Peter Dunne was bloody good at parliamentary business. But building a sustainable political party is about building a political movement, writes Alex Braae

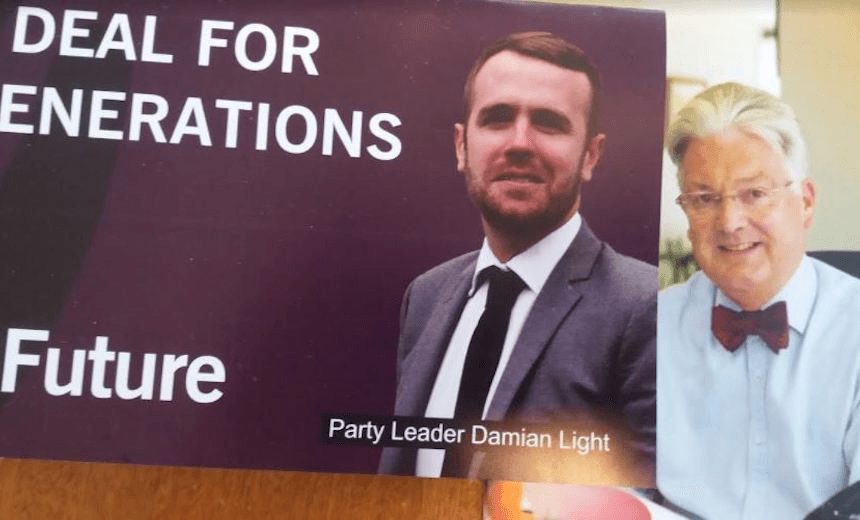

The purple corflute was stacked up next to the wall, slogan side up. In the courtyard of a cottage in the heart of Botany, enclosed by a fence, they were invisible to the public. It was about a week after the election, and the country was fixated on the special votes, and whether they’d tip the balance of power. United Future’s leader, Damian Light, was figuring out what to do with the remains of his party.

The decision to call it a day for United Future was this week announced, but it was already in the air then. Whether to disband, whether to rebrand, whether to emulate former MP Judy Turner and run for council seats as independents, whether to fight on. Only one of the options – to disband – ever made any sense. I spent a lot of time during the campaign thinking about United Future. I interviewed a lot of people who had connections with it, or might have some insight into their inner workings. And as it turned out, there wasn’t much in the way of inner workings to be divined. Below the executive level, the party barely existed.

Damian Light was shouldering a heavy load to keep the party going long before he was the leader. He was the party president, which in any party is no small administrative task. He was also the acting secretary, pending the appointment of someone else who might have volunteered. That wasn’t happening in a hurry. Peter Dunne, whose surprise exit led to Light becoming leader, made a telling comment to me in an interview before the election. He said Light would make a good parliamentarian, in part “because he has the stamina for it.” Light said there was a small core of people who shouldered some of the burden, too. But in the meeting where the decision was taken to disband, only a few members showed up, and, in Light’s words, “most of the board.” Some of the party’s key people, it seems, didn’t even turn up to the funeral.

Former UF member and politics blogger Pete George told me that when there was a membership crisis, and the party was deregistered by the Electoral Commission, the publicity led to an influx of new members. In a line I heard repeated dozens of times from voters during the campaign, they “thought the party had some good ideas.” But almost none of the people who said that intended to vote for United Future, let alone get actively involved. That disparity, with a high proportion of passive members, simply isn’t sustainable for any party.

One lesson that could be taken from the fate of United Future is that centrist parties no longer have a place in New Zealand. And it’s true, in a really limited sense, but it’s also the wrong question to ask. The last government was decided by a reasonably centrist minor party choosing between two reasonably centrist major parties. United Future’s policies are all broadly palatable to the vast majority of voters. Theoretically most voters are roughly in the centre. So what gives?

Throughout the campaign Damian Light kept repeating a line about how United Future had never been out of parliament, and so predicting the future was difficult. The inverse of that is that they had only ever been an explicitly parliamentary party. The very first incarnation was a bipartisan group of waka-jumpers, who thought they could hold the balance of power under MMP between Labour and National. None survived except Dunne. For the next 21 years he used his hard won electorate seat to lure in outside groups with energy, activists and possible vote banks. Christians, outdoors types, a lobby group attempting to overturn the ban on smoking in bars, they all came, and most of them left.

It was vitally important for Peter Dunne to be able to bring these groups into the party. Even in an age of slick, professionalised political messaging, where party executive branches increasingly tend to dominate members and activists, movements matter. Building up a political movement requires many hands. It’s slow, boring, and crucial for a party to survive the departure of dominant figures. It’s how the Greens survived the death of Rod Donald, and the political immolation of Metiria Turei. United Future never had that. There was no passionate populism to keep activists going on rainy Sunday mornings at the markets. There was only the promise of tinkered improvements in select committees, or ministerial competency, or a stern question asked in the House. Making parliament work better will never be enough to sustain a party by itself.

The policy that became United Future’s signature issue – radical drug law reform – failed to capture the imagination of campaigners. Rather than being framed as a policy of liberation, of an end to the manifestly unjust drug war, United Future’s efforts were legalistic and procedural. The Psychoactive Substances Act was lauded by the Drug Foundation as world leading. It was a fantastic piece of governance and administration, and yet at the next election Legalise Cannabis got twice as many votes as United Future. That sort of politics earns points with experts, the Press Gallery and other politicians, and Peter Dunne was incredibly skilled in the business of parliament. It’s probably no coincidence that Dunne repeatedly won Ohariu, an electorate with a high proportion of public servants living in it.

The proof of this all came when Damian Light burned bright. His rapid delivery and good looks won over Twitter during the TVNZ minor party leaders’ debate. He went viral. But there’s a huge difference between going viral in a media sense – lots of retweets, TV news articles and so on – and going viral in a political sense. A good comparison would be Chlöe Swarbrick, who accomplished both. She managed to pull in thousands of votes for the Auckland mayoralty because not only did she have the media spotlight, she tapped into a deeper and broader movement of young people who were fed up with how the city was being run. By contrast, Damian Light was a meme. And nobody votes for a meme.

His efforts this year never had a chance, because there was no movement for him to lead. Of course, some might compare Light’s debate success to Peter Dunne’s in 2002, when Dunne tamed the worm and cracked five percent. The difference there was that United Future had recently incorporated social conservatives like Gordon Copeland, and National was tanking. The party had a common sense constituency to champion.

Damian Light was, in all of my interactions with him, a really nice guy. In fact in seemingly every interaction anyone, anywhere had with him, he was a really nice guy. And that niceness rubbed off on politicians around him, too – pointedly nobody really attacked him directly in the Minor Party debate. What would be the point? You’d just look like an ogre, picking on the really nice guy the audience had just met.

After the election, the party’s No 2, Ben Rickard, told me that a clear-out might be needed of the United Future membership. That because not everyone who had joined and hung around from the various amalgamations and mergers would get behind a liberal centrist vision, they should probably go. The option seemingly wasn’t discussed at the final meeting, and one probable reason why is that any clear-out would require replacements. That was never going to happen, because a parliament focused electoral vehicle without electoral prospects is nothing.

After the election was over, Damian Light mowed his lawn. The suburban neighbours were apparently delighted that he could now get around to it. He’s got a lot of time now to consider his options, and he says he’s not done with politics yet. Any party that took him on would do well to look beyond the telegenic meme, and see instead all the work he did before he was leader. People like him – the ones who actually run the party and campaign tirelessly – they’re the people that get MPs elected. He was one of the few who passionately believed in United Future’s purpose, and made that passion count. With a few more like him, the party might still be alive today.

Listen to Alex Braae’s audio series on United Future below …