Lorraine Taylor speaks to NIWA scientist and mum of three Natalie Robinson about a life of science, of travel to a far-away land, and of staying connected to the people at home.

For many of us, the thought of adding a bit of travel to our work-life balance sounds pretty good. For scientist Natalie Robinson, whose research is in sea ice physics, a work trip takes her to the remote southern continent of Antarctica for weeks at a time. It’s extreme work travel with its own extreme challenges, as it means she is away from her three children aged three, five and seven for long periods.

As a parent whose own travel for work is confined to domestic travel – and only an hour’s flight home – the thought of being on another continent, far from home, with infrequent communication and irregular flights back to NZ (even in an emergency) immediately raised my anxiety levels.

Natalie Robinson first travelled to Antarctica in 2003 for her Masters work and made multiple trips there as she studied for a PhD in ocean physics. Travel to Antarctica is not permitted for pregnant women, and while she was breastfeeding and her children were intensely dependent on her Natalie decided not to go. She finally returned last year and is about to leave again for another extended stay on the ice.

It’s becoming a journalistic no-no to ask women about how they balance family and work life. But for many of us it still feels like a valid question. We really do want to know: how does she do it? So I went ahead and asked Natalie Robinson, along with lots of other things I was dying to know about working in Antarctica.

Tell me about your work.

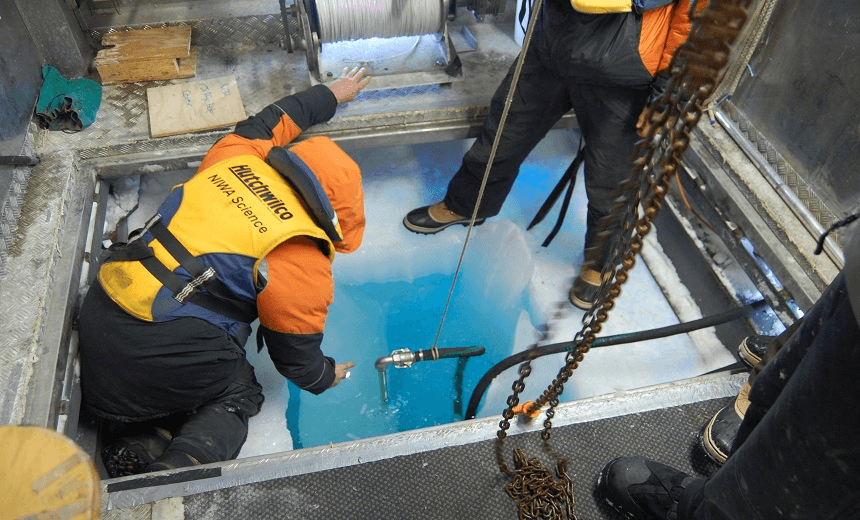

I collect data from the ocean that’s under the floating ice and specifically at the connections between the ice shelf (the fresh ice that’s come off the continent but is floating now) and the sea ice, which is the ocean freezing each winter. They are quite different types of ice… and there are some quite interesting processes that happen in the ocean circulating underneath, when you go from one type to the other.

Possibly the most significant process that happens is that because the water under the ice shelf has come up from a long way down, that change in pressure causes the water to be ‘supercooled’, meaning that it’s below its own freezing point – it should have frozen but it’s still liquid. This produces some quite interesting effects. That’s why we get those thick layers of platelet ice underneath the sea ice. It’s not just the platelet ice, approximately 70 metres of the top of the [Antarctic] ocean is supercooled – it’s the coldest water that naturally occurs on the planet.

Why are you studying the different types of ice?

Some of my work is funded just to increase our understanding of sea ice. But the project has also attracted funding from the Deep South National Science Challenge because we need to know more about how the sea ice and ocean talk to each other for our climate models, and predict our future climate.

What kinds of reactions do you get when people find out you’re a scientist going to Antarctica?

People are really interested, which I find interesting too, as I got all the way though high-school without ever hearing about Antarctica. Now I go to primary schools and talk about Antarctica, and the kids already know quite a bit. It’s a real shift.

People have their assumptions about what it’s like. If it’s a cold day here in New Zealand they won’t let me complain about the cold. But it’s a different cold – it’s so dry that it doesn’t feel as cold. People ask me what’s the coldest I’ve been in and I’ll say -35, but it’s not the same sort of cold. When I say I work in the oceans, people usually think of the animals in the oceans. They’re sometimes disappointed when I don’t know anything about the animals. It’s all about the physics and chemistry. We do make big holes in the sea ice that the seals find very convenient. And we do get to see seals and curious penguins.

People want to know what it’s like sleeping in 24 hour sunlight. They ask whether I’ve seen Aurora – I’ve seen one very faint one at the end of winter, but mostly it’s bright sunlight all the time.

You took an eight-year hiatus from Antarctica in order to have your three babies. How had life changed for you during that break? How were your preparations for heading to the ice different than before?

Last year was the first year that I was primarily responsible for the experiments in terms of planning and executing the science, which was a step up for me.

But on a personal level, my baby was two, and this was by far the longest I was going to be away from her and her brothers. There’s no Skype in Antarctica so it was going to be five weeks that they couldn’t see my face. There was extra planning in order to arrange childcare. I usually spend Wednesdays at home with my daughter, as she’s not at school yet. However, if I’m away, my husband can’t stay at home on Wednesdays. We’re grateful to my mum who makes herself available to come and take my place. This year she’s planning to spend five of the six weeks I’ll be away with my family, so actually I suspect the household will run a lot more smoothly than usual!

We have a few friends who know the kids well enough that they can be called on in an emergency – but we’re conscious that they all have busy lives too, so we try not to make unexpected requests! So apart from my mum and mother-in-law, we have a regular babysitter that the kids love. But my good friend and neighbour (and single mum) has jumped in on three minutes’ notice a couple of times, when there’s been a trip to the hospital involved! We do our best to reciprocate, and between us make sure there’s always a safe and familiar environment for our collective kids.

So you mentioned that trip, five weeks on the ice was the longest you’d been away from your kids. I can appreciate that this was an anxious time for you. What did you do to prepare yourself and that time for your children, or for that time, and what were you concerned about?

I made sure that I would call them frequently from out in the middle of nowhere.

Which sounds easy for us who are connected to our cellphones 24/7 – but it’s not that easy when you are in Antarctica, right?

That’s true – there is no cell phone coverage in the NZ base, and when you are away from the base, you don’t have landline contact either. So there are two ways they can contact us: they can call Scott Base and be patched through via radio, like a walkie-talkie radio, or more recently via satellite phone. I had to make sure I had enough iridium satellite phone time so I could call them every few days.

My kids are pretty robust so it hadn’t really occurred to me that they would miss me that much. That was probably a bit naive of me. I’ll just say that when I got back, they were so excited to have me back. I had to be away that length of time to realise how much they’d miss me, so I’m thinking differently about the next time I’m away.

I was inspired by a tweet you wrote just prior to your departure south last year. You wrote about setting up an advent experience for your children that lasted the length of your trip.

I had this idea that it was going to be a long time away. The plan was 35 days but these things never quite work out exactly so it could be 38 days that I would be away from my kids. I thought it would just be fun if they could have something little from me each day. I thought about a balloon to pop each day and a message of glitter would fall out, but then realised that after a week balloons would start to deflate and it would all be a bit sad. So instead of that I bought a packet of 50 wee noodle boxes and put a different little treat in each – maybe two balloons each for one day, or a music shaker, and other little things that kids like. I also bought them some classic children’s story books, and for those days there was a USB stick in the noodle box with a recording of me reading out a story and a little clue as to where they could find the book. They enjoyed hearing my voice along with having a brand-new book to read.

I strung them up in a pattern in their rooms so when they came home from school, the day before I left there was a surprise waiting for them with these 38 boxes, strung up from the ceiling. During my time away, my husband took some video of them opening the packages and sent it to me by courier.

I have a different plan for this year, that will take even more work, so we’ll see.

Can you give us a little taster, we promise we wont tell…

As long as you don’t tell my kids! I was aware that without me there, perhaps the family life is not as social as it might usually be, so I thought I might ring in all our friends, and have a personal treasure hunt. I might start with a card that says, you have to ring your grandmother on Tuesday, and have a chat to her, and then grandma might have the next instruction – the next part of the treasure hunt – to call our friend Jo on the Wednesday, or something. So, they get the name of the person they have to speak to next, but also the next clue. I haven’t quite worked it out yet, but I think I’m making it harder for myself!

What do you wish people knew about mums who are away for an extended time?

Especially when the children are young, which is my experience now, is that it just wouldn’t be possible without the support from home. My mum and my husband don’t just want to look after the kids – they really want to look after my career as well. That’s a tangible contribution that they need to make for me to be able to do the work that I do.

What lessons have you learnt that could help other parents?

When I made the advent boxes, I recorded songs and stories – I just did that because I thought they’d like it. But actually that turned out better for them than talking to them on the phone. Because they were a bit distracted, and a voice call just doesn’t work so well compared to Skype. But they did seem to make that connection with my voice and a story. It’s what we do every night – our bedtime routine takes over an hour, because we read so many stories and sing so many songs. Trying to continue that even while I’m absent is important. It means they can still have that routine.

*

Aside from admiring Natalie’s gorgeous gift to her children while she was a way for work, I came away from my conversation with Natalie with a realisation. Journalists do, of course, need to aware of their own biases about the roles of mothers and fathers, but there also needs to be space for questions that address the actual lived experience of many women in “balancing” work and primary caregiving.

I believe many mothers do want tips on how to pursue paid work and stay connected to family. And actually, so do men. Like women, men are counting the cost of demanding careers and how they impact on their family relationships. We may be coming at it from different starting points but humans need humans. Family, whānau, our village, and our community matter in our lives as much as our work does.

Natalie’s research will inform us about our changing climate. Her research seeks to answer questions that are still unanswered. It is a gift not just to her family, but to the whole world.

Lorraine Taylor is a Wellington based writer and mum of four, who is still studying and working out what she wants to be when she grows up. Lorraine is currently working in the Science in Society group at Victoria University after finding her niche in science communication, and also works with the Deep South National Science Challenge.

Follow the Spinoff Parents on Facebook and Twitter.