. Robyn Gallagher explains.

Cast your mind back 15 years ago, before the age of streaming and YouTube and The Cloud. Back then music was still almost entirely consumed on physical formats, and the music business’s overriding concern was the continued sale of compact discs. And there was one particularly big threat to this business model: young people with CD burners.

As technology evolved and prices dropped, it became increasingly easy for young music fans to purchase a CD burner and blank CDs and to rip and burn albums for their friends. When record shops were selling new-release CDs for well over $30, being able to buy a copy from a friend for only $10 was so much more appealing.

While this practice was completely illegal, with copying of recorded music controlled by the Copyright Act 1994, the ease of burning CDs made it commonplace. A schoolyard black market grew.

A New Zealand Herald article from 2001 noted that while recordings from Destiny’s Child, Robbie Williams and Britney Spears were the big sellers, “Kiwi music is also holding its own in the playground, with Che Fu and The Feelers in high demand.”

Record labels made the argument that pirating music was hurting the local music industry, but it was harder to convince young fans that millionaire pop stars from overseas, showing off their blinged-out lifestyles in music videos, really needed that extra cash from New Zealand.

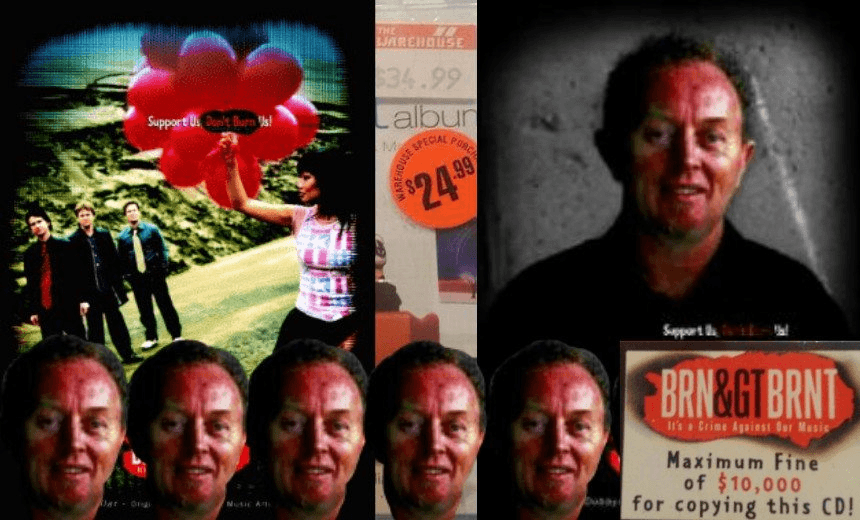

The prospect of teen bootleg CD sellers began to worry the music industry. So in November 2001, the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand (RIANZ) launched the anti-piracy campaign BRN>BRNT (Burn and get burnt). The New Zealand music industry was going after the kids.

In an attempt to connect with its young target audience, BRN>BRNT used txt speak to style its name. And in case you’re wondering, no, BRN>BRNT was never considered a cool name.

The campaign didn’t feel like it was on the side of music consumers. CDs would be festooned with BRN>BRNT stickers, promising a $10,000 fine for anyone caught copying it. The campaign, with its naff slogan, dramatic threats and attempts to be down with the kids, just made the act of illegally burning CDs seem like an edgy act of rebellion.

A number of high-profile New Zealand musicians were dragooned into the campaign, including Dave Dobbyn, Tim Finn and Stellar. But realistically, would a teen fan of Linkin Park or Destiny’s Child really relate to an ad featuring Dave Dobbyn wearing red burn makeup?

I spoke to former CD bootlegger Adam, who was 16 at the time of the BRN>BRNT campaign, and exactly the sort of person who RIANZ was trying to target.

Adam was working part-time, so had money to spend on CDs, usually buying four a week. He would then burn copies for his mates, selling albums from artists like Linkin Park, Slipknot, Jurassic 5, as well as Kiwi bands like 8 Foot Sativa.

He says he’d sell them for around $5 or $10, and always made a point of using good quality blank CDs.

Adam remembers seeing the BRN>BRNT campaign promoted at his local CD store, but it didn’t have much of an effect on him.

“I just wanted my friends to enjoy the music I was enjoying but not all of them had a job like me. I always felt that if anything I was helping to spread artists’ music to those who might not have been able to reach it.”

And his role as a music maven had a long-term benefit. He says, “I still have friends from school who speak to me and say, “Hey man, you got me into [those bands] and I’ve never forgotten it!”

It’s an effect that RIANZ weren’t interested in at the time. They would rather a teen music fan did not buy any music than for them to purchase burned CDs.

The music industry also responded by introducing compact discs with built-in copy protection technology. This caused more trouble, often making CDs impossible to play on personal computers or in car stereos.

Music fan Lawrence Mikkelsen described his dilemma from that era. “I’d take a box of CDs to work every day. The EMI CDs generally wouldn’t play, or would skip badly. As an obsessive music consumer I purchased a lot of CDs, so for three years I didn’t buy a single NZ-released CD from EMI – I’d order them from Amazon UK, where the CDs didn’t have copy-control on them.”

But did the anti-piracy campaigning work? A 2004 New Zealand Herald profile of RIANZ head and departing Sony Music boss Michael Glading notes what while he felt BRN>BRNT was a success, “it mostly inspired people not to burn New Zealand albums rather than albums in general.”

By the mid 2000s, BRN>BRNT had quietly ended, with the music business feeling no less unsettled and uncertain than it did at the start of the decade.

In the press release announcing the campaign’s launch, Dave Dobbyn described an ominous future in which people stopped paying for CDs. “If burning continues to gain momentum,” he warned, “young artists won’t have the opportunities we had.”

Strangely enough, this exactly what has happened. People don’t buy CDs and young artists of today don’t have the same opportunities. But they have different opportunities.

Back in 2001, it would have been unthinkable that an unknown New Zealand artist like Lorde could have made her debut EP free to download, and months later be at the top of the American singles chart.

And the problem that RIANZ was stressing over — kids buying burned CDs — has stopped being a problem because the only people left buying compact discs are music collectors and older people.

Streaming is now the main source of revenue for the New Zealand music industry, making up 35%, with physical sales down to 26%. Why bother leaving the house to pay money for a burned CD when you can stay home and legitimately stream it for next to nothing?

But if anything shows how much things have changed, it’s The Classic Chillout Album CD that Wellington musician Disasteradio came across a couple of years ago. Stuck to the cover was an original price tag of $24.99 (marked down from $34.99) and a BRN>BRNT sticker.

Today, a chillout compilation album can be found on iTunes for as little as $7.99. If you’re a Spotify subscriber, you have the choice of several curated chillout playlists. Or you can listen to a four-hour chillout mix on YouTube for free. No blank CDs required.

The Spinoff’s music content is brought to you by our friends at Spark. Listen to all the music you love on Spotify Premium, it’s free on all Spark’s Pay Monthly Mobile plans. Sign up and start listening today