The Todd Barclay affair has prompted many memory lapses, but perhaps none as powerful as Prime Minister Bill English’s now-forgotten objections to cover-ups and deceit. Branko Marcetic looks back to 2002, when Helen Clark’s Paintergate and Corngate scandals were making the news – and Bill English was making hay.

“Today we see the real story – at the heart of the Government a sordid tale of lies, deceit and convenient forgetfulness … The Prime Minister of New Zealand of course knows nothing about it…”

“I have never seen such slithery dishonesty from the leader of our country.”

“This behaviour from someone in such high office is unacceptable.”

These are of course just three more examples of opposition MPs piling on Prime Minister Bill English in the wake of the rapidly unfolding Todd Barclay scandal. Or are they?

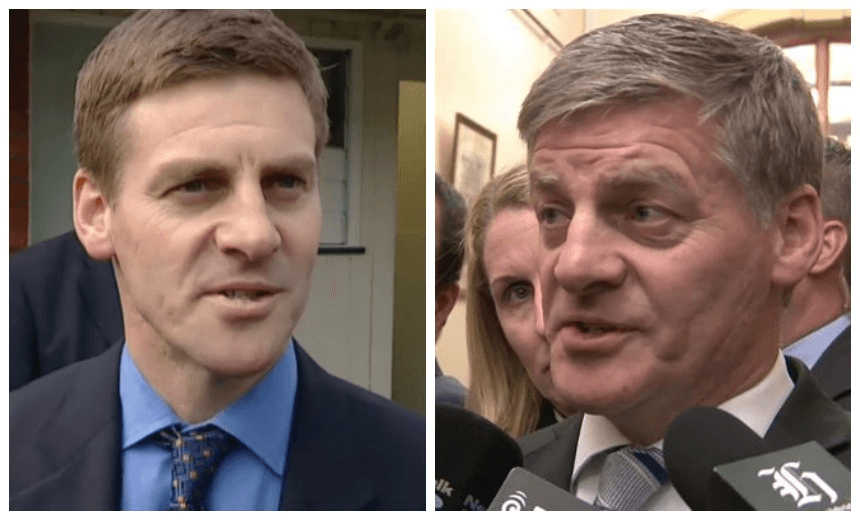

The statements did come from MPs – a single one, to be exact. But it’s not Andrew Little in 2017. This was Bill English in 2002, criticising Helen Clark for her conduct in the so-called “paintergate” scandal.

Fifteen years ago, Bill English was leader of the opposition and head of a National Party which was in straits slightly more dire than Labour has been in during its wilderness years under John Key, and was (at one point, quite literally) fighting for its life. Helen Clark was leading a then-popular Labour government that was prone to various scandals, often labelled with the dreaded “-gate” suffix. They ranged from the quite serious (“corngate”; the Taito Phillip Field corruption affair) to the somewhat goofy (“paintergate”; “speedgate”).

“Paintergate,” as it unfortunately came to be known, concerned Clark’s signing her name on a series of paintings painted by other people that were subsequently sold at charity auctions. Clark’s signature on the paintings gave the impression that she had been the artist behind the works, thus embroiling her in charges of fraud and forgery (one of the paintings, for instance, had been bought for $1,000, a sum the buyer probably wouldn’t have spent had they known it was the handiwork of someone who wasn’t the head of the fifth Labour government).

English, whose National party was polling close to a 10-year low at the time, seized on the incident to hammer the message that Clark’s government was an ethical black hole that was overrun with corruption. And to be fair, there was much in Clark’s response to the controversy that merited criticism, from having the painting destroyed to her refusal to answer the police’s questions as part of their inquiry.

Unfortunately, English’s public statements at the time don’t look too good now, when he appears to be guilty of something much more serious than signing a painting: keeping mum for around 18 months about a National MP’s potentially criminal actions in order to protect the party’s majority in Parliament – even as the MP repeatedly gave false statements in public about the matter, and suffering a timely memory lapse when confronted with the story.

Now caught in a political scandal of his own, English’s initial response was to play the tried and true card of not being able to remember whether or not he’d been told by Todd Barclay that he had secretly recorded his former electorate secretary, telling reporters, “I can’t tell you in a conversation two and a half years ago,” and that “I can’t recall exactly what was said by whom, when.” He also appeared to play down the affair, saying on Tuesday morning that it was “still unclear what, if anything, happened,” and continuing to refer to the matter as an “employment dispute.”

It’s a stark change from the English of 2002, who did not tolerate similarly shifty behaviour from Clark, who was likewise forgetful about the details of actions she had carried out roughly the same number of years before.

At the party’s 2002 National Conference in Wellington, English declared Clark’s conduct regarding the signing of the paintings “a sordid tale of lies, deceit and convenient forgetfulness.” “It’s only the people she works with every day who were involved,” he said sarcastically, regarding Clark’s sudden bout of forgetfulness.

English lambasted Clark’s “slithery dishonesty,” going on to describe her behavior as “unacceptable,” “slippery,” a “disgrace” and a “cover-up.” The current circumstances, with his own opponents accusing him and the party of covering up Barclay’s actions, must leave him with a case of deja vu.

English made clear at the time that just by itself, the scandal was a permanent black mark on Clark’s future trustworthiness.

“Who can now trust her on anything she says?” he asked. “New Zealand deserves better than this and under my leadership that is what this country will get.”

While the matter was determined by the police to be a case of prima facie forgery (though not fraud), the police also noted that it was largely an issue of “carelessness or indifference” and didn’t recommend prosecution. The public largely felt the same, viewing the whole controversy as largely trivial.

And in fact, English at the time acknowledged the scandal’s trivial nature. But, he had stressed, this wasn’t the point.

The New Plymouth Daily News reported at the time that English had told the party that it was “a relatively minor matter,” but “what was of concern was the conduct of Miss [sic] Clark and her staff after the matter became public.”

“This is no longer just a case about the prime minister signing paintings she did not create, but about Helen Clark’s honesty and integrity,” he said in a press release.

English took much the same tack with the “corngate” affair, sparked by Nicky Hager’s Seeds of Mistrust, which alleged that a crop of sweetcorn that had been grown and eaten in New Zealand in 2000 had been genetically engineered, and subsequently covered up. National of course wasn’t concerned about GE food; what the episode did show, English stressed, was the government’s reliance on lies and deception.

“The half-truths and the manipulations are what hold this Labour Government together,” he said at the time. “That is how it is run from the top. Each one of these investigations, half-stories, forgetfulnesses, and ‘Clarkisms’ are just little snapshots that the public gets of the way this government and this prime minister do their business.”

The episode showed a “pattern of calculated deceit,” he said. As reported by Palmerston North’s Evening Standard, he told voters in the town that Clark’s “leadership style had become a ‘significant issue’” as a result of both -gates: “She’s not handling the pressure too well.”

The Bill English of 2017, on the other hand, seems to disagree. He told reporters yesterday that with Barclay having decided to stand down, “we can get back to focusing on the issues that matter, rather than internal issues.” Far from the crusading, righteous English of 2002, he seems relaxed about the whole affair, telling the press that “these sorts of issues arise commonly in politics.”

One could argue that whatever English’s missteps in handling the affair after it was revealed to him, the buck ultimately stops at the person responsible. It was Barclay, after all, who had done something illegal, not his leader. When asked if Barclay had misled the media, the prime minister seemed to wash his hands of responsibility, saying, “You’ll have to ask him,” and denying that it was up to him to force Barclay to co-operate with police.

This is a proposition that the Bill English of 2002 would vigorously disagree with.

In 2006, no longer the leader of the opposition, but continuing to serve an attack dog role for National, English sunk his teeth into the Taito Phillip Field scandal, where it came out that Field, a longtime Labour MP, had Thai tradesmen do renovations on his properties in exchange for giving them immigration assistance. Speaking about the nearly $500,000 Ingram report produced on the controversy, English said that its “most important statement” was the one that stated: “The Prime Minister is the ultimate arbiter of the ethical conduct and behaviour of her ministers.”

“That is, and will always be, the case,” English added.

While Barclay is not a minister, one would think this would still be the case when the MP in question has been described as viewing the prime minister as “his guide, sponsor, family friend, neighbour and mentor throughout the entire political process.”

English had made the same point three years earlier, this time regarding a misleading statement the then-CEO of New Zealand Post had given to the Finance and Expenditure Committee in 2001. English spoke in parliament about the report due to “my concern about the culture of dishonesty that now suffuses public agencies in New Zealand – and it starts from the top of the government.”

“We have a culture in the government where half-truths, evasions, and straight-out lies have become acceptable,” he said. He further complained that “no one owns up to the fact of doing something wrong” anymore, something he called a “Helenism,” and charged that what he believed was the NZ Post CEO’s lie was a direct outgrowth of Clark’s dissembling during her scandals – “I don’t recollect. I wasn’t there. It’s not my responsibility,” as English described it at the time.

“Of course the tone set by those at the top of the government influences the civil service and public bodies,” he said.

And what about those faceless government underlings trapped between their principles and doing the bidding of their superiors? Turns out Bill English ca. 2003 also had some choice words of wisdom for them:

“There is no obligation to compromise one’s integrity or one’s honesty in order to help one’s political masters.”

So it turns out the most damning indictment of English’s role in the Barclay scandal today hasn’t come from the opposition. It came from a younger, fresher-faced, less cynical Bill English, who appeared to still believe in the primacy of ideals like truth, accountability and integrity.

English should count himself lucky he hasn’t got that guy on his case now – he was positively relentless.

This content is brought to you by LifeDirect by Trade Me, where you’ll find all the top NZ insurers so you can compare deals and buy insurance then and there. You’ll also get 20% cashback when you take a life insurance policy out, so you can spend more time enjoying life and less time worrying about the things that can get in the way.

This election year, support The Spinoff Politics by using LifeDirect for your insurance. See lifedirect.co.nz/life-insurance