If we want to reduce the harm done by social media in any meaningful and sustainable way, we have to address the root causes, writes Marianne Elliott

Read the full text of the Christchurch Call here

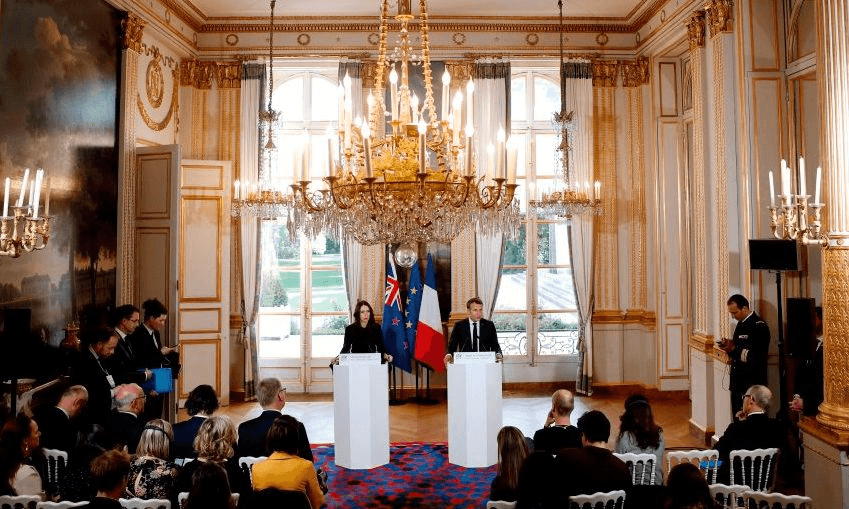

In Paris this morning Jacinda Ardern announced the successful agreement of the Christchurch Call, a voluntary pledge by governments and tech companies to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online.

While the tech companies are emphasising that this agreement builds on their own previous work, including the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism formed by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube in 2017, the New Zealand government will, justifiably, want to emphasise that unprecedented nature of this agreement. The pledge was signed by eight tech companies, including Facebook, Twitter and Google, and 17 nation states. Not, however, by the United States, in keeping with its poor track record on multilateral efforts to protect human rights.

New Zealand’s influence can be seen in the framing of the pledge within a commitment to a “free, open and secure internet”, in the clear focus on the human harm done in Christchurch, and in the explicit insistence that a free and open internet must be protected “without compromising human rights and fundamental freedoms”. It’s likely some human rights experts and members of New Zealand’s Muslim community may question the choice to give special mention to freedom of expression here, and not the many other fundamental rights relevant to this conversation, including, perhaps most importantly the right to life, liberty and security of person.

The Christchurch Call, and Facebook’s own pre-emptive announcement of a new “one strike” ban on live-streaming, has shown that under the right kind of collective pressure from citizens and governments, the tech giants will act. This is an important counter to a kind of learned helplessness in which experts, officials and elected representatives have thrown up their arms and said “these companies are too big to be reined in”. Which, besides being a clear dereliction of democratic responsibility, and of sovereignty, became morally and politically impossible to sustain after the Christchurch mosque attacks.

So, we have action, and an agreement which, despite focusing very narrowly on the most extreme kinds of violent and terrorist content online, does acknowledge some of the broader contributing factors to the spread of that content. Including a defiant lack of transparency and accountability from the CEOs of these tech giants, who control not only the means by which billions of people communicate with each other every day, but also the distribution of news and current affairs to the majority of people in many countries. This handful of mostly Silicon Valley-based men control significant pieces of our democratic infrastructure, yet have refused to accept the kind of accountability and responsibility which has been expected of comparable companies in the past, including the mainstream media.

In the Christchurch Call, tech companies commit to provide greater transparency in the setting of community standards, and to enforce those standards “in a manner consistent with human rights and fundamental freedoms”. They have also committed to “implement regular and transparent public reporting, in a way that is measurable and supported by clear methodology”, but only on the specific matter of the “the quantity and nature of terrorist and violent extremist content being detected and removed”.

It’s a start, for sure. But because it excludes all other forms of harmful content, it won’t go far in helping governments, researchers or civil society understand, for example, how the algorithms that drive these platforms may be contributing to extremism and radicalisation.

What the Christchurch Call shows is that these companies will act, under pressure, but also that they will do the least they possibly can. Wherever possible, they’ll try to convince governments that initiatives they already had in play – like Facebook’s “one strike ban” or the “Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism” – are adequate.

I don’t want to minimise the significance of the Christchurch Call. It is an important step in the right direction, and it’s very likely that the prime minister was correct in her assessment that the only way to get broad agreement on this text was by narrowing its focus and making it voluntary. But it is very important that this pledge is seen as only a small part of the solution to the larger problem.

Over the past year, together with Dr Jess Berentson-Shaw and Dr Kathleen Kuehn, with help from Dr Leon Salter and Ella Brownlie and funding from the New Zealand Law Foundation, I’ve been researching the impact of digital media on democracy here in New Zealand. Our research found that the harm done to people and democracy by digital media is driven not only by the behaviour of a few bad actors using these platforms, but by the unintended effects of the underlying business model of the attention economy, the monopolistic power of a handful of companies and the opaqueness of their practices.

In particular, the algorithms that are the engines of these platforms are using an unprecedented amount of data to control the flow of information to citizens, without any transparency or accountability around how they work and the harm they may be doing to democracy. If we want to reduce the harm done by social media in any meaningful and sustainable way, we have to address those root causes.

Trying to eliminate the spread of terror online without addressing the underlying drivers of that spread is like trying to stop ocean acidification without addressing the drivers of climate change. There may be some partial and temporary reductions in superficial symptoms to be found, but the underlying problem will remain, and the symptoms will quickly return.

If the widespread harmful effects of digital media on our democracy is like climate change, then Ardern’s Christchurch Call is like a voluntary agreement between a handful of (powerful) governments and some of the biggest fossil fuel companies in the world to do what they can to staunch the worst oil spill we’ve seen in history.

In other words, it is urgent, important and historic, but on its own it may not prevent the worst happening again, nor will it slow down the myriad other symptoms of the underlying problem. In our research on the harm digital media does to our democracy, we found that despite the potential of digital media to create new opportunities for democratic participation, and some signs that potential was being realised in certain circumstances, the overall trend was bad. Harmful effects include the silencing impact of hatred online, the polarising effect of algorithms designed to give us more of what we have already shown a preference for, and the tendency of some algorithms to feed people increasingly extreme content in their endless drive to grab and hold your attention.

In the Christchurch Call pledge, social media companies pledge to “review how algorithms may drive users to terrorist and violent extremist content in order to design intervention points and redirect users”. This is a voluntary pledge to review their own algorithms. Given the track record of these companies when the harmful effects of their algorithms have been drawn to their attention, it would be an optimistic observer who expected this to produce meaningful change. But it is a first step, and one which gives governments the starting point for future conversations about independent review of these algorithms by trusted third party bodies, if the platforms fail to deliver real change through this pledge.

Our research found other significant democratic harms from digital media including the impact on traditional advertising funding for public interest journalism. Combined with the ease with which misinformation and disinformation can be distributed and amplified through digital media, this has been shown to undermine shared democratic culture, including how well-informed citizens are on matters of public interest. We also found evidence that New Zealand’s political, government and electoral systems could be at risk of being digitally manipulated by hostile actors, and little evidence that our government is equipped to respond to such an attack. This will come as no surprise to the cybersecurity community.

What all of this added up to was a significant corrosive effect on democracy – not only globally but here in New Zealand – and a clear duty to act on the part of governments.

Since the Christchurch mosque attack, Ardern has taken that duty up, and begun a process which, while narrowly focused and voluntary for now, could provide a starting point for a wider ongoing effort to tackle more of the underlying issues at play. For that to be successful it will need:

- Clear timeframes within which governments and tech companies will act on the commitments they have made in Paris;

- An independent process for reviewing both action on those commitments and the impacts they are having on the spread of extremist content (noting that the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism is not, in its current state, independent);

- Incentives for action for the tech companies;

- A commitment from governments and tech companies to work together and with civil society on the wider aspects of harm to democracy from digital media and the underlying drivers of those harms; and

- Meaningful participation by credible representatives of civil society who have access to the data they need to offer an independent perspective on the claims made by governments and corporations as to their actions.

Marianne Elliott is a researcher and human rights lawyer. Dr Jess Berentson-Shaw is a researcher and public policy analyst. Together they founded The Workshop, a research and policy collaborative. Their Law Foundation funded research on the impacts of digital media on democracy can be found here.