Danyl Mclauchlan makes the case that what the new leader of the opposition doesn’t say matters – and what he does say probably doesn’t.

In all of our parliaments since 1996, when the electoral system was changed from first past the post, there’s been competition and diversity in opposition. When Labour was last in government the ACT Party was a party instead of whatever David Seymour is and the National leader had to compete with Richard Prebble and then Rodney Hide for voters and media space. When National were in government, Labour, the Greens and New Zealand First were in opposition. When Labour’s leaders performed poorly Russel Norman and Winston Peters competed for unofficial “real leader of the opposition” status. And the Greens were always in opposition, no matter who governed. Until now.

Although we currently have a very MMP-style arrangement with the second-largest party forming the government instead of the largest, this is our least diverse parliament in terms of seat allocations since the introduction of MMP. Eighty-five percent of the seats in the house are occupied by the two major parties. It’s a ratio that’s been creeping up – albeit unsteadily – over the past 22 years and it will be interesting to see if it constitutes a trend with National and Labour increasingly dominant in our politics, or if some correction kicks in and there’s a resurgence of small parties. Or maybe this is just a variable that jumps around randomly in the chaotic system of parliamentary politics.

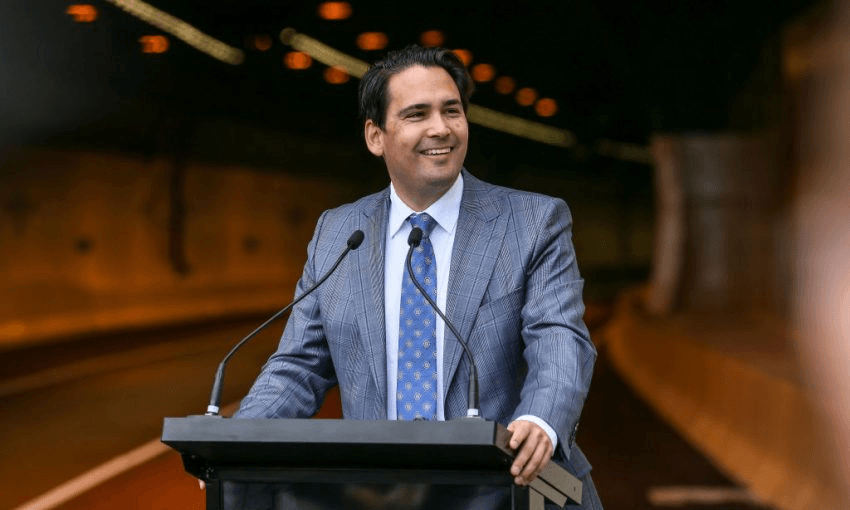

Right now it means the opposition is just one party. Why does that matter? Firstly, it will make life easier for Bridges: he can compete directly with Labour without the bother of some rival right-wing party trying to peel off National votes. But it also matters because the opposition helps determine what is and isn’t political news.

Two weeks ago saw the publication of a handful of columns revealing that Jacinda Ardern appointed a former Sky City lobbyist as her chief of staff during the transition and first five months of her new government, and that they’ve now shifted back into professional lobbying, a jaw-dropping conflict of interest that would be illegal in many other advanced democracies.

If such a thing happened during the Key government there would have been a huge outcry: protests, online petitions, twitter hashtags, Radio New Zealand flooded with academics lamenting the death of our democracy. Instead there was an indifferent silence, which helps validate my pet theory that despite all the talk about policy and values, much of politics is just professional wrestling for bored nerds, but it also highlights the difficulty of getting traction on a political scandal if the opposition sees no advantage in it.

National has no interest in progressing such a story because they in many ways spent the last nine years acting as a vertically integrated lobbying and fundraising operation, and their former chief of staff is now a consulting partner with the same lobbying firm as Labour’s former chief of staff. Nor do they have to front on the story, because no other opposition party exists to compete with them for media space. Most government scandals need opposition leaders asking questions in the house, crafting lines so that the voters can understand what’s happening, providing optics for the TV news, and having their research units breaking new angles to keep the story live. If none of these things happen then there’s no scandal.

So where will criticism of politics-as-usual come from in our current parliament? Maybe some other party will fill the opposition vacuum? MPs sometimes split from their party, particularly if that party is led by Winston Peters, but the waka-jumping bill is designed to prevent this. Previous minority parties in coalition sometimes have the bright idea of differentiating themselves by attacking their own government, a move that inevitably leads to internal caucus conflict, coalition instability, voter confusion and the rapid death of the minor party, so we’re unlikely to see either New Zealand First or the Greens deploy the tactic. Perhaps TOP will emerge from Gareth Morgan’s smoking ashes? Perhaps some other third party hero will rise?

There’s still the 5% threshold before TOP or any other new arrival can enter parliament. That’s a very formidable barrier for a party that isn’t already there, campaigning with all the elaborate perks and funding and staff that come with the privilege. Back in 2012 the Electoral Commission recommended that the threshold be lowered to 4%: the then justice minister Judith Collins thought otherwise and the recommendation was ignored.

Labour has an interesting dilemma there. It competes with both of its coalition partners for votes so it wouldn’t be a bad thing for Labour if they were wiped out. That’s the long run though: there’s a plausible nightmare scenario in 2020 where enough Labour-available votes go to NZ First and the Greens for them to each get just under 5%, costing Labour a majority and both its viable partners, putting National back into government and making Simon Bridges prime minister. Labour could decide to adopt the Electoral Commission’s recommendations – purely on their merits, obviously – as an electoral lifeline.

In their submission to the Electoral Commission New Zealand First opposed lowering the MMP threshold. They might change their minds if they continue to poll under that mark, but if they stick to that then the government won’t have the votes to change the threshold. But by 2020 the prime minister will be campaigning with a toddler as her de facto deputy co-leader: it probably won’t matter what happens with lobbyists, thresholds, the minor parties, the coalition, the opposition leader, or what other dubious behaviour the government engages in if National is disinclined to critique it and there are no other critical voices in our parliament.

This section is made possible by Simplicity, the online nonprofit KiwiSaver plan that only charges members what it costs, nothing more. Simplicity is New Zealand’s fastest growing KiwiSaver scheme, saving its 12,000 plus investors more than $3.8 million annually in fees. Simplicity donates 15% of management revenue to charity and has no investments in tobacco, nuclear weapons or landmines. It takes two minutes to join.