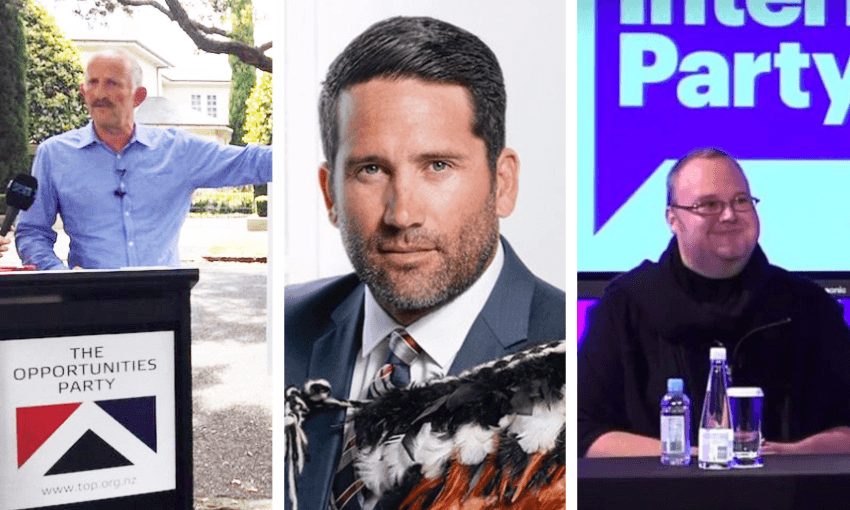

With the demise of The Opportunities Party, the protest vote they garnered will need a new home. But where? Alex Braae assesses the candidates.

Even as the fond memories of TOP’s brief existence fade away, a few defining pictures remain. There’s Gareth Morgan on a billboard, talking about lipstick. There’s Geoff Simmons, chatting away amiably about policy prescriptions that will mostly go over everyone’s head. There’s press secretary Sean Plunket, phoning local website editors.

It’s quite easy to forget that around those totemic figures, there was actually a party. TOP had plenty of candidates, some of whom were quite persuasive. Activists turned out with badges at events. They had money, and a relatively coherent platform. All of that combined to make them the perfect vehicle for the protest vote.

Sometimes the protest vote is driven by a desire to see radical steps taken. Sometimes it’s driven by a general sense that the government needs a good shake. Sometimes it’s just a laugh. The protest vote isn’t so much defined by what policies and parties it groups around, but by people being willing to cast it despite all the signs pointing towards it being a waste. MMP has a brutal threshold for minor parties to clear, and far more than just two realistic options to vote for. But protest voters aren’t interested in picking the lesser of seven evils. They want to vote against that.

Because of that, a lot of different parties fit the bill at different times. Protest votes only make sense in the particular context of their time – the exception of course being the remarkably hardy Legalise Cannabis party. Voters aren’t stupid, and they’ll generally have a pretty realistic understanding of what the post-election landscape will look like. But it’s not the case that protest vote catchers always lose. Back in 2011 New Zealand First came back from the dead, despite spending pretty much the entire election campaign polling under the 5% threshold. But the government was looking almost certain to be National–led, meaning voters from all over the place could then feel more free to cast a safe protest vote.

The fact that the central figures of protest vote catchers are often entirely unsuitable for standard parliamentary practice isn’t a hindrance at all. In fact, it can be an advantage. Some of TOPs voters will have actively liked the fact that their leader was abrasive. It broke with what some see as cosy establishment norms, and upset the people they wanted to see get mad. The same would have been true of many of Hone Harawira’s voters. They didn’t care whether or not he got on with other politicians – he had been sent to Wellington to fight other politicians.

So where will protest voters turn next? Could new political parties form around various prominent individuals and a defining cause? The Sir Geoffrey Palmer Written Constitution party, or the Lance O’Sullivan Please Get Vaccinated party? Or perhaps around broad causes, like becoming a republic, or protecting animal rights. That kind of formation is possible, but still wouldn’t really make any electoral sense. How do you turn that into either 5%, or an electorate?

Then there’s Civic. This is one of the fragments of TOP that split away after the election. It was formed by former candidates Dr Jenny Condie and Jessica Hammond, who both seemed to get heartily sick of Gareth Morgan long before he decided to purge them. They tweet a couple of times a week about open government, which at the very least is a good idea. But they’re not a registered party, and will need to clear some significant hurdles – like getting 500 members, before they’ll be able to be.

There are also the vaguest mutterings of a possible new left wing party, perhaps around the Mana party, perhaps entirely separate. With the Greens in government and having to be disciplined and sensible, there’s clear space out to their left for a new party. Or a new party could form or rise on the far right, in the manner that has happened across Europe – such as AfD in Germany, or Golden Dawn in Greece.

If I had to make a wild prediction about where a brand new party might find any space before 2020, it would be in the area of digital rights, commerce and identity. It’s an area of politics where parliament hasn’t really kept pace with the rest of society, and lives are increasingly defined online. And two and a half years is a long time on the internet – think about the coarse and primitive memes we laughed at in 2015.

Of course, there’s some wreckage that needs to be cleared before an electoral vehicle can park there. The Internet Party were so explosively unpopular with the general public in 2014 that they managed to destroy not one but two parties, and cause blast radius damage to Labour and the Greens. Incredibly, the party stood again in 2017, with an entirely different list. They came in literal last place.

And that puts TOP’s achievements in context. Yes, they failed to make it into parliament, or survive beyond a single election. They also failed to get any real policy wins, and didn’t really make friends or influence people.

They also convinced about 1 out of every 40 voters to choose them. That sounds like a bad ratio, but in relative terms, it’s astonishingly successful. The majority of parties who stand in any given election don’t even come close to cracking a percent. But the people behind TOP genuinely tapped into real concerns, and did remarkably well at capturing the protest vote. It remains to be seen who, if anyone, will be able to repeat that feat next time around.

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.