Watching the New Zealand election from London, Jono Hutchison is getting a bit of déjà vu. What follows is a cautionary tale of two conservative governments picking fights with human rights.

Bill English and Paula Bennett yesterday announced a big crackdown on methamphetamine and gangs. The plan came with a big price tag – $82 million – and a big call: that gang members who had particular convictions could be subject to warrantless searches. That’s a big call because it may violate Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“It probably does breach the rights of some of those criminals,” Paula Bennett admitted. And when she was pressed further, she said that it was nevertheless the right thing to do because the people she was talking about had “fewer human rights than others when they are creating a string of victims behind them.” The prime minister said that it was “good” that New Zealand doesn’t have a written constitution to get in the way of such policies.

This morning, Bill English has said Bennett got it wrong, but already the statements had alarm bells ringing. This was the “slippery slope to fascism”, a human rights lawyer told Stuff. It represented “the National Party of old’s coffin lid creaking open, a zombie back out to fight an election in 2017,” wrote the Spinoff’s Duncan Greive. From over here in London, it just felt eerily familiar. Stay with me – here comes a spooky political comparison.

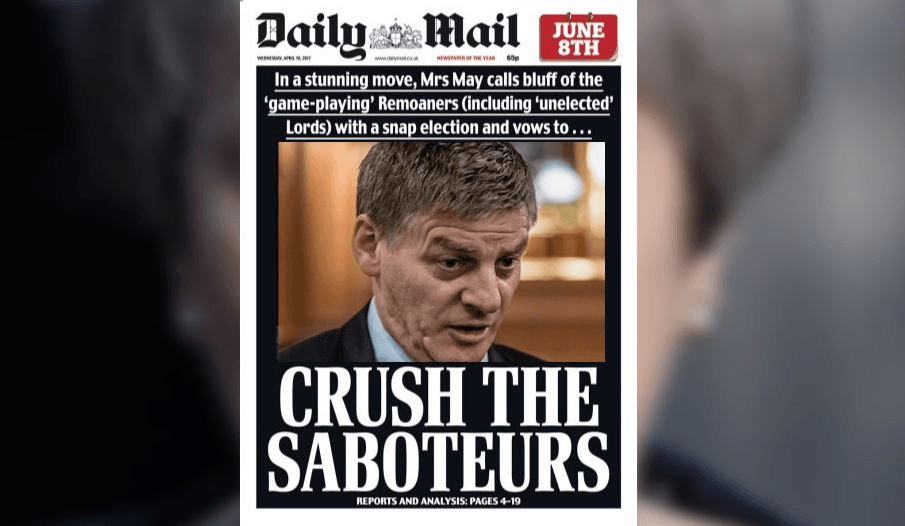

Just a few months ago, Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, was also facing an election as the incumbent. When she called the election in April, she had seemed undefeatable. Political pundits, <sarcasm> famous for being the most accurate and well-respected type of pundit </sarcasm>, were predicting historically bad results for Labour – even the destruction of the whole Labour Party itself. The Daily Mail was very chill about it all, as you can imagine.

Theresa May had managed to consolidate her strong position in part by pushing into the political middle as Jeremy Corbyn took Labour further left. Since taking over from David Cameron (remember him? He thought it would be a good idea to let everyone vote on Brexit because they’d never vote for that) as prime minister, she had talked about setting “our party and our country on the path towards the new centre ground of British politics”. She decried the “privileged few” and promised to build a Britain that worked for everyone – a clear play for swing voters and those in the centre-left who felt disillusioned with the direction of the Labour party. And it seemed to be working.

But then the campaign got under way, and the “strong and stable” candidate started to fall apart. Theresa May was tested and found wanting. She was criticised for refusing to take part in televised debates and for failing to articulate a strong vision, while Jeremy Corbyn had a story to tell of how Britain could be different – and a lot of people liked that story.

In just a few short weeks, what had seemed like an easy win for the Conservative government was turning into Corbynmania, and the polls were narrowing. Sound familiar? Perhaps a bit like an election in the southern hemisphere? Does it sound like what’s happening in Aotearoa New Zealand or what, help me out here?

It was in this atmosphere that Theresa May gave a campaign speech on June 6 in Slough, the town famous for being home to David Brent’s branch of the Wernham Hogg Paper Company in The Office. Speaking just days after the terror attack at London Bridge, which left eight victims dead, and not long after the Manchester Arena attack, in which 22 died, May turned her attention to terror.

“We should do even more to restrict the freedom and the movements of terrorist suspects when we have enough evidence to know they present a threat, but not enough evidence to prosecute them in full in court,” she announced in her speech. But wouldn’t that breach human rights, you may wonder? She continued: “And if human rights laws get in the way of doing these things, we will change those laws to make sure we can do them.” Oh.

The country was still in mourning after the attacks and there was pressure on the prime minister to show leadership. In times of trouble people often look to political figures for answers and resolve; the prime minister decided to respond by vowing to demolish human rights laws if they got in her way. She was trying to show she was in control but it felt desperate – and it didn’t work.

When you’re playing for swing voters and centrists, I would humbly suggest that directly threatening human rights is probably not what they want to hear from you. And Britain has a proud history of continuing on with a “stiff upper lip” in the face of adversity – so if no terrorist is able to defeat the freedoms this country holds dear, then suggesting that the government might respond by curtailing freedom just doesn’t seem smart.

As it happened, more and more voters jumped on the Corbyn Train, despite the polite and chilled out suggestions from newspapers as the nation went to the polls.

Theresa May did go on to win the election, but only by a very narrow margin, forcing her to work with a very minor party from Northern Ireland in order to secure the votes she will need. She ended up far weaker than she was beforehand – and Labour continued to surge in the polls post-election, eventually overtaking the Conservatives (bit late, but still).

So there you go. A tale of two conservative governments picking fights with human rights. The situations were of course different, but I dare say the strategies are similar: to play the bad cop card in order to look tough on baddies.

As for whether the same election result will happen in New Zealand, I certainly wouldn’t like to guess. But I will say this: it’s a pretty interesting comparison, right?!?!?