The pandemic exposed inequality in different communities, but it also revealed solutions. This is the first essay in a new series examining the effects of Covid-19 on New Zealand, in partnership with Te Pūnaha Matatini.

By Anna Matheson, Krushil Watene, Grace Vujnovich, Turei Mackey.

The kids sang and danced. Parents and supporters carried trays of food to the school hall. A fabulous cloak, sewn by grateful community members, was presented to the committed and generous lawyer who had worked pro bono. We were celebrating the end of a long campaign by the school and local community to prevent a liquor store from operating.

The liquor store, across the street from the school, was damaging the community. To stop vandalism to school grounds, a three-metre-high fence was built. The school gates had to be locked on evenings and weekends. Children told their parents they felt unsafe walking to and from school. One local family had to cut down the tree in front of their property because it had become a magnet for late-night drinking and was being used as a urinal.

The closure of this liquor store was hard-won. It had taken the whole community and its advocates to get to this point: teachers, residents, a prominent lawyer, Regional Public Health and the NZ Drug Foundation. The school community felt much safer.

But why did this community need to spend their scarce and valuable energy and resources and doggedly fight to correct such an obviously destructive situation? The kids’ schooling could have done with this energy – a new playground or sports equipment would have been more uplifting than a fence. The ultimate injustice, it turns out, was the need for this community to do all the heavy lifting.

Most of our health and wellbeing is created within the places we are born, live, work, play and age. The evidence from the World Health Organisation’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2008 was unequivocal about this. It also left no doubt that unequal access to resources and power is the leading cause of health inequity globally. Across Aotearoa, this is no different.

Decades of research has shown how inequality plays out in some communities. Adequately paid and safe employment is scarce; schools are under-resourced; homes are not fit to maintain health; green spaces are limited; playgrounds are neglected; plentiful retail and fast food outlets advertise and sell harmful products; and healthcare is difficult to access. Because of this, health outcomes remain unequal.

This lack of change in communities sits in stark contrast to constant change within the policy environment. The health sector itself has been in almost continual reform over the past 20 years, causing a discontinuity in priorities, people, relationships and structures. This discontinuity has made it difficult for successive governments to act with continuity over time, drawing on long-term knowledge of communities, their needs, aspirations and contexts. Instead, communities are treated as passive recipients of policies and programmes, rather than as active agents of transformation and change – which has undermined local self-determination.

The Covid-19 crisis has raised the voices of communities. In many places, it has revealed what more sustainable community ecosystems could look like: less traffic, more greenery, consuming locally, better urban design, taking greater care of the natural environment.

Covid-19 has also shown that, for some communities, barriers to local action are more fundamental and closely tied to the broader determinants of health, including income. The extent of this vulnerability was seen in a report from the Commission for Financial Capability, which showed in March and April’s level four lockdown “34% of households were in [financial] difficulty and 40% were at risk of tipping into hardship”.

In other countries, “community wealth building” has been gaining traction as a people-centred approach to redirecting wealth back into local communities. In North Ayrshire and Preston in the United Kingdom, local councils have implemented policies to create fairer labour markets and shift power to communities – providing greater fiscal control, increased authority over land ownership, and strengthened local democracy and governance.

In Aotearoa, well before the pandemic, a groundswell of innovative community action was under way. Local organisations are tackling public health concerns such as harms caused by alcohol and tobacco, prevention of chronic diseases, strengthening local food systems, and improving local service, physical and natural environments.

Alongside renewed understandings of communities as complex systems of relationships, communities themselves are embracing methods of collective impact. Across Aotearoa, local perspectives on local systems are being valued and acted on — something Indigenous peoples have long practised.

Community as complex systems of relationships

Māori responses to colonisation are built around community. Indigenous models of health and wellbeing such as Sir Mason Durie’s Te Whare Tapa Whā and Te Pae Māhutonga have grown in prominence, increasingly supplanting narrower western-derived understandings. These models are contributing to global recognition that the environment is central to human existence — instead of being an afterthought, an externality, or an infinite resource able to support exponential economic growth.

In Aotearoa, progress is being made to take action grounded in this paradigm. In South Auckland, for example, Star Compass: Te Kauae is revitalising Māori practices by normalising indigenous knowledge and reconnecting rangatahi to who they are and where they are from. Ngāti Manu, a hapū of Karetu in the Bay of Islands, is working in partnership with Far North Holdings to protect the mauri (life force) of the Taumārere river. They are leading community activities such as opportunities for young people to get involved in planting and pest management.

Drawing on natural rhythms of maramataka (the cycle of the Māori lunar calendar), iwi, hapū and community are being connected. A focus on wairua and hinengaro (spiritual and mental) wellbeing is guiding initiatives in Whanganui to inform suicide prevention and mental health strategies. In West Auckland, schools are developing practices to teach necessary skills such as planting kai and encouraging tamariki to learn their whakapapa through pepeha. In Rotorua, during March and April’s lockdown, Te Arawa Covid-19 drew on rāhui (a temporary ban) and ringawera (recognising all the essential workers) to help ensure correct information, essential food and medicines reached whānau.

Amid a growing desire for greater food sovereignty, communities are deciding for themselves that they want to transition to low-carbon and sustainable futures. One example is the Pā to Plate project, which is reconnecting Māori with their marae in Northland and the central North Island by enabling descendants to purchase produce from their whenua. Another initiative, the Good Food Road Map, developed by The Southern Initiative and Healthy Families South Auckland (one of nine Healthy Families NZ locations), has been designed to spark a nationwide movement to build local food systems that are regenerative, inclusive and resilient.

In Aotearoa, Māori and Pacific cultural concepts and practices have always valued relationships in connecting the present to the past, communities to one other, and humans to the environment. But the understanding that communities are complex systems of relationships is not yet widely reflected in policy decisions and actions.

We have plenty of evidence showing that how we invest in community health is essential for effective collaboration. We know, for example, that community health and social service providers frequently find themselves pitted against each other due to competitive and siloed funding requirements. These disincentives to cooperate result in limited sharing of information and data, duplicated services and inconsistent messaging within local communities.

In response, Healthy Families Waitākere is disrupting this system and facilitating high-trust relationships throughout the local network of diverse Pacific organisations and collectives. This initiative draws on Pacific concepts of reciprocity to strengthen relationships and support collaboration between these groups. This cross-organisational information sharing has already led to tangible outcomes, including the phasing out of sugary drinks in Pacific churches and community groups across the region.

Two current government initiatives working across multiple communities have also resulted in successes like better access to services and healthy changes to local environments. Whānau Ora is linking up local health and social services to improve how they are delivered to whānau with multiple needs, and Healthy Families NZ is facilitating collective community action to improve community health and wellbeing.

These are rare examples of policy that takes a complex systems view of communities. In both cases, funding, contracting and reporting have been set up to be responsive and allow adaptation to local needs. However, the creation of wider system change still faces significant challenges: community-led initiatives such as these continue to be undervalued, limited in reach and under-resourced relative to other public spending.

Communities working together on collective goals

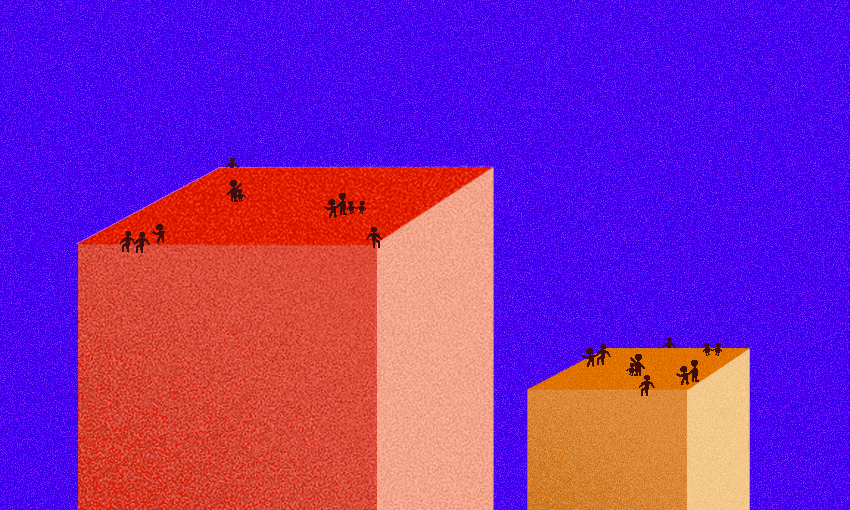

How communities organise, and how they are organised, matters for health, wellbeing and equity. Socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are largely reliant on “manufactured organisation”: organisation that is created through health, social and economic imperatives and policy strategies forced upon them.

The situation is different for wealthier communities, where local organisation emerges in a context of pre-existing wealth, relationships with decision-makers and power structures. In communities like these, a liquor store would never have been able to open in the first place, across the road from where community members’ children learn and play.

Models that guide “collective impact” highlight the need for shared infrastructure, insights, resources, information and ways of measuring success. For this cooperation to be effective it is also important that they are supported by a dedicated “backbone” organisation. These approaches offer much promise, but only if they can address large-scale challenges at the same time as fostering deep connections into grassroots communities.

We know that small local changes can be contagious. Since 2016, Healthy Families Waitākere has been supporting a movement to improve access to water and disrupt the consumption of sugary drinks in schools and clubs throughout West Auckland. With the support of principals, teachers and board members, students have been key to driving water-related changes in their schools. This student-centric approach has seen more than 50 West Auckland schools develop a water pledge, as well as receiving support to access essential funding for the improvement of water infrastructure on school and sports club grounds.

In Invercargill, similar success has been achieved through codesigning a set of guidelines to make community events healthier. Choice As Events pledge to be free of sugary drinks and deep-fried food – the local Murihiku Marae even issued a wero, challenging other marae to become sugary-drink-free too. In Lower Hutt, local neighbourhoods are acting to make better use of their local streets: Naenae is trialling making free bikes accessible to all for local journeys, Epuni is working on a ReCycled Rides initiative, Wainuiomata is linking with college students to improve bike maintenance and riding skills, and Taita and Pomare are redesigning their local park as a safe place to walk and cycle, and creating a base for bike repairs and bike skills training.

It is important to understand that different solutions are needed to meet the unique needs of communities in different places and situations. Small changes within communities can be built upon, and lessons learned for future action.

Our policy past has led to where we are now

The disruption of Covid-19 has caused communities in Aotearoa to be more vocal about what they need – and what they need is a change in their relationships.

A collective of charity and non-profit organisations recently laid out what this change might look like. Along with more generous, compassionate and empowering social policies, the Please Press Pause paper submitted to the government by the Wise Group asks for a more agile government, longer service contracts (five-year instead of annual reviews) and flexible funding (enabling collaboration and covering uncertainties), with funders and providers working together to measure what is important.

The type of relationships which exist between organisations that act locally – service providers, iwi, charities, NGOs and government – matter. Collective, collaborative, insight-gathering approaches to improving community wellbeing hold promise; but in practice, their implementation has been piecemeal and inequitable.

Aotearoa’s highly prescriptive government contracting environment – one of the legacies of the 1984 neoliberal reforms – still limits our public sector’s ability to deal with complex outcomes. Responsive contracting models and the task of putting policy into action have long been undervalued. This situation was made worse for communities by a widely held view that the purpose of welfare is to determine to whom government should provide money and other services – with little debate about the how. That perspective still dominates, despite rhetoric since the early 2000s of partnership as a means of delivering social goals.

The rise of partnership approaches was spurred by an emerging recognition of the community or “third” sector within the United Kingdom in the late 1990s, when social inclusion, exclusion and inequality came into focus. In Aotearoa, we also recognised “partnership” in relation to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. But despite progress, we know full justice for Māori has not been realised. Even amid the Covid-19 crisis, many Māori have rightly questioned whether real partnership has been enacted in the pandemic response. This is a familiar pattern for policy action – responsibility may be devolved, but not real power and resources.

Persistent and entrenched inequality in the United Kingdom – which is clearly influencing health and social outcomes resulting from the pandemic – has led to calls for a radical rethink of their public sector. Advocates have pushed for a move towards greater localism and community wealth building, where local government has more responsibility for local wellbeing. In Aotearoa, it is enlightening to see that many community initiatives involve local councils, either as a partner or as a target for change. Already the Local Government (Community Well-being) Amendment Act 2019 provides an opportunity to strengthen local governance. The act gives councils the power to change their priorities and ways of working. They already hold power to act in the interests of local wellbeing.

‘The community ecosystem flourishes when system constraints are removed’

Removing constraints on local action is not straightforward and does not mean getting rid of top-down influence. It is about appreciating the complexity of these relationships and doing things differently. Political will and evidence-informed policy goals are necessary for creating the conditions for communities to flourish.

To date, governments have been slow to take bold and effective action on industries that create a lot of harm – such as alcohol, parts of the food industry, and those with high carbon emissions. And where substantial action has been taken – for example, the tobacco industry – even with overall improvements in population health, outcomes still fall unequally. The poor and Māori continue to endure disproportionate harm from tobacco. The Covid-19 crisis further underscores just how easily inequality is reproduced.

But communities experience differences in the ease with which top-down policy can be adapted to local needs, and whether those with power will share it. Increasingly, district health boards and local councils are recognising their important role as anchor organisations within their communities. Some have been providing support for the expansion of smoke-free policies to local areas, while others have changed their procurement policies to favour local businesses, for example in catering or construction. Many are also now looking to their own environmental and sustainability practices, aiming for more responsible waste disposal and efficient and sustainable energy use.

In Christchurch, there has been some local success at adapting to weak and generic national alcohol policy. A local collaboration to reduce alcohol harm and antisocial behaviour in sporting environments resulted in an unintended and even more useful change to the Christchurch City Council alcohol bylaws. This turned a temporary sideline ban on alcohol consumption into a permanent ban applying to all sidelines, changing rooms, carparks and children’s play areas.

Centrally driven, top-down policy action is necessary – but not sufficient on its own. Our policy systems tend to favour the identification of problems over the complex task of implementing solutions. Largely rigid and competitive investment strategies have left little room for flexibility and uncertainty in the delivery of policy goals.

Aotearoa’s short three-year political cycle and polarising ideological stances on the role of welfare have impacted how government relates to communities. And our attempts at devolution have not always occurred as intended, whether small (such as service contracts) or large (such as health sector restructuring). Perhaps this is partly because it is local communities that need to be regarded as the “centre”.

The finger is pointing squarely at the public sector to get its act together, and there are signs it might be trying. A Public Service Legislation Bill is currently before parliament. It recognises the need to address the impacts of earlier reforms that have made effective intersectoral and whole-of-government action more difficult. Hopefully, it will also pay heed to the opportunities the Covid-19 pandemic has provided: to really listen to the needs and aspirations of communities, to refocus policy action on the how, and instead of prescribing change, to foster the conditions to enable local wellbeing.

Lessons from our growing numbers of “collective impact” initiatives show they could well be scaled up. The public sector could change its view of itself and operate as the “backbone” to support community organisation – a steward and facilitator, rather than a decider and enforcer. To do this, we need responsive policy organisations, not just policy products.

We have recently hit the population milestone of five million – a number that will undoubtedly grow. The challenges of evolving populations are frequently unknowable without deep roots in communities. If we can reorient our systems to be more locally adaptive and intimately focused, we can enhance wellbeing by reducing the burden of preventable diseases on our health system, improving equity, and reconnecting to the natural world which sustains us.

It is clear that communities can achieve a lot with the right guidance and relationships. But the cost of change in many communities is currently too high. The energy and resources needed to prevent that liquor store from operating across the road were not a fair price for the school community to pay.

Anna Matheson is Senior Lecturer in Health Policy at Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington. Anna has a background in public health and equity and is interested in effective ways to achieve better community health and wellbeing.

Krushil Watene (Ngāti Manu, Te Hikutu, Ngāti Whātua o Orākei, Tonga) is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Massey University, specialising in moral and political philosophies of well-being, development, and justice with a particular focus on indigenous philosophies.

Grace Vujnovich is a storyteller and systems change communicator with Healthy Families Waitākere in West Auckland.

Turei Mackey is a Strategic Communications Manager with The Southern Initiative and Healthy Families South Auckland.