Simon Day sat down for fish tacos, beers and yarns with spearo Ant Broadhead.

Ascension Island is a chunk of volcanic rock in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s 2,250km from the coast of South America and 1,600km from Africa. Other than the island and its British air force base, there’s almost nothing anywhere near this isolated piece of land, except for fish. Lots of really big fish. It was here where Ant Broadhead missed his tuna.

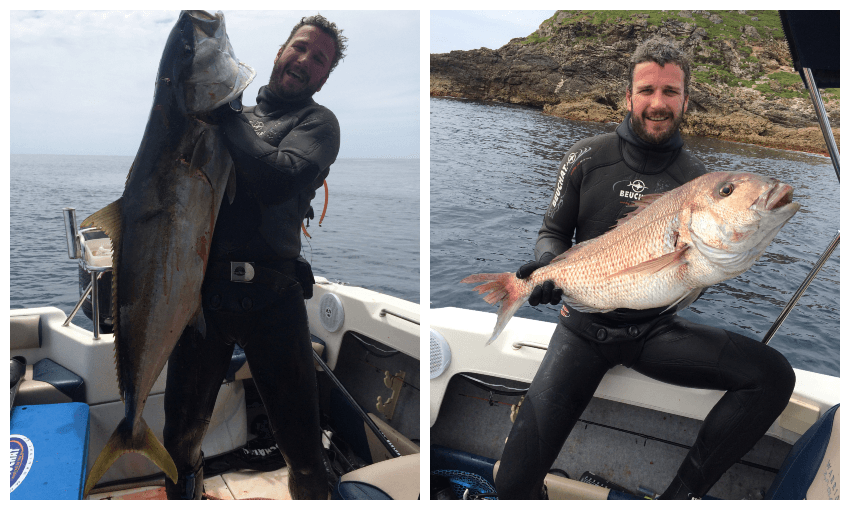

Broadhead is a “spearo” – the endearing term avid spear fisherman use to refer to other members of their tribe. There’s a spark that lights in Broadhead’s eyes as soon as he starts talking about spearfishing. He can’t help his mouth bending at the corners in a smile when he speaks about his love for the sea. It’s the look of someone desperately passionate about something. With a beer in hand, it seems like he could talk endlessly about his adventures beneath the water.

He’s a broad, tall Kiwi lad, with salt and pepper hair and a dark curly beard. He’s always been passionate about the ocean and he grew up boating, fishing and diving. It was while doing his diving instructor’s certificate that he saw his friend playing around with a speargun, and he thought he’d give it a go. He’s been a spearo ever since.

He’s a purist, and this meant when he picked up a spear, his dive tanks were put on the shelf. Traditionally the sport of spear fishing is all about hunting only using breath hold. You take a big gulp on the surface, dive down to swim around and see what you can see, and maybe shoot something. In New Zealand it is not illegal (or frowned upon by the community) to take a spear while using tanks – each to his own – but the purist way of doing things has evolved around breath hold.

In the water, Broadhead found something almost completely unattainable anywhere else in life: the sanctity of feeling completely alone. Combined with the intensity and euphoria of the hunt and the physical test of holding your breath, it was the perfect sport for him.

“Free diving is the only time you have silence, and a bit of peace alone with your own thoughts. It’s pretty special,” Broadhead says.

“There are so many different challenges involved in the sport. It’s a solo sport. When you’re in the water it’s only you and your thoughts. You are competing against yourself, you’re competing against the environment, and you’re competing against another species. Just being in the ocean is epic.”

Resting on the surface, Broadhead can hold his breath for nearly five minutes. But when he’s on a hunt, expending oxygen through activity, and with the addition of adrenaline, this reduces his hold to 60 to 90 seconds. Under the stress of a big hold, it’s a unique physical experience.

“When you hold your breath and you feel that feeling in your throat, that is only the first warning of your body telling you to take a breath. If you go through that, it’s the best feeling ever. It just gets better and better. It’s really euphoric.”

When you really push it, everything starts to turn warm and tingly and nice, and you get lost in your own thoughts. That’s where you have to be careful.

“When you’re hunting you’re still aware of what’s going on and you have to stay focused. And if you push it too hard you have a long recovery time, so you have to find that right balance so you can dive all day.”

The hunt is a stalk. A spearo will usually go out for six or seven hours, usually with a specific species in mind, and dive to different areas to target those fish. Each species is a unique challenge. Different types of fish require individual hunting techniques as they react differently to the presence of a human in the water. A lot of the hunting is done in pretty shallow water near the coast. They’re looking for areas where fish are holding, whether they are sleeping or resting, or actively feeding.

“Snapper, for example, as easy as it is to catch them on a line, it’s really hard to shoot them. They are a really spooky fish and they just scatter. You have to start down current from them so they can’t pick you up. It’s part of their electrical scent. They’re just aware that you’re there. Even a little noise will trigger them and they’re gone,” says Broadhead.

Kingfish, on the other hand, are really inquisitive and a bit dumb. They will school around a diver and can be shot without even leaving the surface.

“Kingfish is more about the fight. They are a really powerful fish. Power-to-weight ratio, they’re as powerful as a marlin or tuna.”

And then there’s the marlin. They’re an incredibly powerful fish. They’re aware of their size and often get really close to the spearo, but they’re never aggressive. With these fish it’s about the fight. When you shoot tuna they dive deep, while marlin will run and can tow a spearo and their float system two or three kilometres around the ocean, just holding on.

“If you compare it to line fishing, these guys can take four, five or six hours to land these fish. Most spear fishing you’ll land the fish within half an hour absolute max,” he says.

In the South Atlantic around Ascension Island the fish get really big – the tuna are over 100kg and the marlin even bigger. On their trip, Broadhead’s friends had both shot giant tuna. And then a beautiful yellow fin tuna appeared in his vision.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t hit the sucker.”

During my lunch conversation with Broadhead I ordered kingfish tacos and one of Monteith’s Pointer’s Pale Ales. I wanted to appear down with the spearo crew by eating kaimoana. But this revealed something about Broadhead that was initially very perplexing. He doesn’t eat seafood. In fact, he can’t stand it.

But, this quickly provided clear insight into the mindset of a spearo. Not that they don’t eat fish, but they think holistically about how their sport impacts the environment.

“I do it for the pleasure of being out in the ocean. I’m really selective about what I want to take. If I’m out there for six hours and there’s no fish I want to shoot, I’ve got no issue with it,” he says.

“I’ll knock over a small fish to feed my family. If I shoot a big fish I’ll prep it at home, fillet it, bag it and drop it off at a mate’s house. It never goes to waste.”

The health of the ocean and its ecosystem is deeply important to the spearo community, and Broadhead is proud that spearfishing is the most sustainable way of taking fish. It’s also more humane than line fishing. A spearo is trying to hit the fish right across their lateral line, aiming at either the brain or the spine. And if you get it right, the fish is dead almost straight away.

“You can be really selective. It’s up to you if you pull the trigger or not. There’s no chance of shooting an undersized fish and there’s no throwback,” he says.

There are also certain ethical rules and understandings of what fish species you do and don’t shoot. These are rules created by the community to manage their impact on the sea.

“A lot of fish we have in New Zealand only come past occasionally, like groper, and these are certain fish you don’t want to be shooting. Red moki, for example, they mate for life and only have one partner, so if you bang off one of them then old mate’s going to be alone for the rest of their life.”

It’s that passion for the ocean that attracts a broad demographic to the community. Farmers, young adults, accountants, lots of women, and an older generation too – legends who love to talk about “back in my day” – and this creates a community that is closely engaged in supporting each other and the sport. They look after new people keen to try it out, and there’s always someone to put their hand up to take people out on the ocean, show them around the reef and have a beer at the end of the day.

“There are a few dangers involved. There are a few things that can go wrong. You’re pissing off into the ocean for hours. And you’re pushing your body to the limits as well in terms of holding your breath. That can go a bit pear shaped. You want everyone to be safe and aware,” Broadhead says.

Sharks are the famous arch rival of the spearo. Broadhead has seen “shitloads” while out hunting, and rather than fear them, he knows they represent a good sign for the ocean, the sign of a healthy ecosystem.

In New Zealand’s waters we get a lot of bronze whalers, and he’s swum with a number of mako sharks. He sees sharks most times he dives. And if they ever go after a fish he’s shot, it’s a spearo’s obligation to defend their catch.

“You dive down on the shark and give them a jab,” he says.

“I’ve had a few hairy moments, especially when you’ve got packs of sharks around you and you have to hop out. You get bumped and rammed occasionally.”

What is Broadhead’s favourite fish to shoot? It’s a hard choice. The fish that stay deeper like the boar fish are a challenge (and they’re great eating fish). But the elegance and the challenge of the snapper is still probably his favourite.

“You see them in the water with their big wings out, and they’re just so hard to catch.”

And it’s so much more than just the hunt.

“I love going out and experiencing what’s in the ocean. You’re just out there lost in your own thoughts, then an 80kg stingray swims over you. In Ascension I had a 12 metre whale shark sneak up on me. I didn’t know it was there until I felt it against my ribs. That’s so cool.”

This article was brought to you by Monteith’s. Monteith’s Phoenix IPA will be sold as 330ml 12 packs (5.0% ABV), RRP $24.99 and is available at supermarkets and liquor retailers around the country.