Beyond the direct and practical implications, more significant for the eventual outcome is the effect on the electorate’s psyche, writes Ben Thomas.

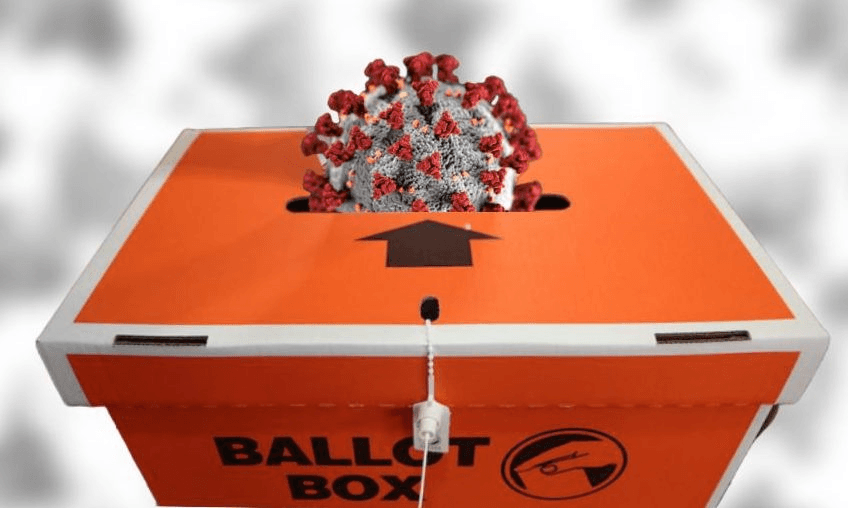

It’s tempting to reach for easy metaphors with the re-emergence of Covid-19 just weeks before the election: a horror villain rising from the dead; a restless spirit summoned to again haunt the dreams of New Zealanders. Just when we thought it was safe to go back into the supermarket. Et cetera, et cetera.

Jacinda Ardern, as Labour leader, announced on Saturday that this would be a “Covid election”. What she meant of course was a post-Covid election; a campaign basking in (deserved) public acclaim of her government’s success in squashing the pandemic in New Zealand, and the encouraging (if not wholly reliable) economic figures last week.

Despite job losses and business failures, albeit far fewer than expected, after 100 days without community transmission, the lockdown seemed more like a hundred years ago. The Covid tracing app was living, but not alive

Gerry Brownlee’s borderline paranoid questioning of the government’s timing of announcements about future rules on mask wearing could sound alarmingly prescient. They are of course not.

Statistically a second outbreak was probably inevitable at some point.

There are questions around the border however. It is unlikely given the nature of the virus’s spread that it has been lingering undetected in Auckland for over 100 days with no larger outbreak. The suspicion is that, as in Victoria, the cases originate from the managed isolation facilities or the border.

Management of the border has been unquestionably more rigorous since Megan Woods replaced David Clark in that role.

But some of these criticisms will be reasonable – and will suggest that the new cases were foreseeable. Economist Eric Crampton has been calling for regular testing of border staff for weeks. Last Tuesday the Director-General of Health said that border staff were being tested every two to three weeks – a full cycle of the virus, to use the terminology from lockdown.

Sources told Newshub that some bus drivers, carrying passengers from overseas for up to three hours at a time, had not been tested at all. It’s probably no surprise that direct links to the new cases have not yet been found.

Other criticisms may feel fair, even if they are not: if the borders are not secure, why are consultants for a NZ First pork barrel sop to the racing industry given priority over returning New Zealanders? Will we let just anyone in?

Community transmission was inevitable at some point. The fact that it has not yet been traced points to a weakness in testing either at the border or during the period when surveillance testing dropped to mere hundreds of swabs a day, well below necessary levels.

These are real issues that the government should be interrogated on, and addressed.

Conspiracy theories are not. Whoever wins the election – and the re-emergence of the virus must suggest common wisdom on the outcome is out the window for now – will have to govern in the Covid world. That’s a world that needs clear thinking and trusted institutions, whichever party holds their reins.

National must resist lurching fully into the paranoid style its leadership has flirted with in recent days.

Deputy leader Gerry Brownlee has been asking questions about the government’s efforts to get the public warmed up for exactly this kind of situation, with revised advice on masks. It seems prescient, as hindsight often does. But the onus is, perhaps perversely, on National to put up or shut up.

If Brownlee has reasons to doubt the timeline given by the prime minister, he should produce them, or make clear the basis for his suspicions so the media can pursue it further. Otherwise, he and Collins should stick to the facts as known: innuendo has no place in disaster management.

As far as the election goes, there are now logistical issues. National’s campaign launch in Auckland this weekend is unlikely to proceed. Candidates contesting a third of the country’s electorates will be unable to doorknock or hold meetings for at least three of the 24 days before early voting begins.

Probably more significant for the eventual outcome is the effect on the electorate’s psyche.

There has been a puncturing of complacency. Despite the rigours of lockdown, a comfortable amnesia had set in in large parts of the electorate not directly affected by job losses or business closures.

The prime minister reiterated that New Zealanders have already done what was needed to eliminate the virus. That’s true. But the announcement brings home the uncomfortable truth that there is no such thing as a Fortress New Zealand. We may be in and out of lockdown whoever is in government.

Labour, sensibly, planned to fight the “Covid election” on its record, the successful victory against the virus. Now, the electorate may think more about what the future looks like, if we accept that it must be different from what we’ve known.

Politicians, used to the endless grind of trying to fix intractable issues like poverty, crime, business growth and race relations year after year, and term after term, may understand the new normal better than most: that the most apt metaphor for where we are now comes not from monster movies or slasher horrors. A better image comes from Bojack Horseman, describing the imaginary sitcom Horsing Around: “there’s never a happy ending, because there’s always more show.”