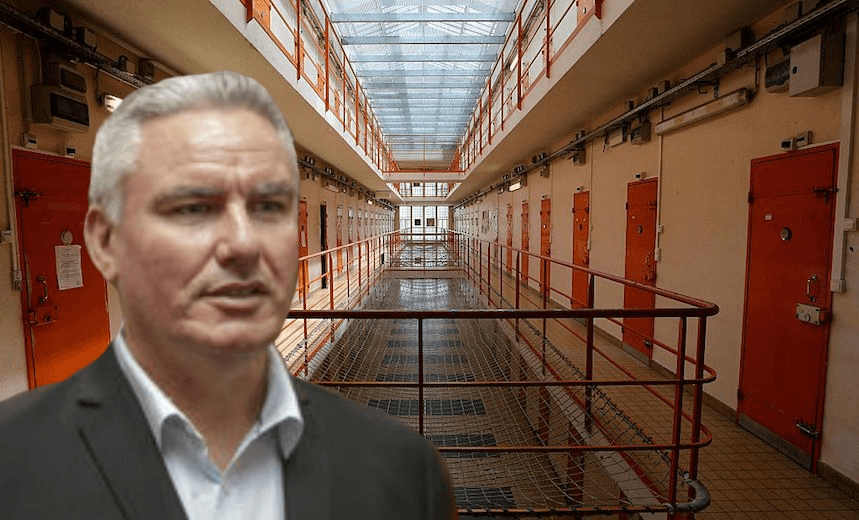

New Zealand’s prison population is ballooning, and no politician seems to have any good plan to stop it – except Labour deputy leader Kelvin Davis, writes Di White.

For almost two decades there has been a ring fence around prison policy in New Zealand. It’s a high fence – you can’t climb over it by pointing to clear evidence or international best practice, or by appealing to common sense or fiscal prudence. It’s one that politicians of both persuasions have politely respected, not daring to give it a tap to assess its strength or peek through a crack to see what’s happening inside. For years, Garth McVicar loudly and proudly paraded up and down its perimeter, a constant reminder that if a politician dares to climb over they would face the full force of a Hawkes Bay farmer wearing a polo shirt and boat shoes.

Behind the fence, the prison population and flow-on government spending has been ballooning. Sky rocketing. Exploding into the sky in an impressive show of human suffering and fiscal wastage. Business has been booming under National, if you’re in the business of building prisons. But National does not have a monopoly on punitive prison policy. Between 2003, soon after Labour introduced a raft of legislative and policy changes with the stated purpose of increasing the prison population, and 2017, with National doggedly standing by its decision to spend over $1 billion on more beds, the prison population has almost doubled from 6,300 to 10,200. Politicians of both sides have all but sat there with a bowl of popcorn, shrugging at each other as if to ask what they could possibly do to turn this ship around.

Until Kelvin Davis. Since taking the reins as Labour’s corrections spokesperson in 2014, Davis has pushed past the posse of equivocating politicians and stormed the fence down. “One thing I do know,” he says in one of his frequent and refreshingly bullish posts on the state of New Zealand’s prison system, “[is that] our Corrections system is the closest we get to building a bonfire and unquestioningly throwing tax-payer cash into it, to keep it burning indefinitely.”

Following the demise of former corrections minister Judith Collins, Kelvin Davis has become one of the most prominent figures in the New Zealand’s prison debate. In 2015 he was the face of the campaign to bring down prison provider Serco after he surfaced instances of abuse and mismanagement within the privately-run Mt Eden remand prison. Serco subsequently lost the contract to run the facility, and the debacle put a dark cloud over National’s private prison model.

Davis then rose to international prominence when he travelled to the Australian detention centre on Christmas Island, where large numbers of New Zealanders faced deportation following a shift in Australian immigration policy. It was a move that made headlines on both sides of the Tasman, with Davis launching a scathing attack on the Australian government’s treatment of people in detention, calling it “a violation of human rights”. “Those fences and gates that are keeping people in are also keeping scrutiny out,” he said, during one of his visits to the centre. With an international human rights community that often tiptoes around Australia’s treatment of people seeking asylum or otherwise detained in detention centres, Davis was the grenade that many had been waiting for.

For Davis, the issue of prisons is, at its heart, an issue about the treatment of Māori. Despite making up just 15% of the population, Māori currently make up 50.9% of the prison population. In 2016, 56.3% of new prisoners were Māori – the highest proportion since records became available in 1980. It’s a statistic mirrored across a number of colonised countries, where indigenous populations are disproportionately over-represented in prison numbers. Prisons as we know them in New Zealand are based on an antiquated English model of punishment that has patently failed many communities, but in particular failed Māori.

There is a natural tendency to link crime and prisons, as if the former drives the latter. Rather, the prison population – both in its size and cultural composition – is driven largely by policy and legislative settings, not by what is happening in our streets and in our homes. Politicians set the parameters that judges apply. If we change the parameters, we change the prison population – as we have witnessed in recent decades, when a relentless stream of ‘tough on crime’ policies and laws has driven the increase in prison population.

Given the current make-up of our prisons, any approach to reducing the prison population will necessarily be rooted in solutions that acknowledge and respond to the ways in which policies, systems and laws disproportionately target and imprison Māori. This needs to be a conversation led by Māori and supported by a whole-of-system focus on what will lead to fewer Māori coming into contact with the justice system, let alone being sentenced. While Davis’ idea for a Māori prison sparked controversy, it demonstrated the lens through which he will seek to address this problem – one that squarely puts Māori needs and interests at its centre.

Labour’s policy announcements have so far been all but silent on criminal justice policy. Other than 1,000 additional frontline police – a commitment that will significantly fuel rather than stem the prison population – there is no clear plan to tackle prisons. Indeed, Davis’ announcement-not-announcement of a prison run on tikanga Māori values was quickly quashed by then Labour leader Andrew Little. Until now, a question mark has hovered over Labour’s corrections policy.

While Little had an interest in justice issues, a bold new direction on criminal justice policy seemed unlikely under his leadership. Indeed, it hardly seemed plausible that it would be an area where Labour would lead or actively court debate. It’s rarely challenged conventional wisdom that pandering to the tough on crime crowd is an effective way to get elected. But with Davis holding both the corrections portfolio and sitting in the deputy leader spot, and Ardern a long-time vocal advocate for a more effective and humane justice system, Labour’s corrections and justice policy platform may have just been blown wide open.

To truly shift the prison population, Labour will need to do better than just develop a lofty goal to reduce reoffending or recidivism, like the National Government did with its 2012 target of reducing reoffending by 25 per cent by 2017. Without any significant policy or legislative change to realise the reduction, National made only a small dent in reoffending rates – even when using questionable statistical tactics – and had to scrap the target in what amounted to an embarrassing admission that were failing to make any real progress.

To put their money where their mouths have been, Labour needs to make it clear up front that it will not proceed with the $1 billion package to house 1,800 more prisoners. Davis in particular has been a vocal opponent and it would be a serious credibility problem if Labour proceeded with the plan in government. Instead, Labour needs to announce a comprehensive package with the clearly stated aim of reducing the prison population.

It will need to look not just at the support offered to current prisoners while they are serving their sentences and after release, but what is fuelling the prison pipeline in the first place. In practical terms, this means that Labour must assess the impact of current sentencing and parole settings, as well as looking at where low-level offending results in a custodial sentence. In the most recent statistics released by the Department of Corrections, 13% of prisoners’ most serious offences related to drugs and anti-social offending, 3.6% to traffic offending and a whopping 20.3% to dishonesty. Over half of the prison population was classified as either low or low-medium risk. Without a doubt, there is a large chunk of the prison population who pose little or no risk to the community, who are being harmed rather than rehabilitated by being in a custodial environment, and who are costing the taxpayer upwards of $90,000 each year – in addition to the $250,000 it costs to build each new bed. There is some low hanging fruit in terms of reducing the prison population, and Labour needs to grab them.

A strong approach on prisons would dovetail with many of Labour’s current priorities. Improved social and community housing, in particular for Māori, and reducing the pressures on the rental market would have a tangible impact on the prison population, with the current explosion in the remand population being driven in part by a lack of secure housing for people seeking bail. This sees people who are of no risk to the community being remanded in prison because a judge cannot be satisfied that they have a home to go to. Labour’s commitment to improving the nation’s mental health would link well to a commitment to reduce the prison population given that incarceration, in and of itself, both drives and exacerbates mental ill health for those who are incarcerated. And with Ardern’s clear focus on children in state care and reducing poverty, Labour can legitimately claim to be focussing on reducing the drivers of crime in its current policy platform. It just needs to be bold enough to position it this way.

Davis and his rise to the role of deputy leader of the Labour Party may yet represent one of the most exciting developments in prison policy in decades. Backed by a leader with a similarly clear vision for a more effective and humane approach to crime and punishment, a seismic shift in corrections policy could come by way of a Labour-Greens government. With an incumbent prime minister who famously labelled prisons as “a moral and fiscal failure” and a minister of corrections desperately seeking options to reduce the prison population, Labour can put forward a radical platform to overhaul the prison system and National will be unable to do much more than nod along in agreement. There is the very real possibility – pinch me now – that this election we could see a rational, evidence-based debate on the way forward for New Zealand’s broken prison system. Let’s do that.

Read more of The Spinoff’s coverage of the suddenly very interesting Election 2017

This content is entirely funded by Simplicity, New Zealand’s only nonprofit fund manager, dedicated to making Kiwis wealthier in retirement. Its fees are the lowest on the market and it is 100% online, ethically invested, and fully transparent. Simplicity also donates 15% of management revenue to charity. So far, Simplicity is saving its 7,500 members $2 million annually. Switching takes two minutes.

The views and opinions expressed above do not reflect those of Simplicity and should not be construed as an endorsement.