Research points towards an unconscious, cognitive basis for racism and other forms of discrimination, suggesting that even the super-woke can be secret and subconscious racists, writes Danyl Mclauchlan

I thought about this story a lot over the summer break. It wasn’t one of the huge scandals or rolling controversies from last year, or even one of the looming policy issues (drugs, social media, housing). It was a single cycle, blink-and-you-missed-it feature published in the Herald in October, written by Nicholas Jones, reporting on the findings of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee, which found there was a statistically significant racial gap in the resuscitation and mortality rates of premature babies. White babies were more likely to survive than brown ones.

Is that because of racism? It’s gotta be racism, right? Well, it’s complicated: almost everything in human health is multifactorial, meaning there are multiple causes. Part of the higher rates for Māori perinatal (the period just before or just after birth) mortality is attributed to the higher incidence of Māori women presenting at rural hospitals without specialised neonatal units, which have a lower survival rate for premature births. But one of the key findings is that “inequities by ethnicity are increasingly found in health care both in New Zealand and overseas, and are associated with implicit bias and racism”.

“Implicit bias and racism.” The Herald story focuses on racism, presumably because that’s a concept most of us think we understand, but research into racial inequality is increasingly focused on that first term, implicit bias – it points towards an unconscious, cognitive basis for racism and other forms of discrimination and shows how they exist even in people who overtly reject racist attitudes. Implicit bias, in other words, means that even the super-woke can be secret and subconscious super-racists.

How? Let’s start with Henri Tajfel, a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor and social psychologist. After the war Tajfel decided – for not very mysterious reasons – to study prejudice, group psychology and social identity. How do humans form affiliations to groups, like races or nationalities, and why does that often incite us to demonise other groups? He divided a bunch of undergraduate students into random teams – and told them they’d been randomly selected; none of them knew each other, they’d probably never interact again – and had them perform various tasks like divide resources or judge members of the groups at different activities. The subjects showed a massive preference for their own group and its members even if they knew they’d only been assigned to that group through the toss of a coin.

It’s a finding that’s been replicated many times across many different places and cultures, and it serves as the basis for the Minimal Group Paradigm, describing the innate tendency for humans to affiliate to ingroups on the basis of social identity.

All of us have a host of different, sometimes conflicting social identities crowding around inside our minds. I’m white, a male, middle-aged, married, a New Zealander, a father, middle-class, a writer, and so on. We switch between which affiliation feels most salient given the circumstances, primarily identifying with whichever ingroup awards us the higher status. Politicians and other actors are increasingly adept at activating these different identities, manipulating us into defining ourselves in a way that strengthens our connection to them and makes us believe they personally champion our ingroup – which is always the victim of some sinister outgroup.

We think of outgroup discrimination – especially around race – as something very obvious and aggressive (“Go back to where you came from”), or as an ideological justification for that behaviour (“This is our country!” “The white race is the genetically superior master race!”) and there’s often controversy whenever people talk or behave like that, because, well, it’s racist. But what the research into implicit bias shows is that even without that kind of behaviour and rhetoric, even among populations that strongly disapprove of racism you still see ingroup favouritism and outgroup discrimination.

The easiest way to see how this works is to head over to Harvard University’s Project Implicit site and take one of their Implicit Association Tests. There’s a variety of options but we’re talking about race, so take the race one. What you’ll probably find is that you have trouble associating positive words with other-race photos and negative words with same-race faces.

What that’s revealing, if you didn’t bother to take the test or read any of the explanatory notes, is your brain’s unconscious bias. Most of us have a naive belief that our conscious awareness is synonymous with our brain, that the brain is a ship and the self is the captain: it knows what’s going on and makes the rational decisions. But the reality of human cognition is nothing like that. Our conscious minds are more like vain, incompetent ministers overseeing an opaque bureaucracy. The brain takes in more information and makes many more judgements than the conscious self is aware of: instead of making rational, logical choices our rational minds spend much of their time fabricating post-hoc justifications for intuitive unconscious judgements – like our attitudes towards other humans.

You sometimes hear people assert their progressive credentials by claiming they “don’t see race” or “just treat everyone equally”. IATs show us that everyone sees race; no one treats everyone equally, and, crucially, most people see race in a subjective, non-neutral way. We make judgements about people based on race (and attractiveness, and gender, and weight, and perceived socioeconomic status and other visual cues) without realising we’re doing so. And then we make decisions based on those judgements: a surgeon in a NICU ward resuscitates a same-race infant because she looks a little like her daughter; a microbiologist at the end of a long day leaves a blood test for an other-race infant to the next shift because their name is hard to spell. Over time those decisions aggregate, and in domains in which tiny differences have life and death consequences, they aggregate to life or death outcomes for different races.

IAT’s and their findings are extremely controversial. There’s a Wikipedia section litigating the controversy here, and some of the criticisms are valid disputes over methodology and some are ideologically motivated: conservatives dislike IATs because they prefer to think that racial inequality is motivated by cultural or genetic differences (most of the discussion about race and IQ is attached to this trope). The far left prefers to see racism purely as a product of ideology; naturally the key to defeating it is for everyone to adopt their ingroup’s ideological beliefs. But implicit bias is an increasingly influential idea in the social sciences because it is both measurable and parsimonious: it explains a huge range of behaviours and outcomes that otherwise defy explanation.

How many of our successes and failures in life are determined by people making judgements about us? Educational assessments; clinical diagnostics; job appointments; promotions; who gets a mortgage; who gets arrested; who gets a prison sentence. How much of the inequality in racial outcomes is determined by the accumulated weight of countless unconscious decisions made by members of the racial majority who dominate those institutions – partly for historical reasons but also because there’s just more of us – over the course of our lives? The disparity in perinatal fatalities suggests it’s significant and that it starts before birth and – given the disproportion in life expectancy for different ethnicities – continues until death, like a dilute poison in the water supply.

Most people score differently on IATs if they take them recurrently. (The most notorious finding in the US studies: white women have more negative attitudes towards African-American men when they’re ovulating.) It’s possible to override implicit associations: the slow, resource hungry, rational parts of our brain can rumble into life and revise our intuitions – but the more stress we’re under the more likely we are to default to implicit judgements.

Essentialist thinking – attributing some essential quality or trait to all members of a group – “Māori are violent; Asians can’t drive; women are bad at maths” – increases negative bias. Seeing people as individuals rather than members of an outgroup reduces negative bias. Seeing them as members of the same ingroup (“We’re all New Zealanders!”) massively reduces negative bias.

But the most effective tool is to be aware of our own bias and understand that our judgements about members of outgroups aren’t rational and, summed across institutions and lifetimes, have devastating consequences. A lot of social justice activists focus on privilege shaming: calling people out for their perceived membership of privileged ingroups, and I think that awareness is what they’re trying to accomplish. But implicit bias takes many forms other than race and gender – there are robust IATs findings for age; sexuality; disability; weight; religion. Attractive people enjoy massive positive bias; so do people who are intelligent, especially if it’s verbal or social intelligence; so do people with high socioeconomic status and/or social capital – like a tertiary degree. We’re mostly blind to our own privilege but resentful of that of our perceived rivals, so privilege debates can spiral down into macabre status contests between factions of elites about which of them is the most oppressed.

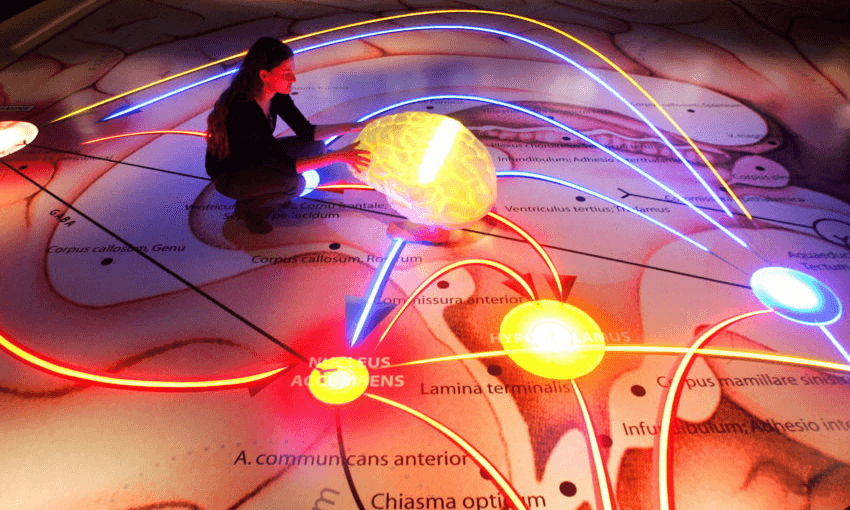

I find it depressingly easy to get invested in these conflicts. I spent a lot more time last year thinking about whether Don Brash should have been deplatformed, or who should march in the Pride Parade and what clothes they should be allowed to wear, than I did thinking about perinatal infant mortality. I’ll probably do the same this year: these conflicts are ubiquitous in the media and they light up the ingroup-outgroup circuitry of my brain like an ECG machine.

And they’re also, I suspect, a convenient distraction: an entertaining way to forget that inequality and discrimination afflict the most powerless – those who have no voice in politics or the media, by definition – the most profoundly. That the choices we make as we go about our day can echo through lives we’re only peripherally aware of; that we can make things better for those who have the least in our society at very little cost to ourselves, just by being aware that we can; and to guard against our lack of awareness because it is the not knowing, the indifference, that makes things worse.